While perusing Spiegel’s superb collection of the best news photos from this past year, this moment of terror arrested my attention:

AP/The Sunday Indian

This adult leopard wandered into a town in northern India and went on a rampage. Fortunately, the fellow here being scalped survived. I do not know whether his scalp was reattached.

It just so happens that last night I was reading George Bird Grinnell’s The Fighting Cheyennes (1915), in which he recounts an 1867 Cheyenne raid on the railroad near North Platte, Nebraska. After the train was derailed (the only successful instance of this), the few survivors fled on foot but were soon caught by the mounted Cheyennes. One of the survivors, William Thompson, was shot and then scalped. But Thompson didn’t die. He picked up his discarded scalp and carried it back to Omaha, where a doctor unsuccessfully attempted to reattach it. After touring Europe with his locks (and presumably making a nice living by telling the tale), he donated it to an Omaha museum, where it can still be seen:

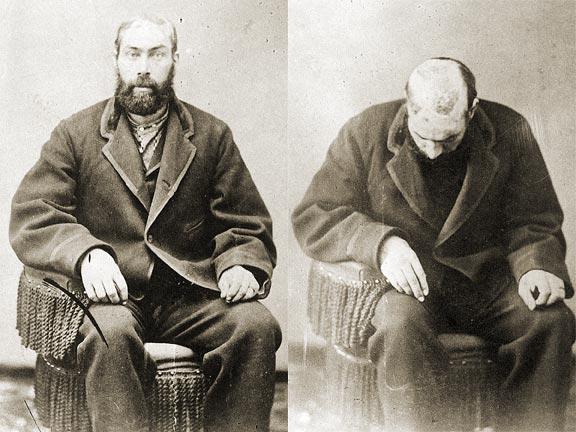

Thompson sure had some pretty golden locks! This is Thompson in later years sans scalp:

As might be expected, scalping meant different things to different tribes. In Coup and Scalp Among the Plains Indians (open), Grinnell asserts that in the latter half of the 1800s scalping had lost much of its spiritual significance. But in earlier times, a fair amount of battlefield ritual surrounded scalping and was followed by dancing back at camp. Among the Cheyenne, a special group of people was responsible for the dance:

These old time scalp dances were directed by a little group of men called ‘‘halfmen-halfwomen” [berdache] who usually dressed as old men. Of these halfmen-halfwomen there were at that time five. They were men, but had taken up the ways of women. Their voices sounded between the voice of a man and that of a woman. They were very popular and especial favorites of young people, those who were married as well as those young men and young women who were not married, for they were noted matchmakers. If a man wanted to get a girl to run away with him and could get one of these people to help him, he seldom failed. When a young man wanted to send gifts for a young woman, one of these halfmen-halfwomen was sent to the girl’s relatives to do the talking in making the marriage.

This is an odd concatenation to say the least. It is the sort of thing that would have gotten Clifford Geertz’s symbolic and interpretive juices really flowing.

The Pawnee, for their part, took scalps much more seriously. In Powers of the Heavens Shall Eat My Smoke — The Significance of Scalping in Pawnee Warfare (open), Mark van de Logt explains:

Pawnee oral tradition shows that scalping was an ancient tradition. It was ingrained in Pawnee culture. Scalps were much more than mere “trophies” and symbols of prowess. They represented the “essence” or “life-power” of an individual, but not the soul. Pawnee men went to war to obtain or restore spiritual power and thus to raise their status within the tribe. They also took scalps to ensure the vitality and survival of the Pawnee people. The quest for scalps, therefore, could be a cause for war. When going on an expedition in search of scalps, the Pawnees changed their tactics accordingly. They took scalps and other body parts of their victims. Although these body parts shared the same supernatural qualities as head scalps, the latter were more common. The Pawnees also took scalps to avenge the loss of a relative or loved one, and presented them to people who were in mourning. In the process they symbolically restored power to the tribe. The Pawnees sacrificed scalps to thank the supernatural powers for favoring them in battle, as well as to renew and strengthen the covenant with the sacred powers. Scalping, then, was not merely an act of war; it was an act of great cultural significance.

Whatever scalps may have ritually signified to the Pawnee, it is abundantly clear that taking scalps made socioeconomic sense. As Plains tribes were being compressed on all sides by colonizers and buffalo herds dwindled, competition for territory and hunting grounds became intense. Scalps were but symbols of the underlying competition.