Reading unpublished and unfinished works by an author always makes me feel slightly uncomfortable, as if I’ve been rummaging around amidst their private correspondence or prised open their locked diary. If they hadn’t wanted to finish it, didn’t think it was good enough to be published, and didn’t put it out there in the world to be read, is it right for us to go against their wishes and introduce it into the public domain? I felt so uncomfortable about the troubling circumstances of Go Tell a Watchman‘s publication a couple of years ago that I couldn’t read it, despite my curiosity. Therefore, though I love Jane Austen and would be perfectly happy to only read her writing for the rest of my life, I have never delved into her fragments or juvenilia. However, the advertising of the new BBC adaptation of Sanditon piqued my interest, and then Oxford University Press sent me a copy to review, so, rather guiltily, I allowed my curiosity to overcome my morals and read the remaining fragments of what would have been, if she had survived and decided to continue with it, Jane Austen’s seventh novel.

First and foremost it must be understood that it truly is a fragment; a mere seventy or so pages, made up of twelve short chapters. Plenty of characters are introduced, but very little plot happens, though much is hinted at, and a seasoned Austenite could hazard a guess at the plans she had for her characters, all of whom possess comfortably familiar traits. This is what makes Sanditon a very interesting reading experience, for the ending is abrupt, on the cusp of the arrival of a new character who, if Austen was planning on staying true to form, would undoubtedly have thrown the lives of the inhabitants of Sanditon into some disarray. What would this story have become? What would Austen have wanted to tell us through the world she only begins to create? And why did she decide – ill health aside – that Sanditon wasn’t worth continuing? We can make educated guesses, but ultimately this is a kernel of literary mystery, an uncut diamond, that promised a shift in Austen’s way of thinking of the world, with its slightly more acerbic tone and refreshingly novel setting, but a way of thinking that she clearly felt unable to bring to fruition.

Kathryn Sutherland’s always fascinating thoughts in the introduction to OUP’s edition of Sanditon are well worth reading to give some context and fuel your own theories of what Sanditon adds to our understanding of Austen’s evolution as a writer towards the end of her life, as well as what the fully-fleshed novel might have become. She raises the very valid point that this is Austen’s only novel written after the Napoleonic wars, a conflict that overshadowed almost her entire adult life. As such, the world she was writing Sanditon in was one newly at peace, and one poised for change. The choice to set the novel in a seaside resort that is being constructed for a new age of leisure tourism exemplifies this perfectly. Mr and Mrs Parker want to capitalise on the new craze for seaside bathing by developing Mr Parker’s family land in the small, nondescript seaside village of Sanditon, with the help of the twice-widowed and very wealthy Lady Denham, doyenne of Sanditon society. This allows Austen to dwell on one of her favorite topics – hypochondria – with much caustic wit – but also to widen her social lens as she brings a disparate group of people, including a mixed race heiress – to Sanditon to enjoy the waters and brisk sea air. The narrative focus of the novel appears to be Charlotte, a young family friend who is taken to Sanditon by the Parkers, but she is not fully fleshed, and feels rather wraith-like compared to the more robust characterisation of Mr Parker and his wonderfully hypochondriac siblings. I wondered whether her difficulties with bringing Charlotte to life had contributed to Austen’s lack of enthusiasm for finishing Sanditon, or whether perhaps, outside of the close village or house-based communities of her other novels, Austen felt – excuse the pun – rather at sea with what to do with a more transient community of holidaymakers.

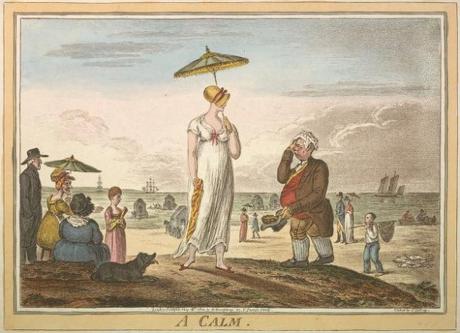

Austen is known for depicting the seaside as a place of danger, disaster and loose morals – think of Lyme Regis and poor Louisa, of Wickham seducing Georgiana Darcy in Ramsgate and then Lydia in Brighton, of Mr Woodhouse’s fear of Isabella and her children going to the sea, of the dingy Portsmouth home of Fanny Price – and so her decision to set an entire novel at the seaside, amidst a resort set up by two rather unlikeable speculators – is fascinating and intriguing on many levels. In the brave new world of post-war England, in a world where everyone was away from home and looking for pleasure, what shenanigans would Austen have dreamt up, and what would this have told us of her vision of early nineteenth century society? How sad I am that we will never know. Despite my reservations regarding reading deliberately unpublished work, I am so glad I have read this, for it has given me much to reflect on and added a richness to my reading of her completed novels. In Sanditon, though but a few pages, we see an author entering into a new phase of thinking about, experiencing and expressing her rapidly changing world, and even though we can only speculate as to how she would have finished this tale, that only adds to the pleasure of the reading experience. Sadly I have heard nothing but bad things of the TV adaptation, which is essentially a work of Andrew Davies’ imagination, considering the limited textual material he had to go on. I might give it a go this weekend, though – with the growing nip in the air here in beautifully autumnal London, I can’t resist a period drama on a Sunday night, even if it does turn out to be terrible!

Advertisements