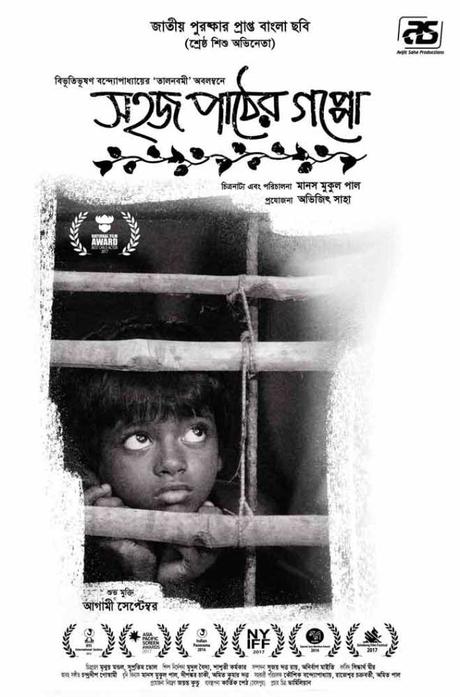

Sahaj Paather Goppo , subtitled 'Colours of Innocence', is a Bengali feature film, released in 2016 at select film festivals and later again in September 2017 in theatres.

The film was produced by Avijit Saha and directed by Manas Mukul Pal.

The film made an entry into the Mumbai Film Festival 2016, and was selected for the Indian Panorama section at the International Film Festival of India, 2016. It was also invited to the New York Indian Film Festival of 2016, where it was nominated in two categories (best film and best director) and to the Goteborg Film Festival of 2017.

The film is an adaptation of Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay's short story Talnabami from the short story collection of the same name. The story is briefer in scope, whereas the film is more layered and goes into deeper explorations of character and disillusionment.

The most unique of honours came from India herself, when the two child actors who delivered beautiful performances in the lead roles received National Film Awards in 2016 in the Best Child Artist Category; something no Bengali feature has received since (1988).

The film is an adaptation of Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay's short story from the short story collection of the same name. The story is briefer in scope, whereas the film is more layered and goes into deeper explorations of character and disillusionment.

On being asked about the title of the film in an interview, Pal said it was a tribute to Rabindranath Tagore, whose famous book for children, Sahaj Paath, has been nothing short of a milestone in Bengali children's literature.

The film itself is an exploration of two childhoods, the tribulations that threaten to bring the childhoods to an end, finally ending on a hopeful note with the children still certain that things will turn out well.

The narrative is so simple that at some point it ceases to feel like fiction. Like the trailer says, it is "a tale of life" indeed.

The story in short: In an unnamed village in Birbhum, West Bengal, live two brothers, Gopal (Shamiul Alam) and Chhotu (Noor Islam). Their father, a cycle-van driver and the sole breadwinner of the family is bed-ridden after being badly injured in a road accident. The children find themselves without decent meals, surviving on cheap puffed rice and salt.

Gopal soon finds himself being pulled out of school and doing odd jobs for families in the village. Chhotu is his inseparable companion. Some employers offer him an odd chapatti or something else to eat, which the two brothers share. Life is not smooth but they make do. Gopal also laboriously picks "kalmi" leaves from the pond and sells them at the market along with palm fruits which he gathers from the ground when it rains.

He grows up, despite his tender age, thanks to the responsibility.

His brother too, finds himself disappointed by society and sees a glimpse of the true world in its indifference.

The film itself is an exploration of two childhoods, the tribulations that threaten to bring the childhoods to an end, finally ending on a hopeful note with the children still certain that things will turn out well. The narrative is so simple that at some point it ceases to feel like fiction. Like the trailer says, it is "a tale of life" indeed.

But what makes this story worth telling?

Especially something so commonplace and mundane. One can argue that the sheer beauty of rural Bengal and its sights and sounds are enough, but it is not so.

Despite being set in an unnamed little village in Bengal, the story is a basic one, one of loss of childhood illusions.

The difference being, like the book used to teach children words and basics of language and literature, the film showcases how two children learn from life and end their story on a hopeful note. Illusions shatter, but it's a learning curve.

This happens in two dream sequences.

The first: The elder brother Gopal wakes up one morning, to find his mother silent and distraught and his father's dead body laid on the ground. His mother (Sneha Biswas), who is standing by expressionless, hands to a crying Gopal a tattered old schoolbag, where the family's meagre money is hidden.

And as soon as he takes the bag, she runs while a crying Gopal chases her, screaming "Mother don't go!" throughout. She is of course running towards the railway track to commit suicide. As Gopal closes the distance in, in utter frustration, his mother picks up a rock to throw at him if he doesn't let go saying how they are penniless; there's not enough money to even give him his last rites. She goes and throws herself before a speeding train while Gopal sits screaming and crying.

It is a heart wrenching scene, to say the least. One realises that the situation on-screen isn't just caused by the child's fear, not just made to pull at the audience's heartstrings. Not only is it truly the situation for millions of people in the world, but there is a strong cause-effect relationship going on here:

The dream at once jerks Gopal into a practical existence as he takes up as many ways to earn money as he can. However, being nothing but a dream at the end of the day it remains just bitter enough to produce a jerk but not leave an aftertaste.

The second dream in the film is a far more personal and far more naïve one, and is part of the pivotal moment of the story.

The difference being, like the book used to teach children words and basics of language and literature, the film showcases how two children learn from life and end their story on a hopeful note. Illusions shatter, but it's a learning curve.

Chhotu has never really had what one might call tasty food in his brief life. One market day, while returning home after having sold vegetables and a palm fruit, the brothers encounter a friend who informs them that the Seths (the richest family in the village) will have a big celebration at their house two days from then for Janmashtami (Krishna's birthday). He tells them how everyone in the village will be invited. Chhotu of course is absolutely elated about this; his eyes positively light up on hearing that they will serve (among other things) "poloa" (pulao). Gopal however sees an opportunity to earn a substantial amount of money. Janmashtami is the time when palm fruit sweets are consumed, which would mean a chance to sell some.

So he takes his brother, to the house, which is an absolute palace compared to the huts they are used to seeing. The mistress of the household, Lakshmi (Shakuntala Baruah) meets them and she is happy enough to tell them to get good palm fruits for the puja after Gopal quotes a price.

Chhotu in his childish naiveté, asks "Dada don't take money for the fruits. They won't invite us then." Of course, for the audience it is obvious: when someone says "everyone" they don't mean everyone, moreover, if she had to invite them, Lakshmi would have done so as soon as she met them. So when Gopal reprimands him, it is only justified.

In a beautifully shot poignant sequence, the poor child is seen expectantly turning back every other second to see if she says anything about an invitation. But no invitation comes.

Even his mother when told about the dishes they would be serving at the celebration, mumbles "Can't even manage white rice and dreaming about pulao."

The next day is a rainy one. There are strong winds blowing. Gopal is bedridden with a fever.

Chhotu gets up early in the morning, takes a tattered old umbrella and a piece of tarpaulin and trudges to the palm grove and picks up four of the biggest palm fruits he can find and takes them to the Seths'. There he refuses to take money for them and takes his leave.

In a beautifully shot poignant sequence, the poor child is seen expectantly turning back every other second to see if she says anything about an invitation. But no invitation comes.

Chhotu goes home and looks at the sky from his window and asks God, "they will invite us, won't they God?" and replies to his own childish fantasy smiling, saying "Really?"

Gopal comes back and slaps him till he cries for doing what he did. He says how if they had to invite them, they would have already; that by giving away the fruits, he made Gopal's efforts futile. After all he had gone to pick fruit with a high fever. The violence stops when their mother intervenes. Chhotu still holds on to the belief that they will be invited and keeps saying so with tears in his eyes.

Gopal makes up with his brother after promising to buy him candy the next day. There is too much love between the two brothers for them to actually be sad. It is that same love that keeps them afloat through their rough lives.

The invitation arrives, with the Seth's servant in the morning. Chhotu and Gopal, very evidently put on their only good pair of clothes and go to the puja.

Lakshmi herself pats Chhotu on the head as he gorges himself on the delicious "poloa".

This is where he wakes up and asks his mother, "What day is it today, mother?"

Later in the day Chhotu is given a full meal of white rice and boiled greens; things he would normally love to eat. But with the near unimaginable "poloa" on his mind, nothing else can get him to smile.

Only later his friend Gojo and his brother are seen going to the Seths'. In the ensuing conversation, it is clarified that since they are the children of a van-driver, they aren't invited. Chhotu with tears in his eyes and a broken heart screams at them "I will never go anywhere ever again."

This is where something else that forms a dominant part of the plot of the film should be discussed: The way the director treats privilege.

Privilege is made of the smallest of things people take for granted thanks to their economic, educational and social life. This same phenomena make it very easy for one party to accept certain things while making it almost impossible for another to do the same.

Privilege is made of the smallest of things people take for granted thanks to their economic, educational and social life. This same phenomena make it very easy for one party to accept certain things while making it almost impossible for another to do the same.

An example of this would be someone's birthday. For most of us urban citizens, it is a very obvious, natural thing; to such a point where we actually expect others to remember our birthdays and celebrate them.

Even remembering each other's birthdays is quite a common thing; no one really gives a thought about it.

This basic thing, is beautifully critiqued in the film through Chhotu. A birthday is a luxury when you don't have enough to fill your belly: His mother dismisses his question, "mother when is my birthday" by sleepily mumbling "I don't remember."

No matter how commonplace a birthday is, for us: it is the Chhotus and Gopals who make up the majority.

The second example of how the director treats privilege is set at the house of one of the richer families of the village. The mistress of the house, Shyama had asked Gopal to come clean their mildew-encrusted well up. Chhotu accompanies his brother simply because there is a promise of food in the venture.

The brothers arrive. Shyama's husband Shambhu ushers them into the courtyard, where they stand. Shyama meanwhile gets her child (who is about the same age as Chhotu, might be a bit younger) ready for school with utmost affection and care. It is very clear that the child doesn't really want to go to school.

Chhotu in his childish naiveté, asks "Dada don't take money for the fruits. They won't invite us then." Of course, for the audience it is obvious: when someone says "everyone" they don't mean everyone, moreover, if she had to invite them, Lakshmi would have done so as soon as she met them. So when Gopal reprimands him, it is only justified.

Gopal and Chhotu look at him with a feeling resembling jealousy: the envy of the two brothers however is for different grounds.

Gopal's wounds are fresh. Education has become a luxury for him only recently, with his father's accident. The poor child had cried himself to sleep when told to pull out of school.

For his brother the thought that Shambhu's son gets a proper midday meal at his school which includes rice, lentils, vegetable curry and eggs sometimes, is a wonder.

Gopal gets working on the well however, scraping and scrubbing. Chhotu plays around and helps him when asked to.

Soon he finds colourful rubbery things lying just outside the bedroom window of the house. He goes and asks Gopal if they are balloons.

(At this point, it is very obvious to the audiences what they are.)

Despite Gopal's reprimands (who doesn't understand what they are either) to not touch them, Chhotu fills one up with water and innocently plays with it.

At this Shyama gets very vexed and scolds the two children quite a lot. She hands them a measly bit of money and practically chases them away for being shameless. She doesn't even give them any food.

Even though Shyama and the children are residents of the same village, the families belong to very different social and economic backgrounds, which is why it does not occur to Shyama that these children might actually not know what a condom is.

She seems to have completely forgotten that her employees are essentially children owing to the fact that they are working to make ends meet; acting as the breadwinners of their family. Gopal and Chhotu might have lost their chances at fully realising their childhoods, but they are still children and of roughly the same age as Shyama's own son.

The Seth sequence is a much more skilful demonstration of this because it is personal.

The child very innocently gives them away to Lakshmi, the mistress, hoping to get eat something good for the first time. She however doesn't even bat an eyelid and doesn't even insist too much about paying.

The director leaves it to the audience to decide, if it was wrong for Lakshmi to accept the fruits from a child who is very obviously poor and not even invite him to the celebration.

But what is more important here is the privilege she exercises.

The Seths are very obviously a wealthy family, true country gentry one may say. The question of the film is not if it was fair or not; the issue at hand is how easy it is to accept favours and services for the upper classes, with no qualms or consideration, appearing just kind enough to keep the image up.

The word "tragedy" has been reduced and simplified to mean a story with a sad ending. The word however, came to us from Ancient Greece where it was held as the greatest of theatrical and visual arts.

Aristotle, from whose definitions of art, all future criticism derives, defined tragedy as a story in which the character is up against something insurmountable or impossible to defeat. It could be fate or it could be the gods. The best kind of tragedy ended with hope for eventual redemption.

Two children fighting to put food in their bellies, in a society which fails to recognise their childhoods is then the greatest extent to which a tragic heroism can go, in today's world.

The fact that the children fail to give up their hopes till the end of the tale despite having to fight for existence each and every day then, becomes their greatest triumph.

There are invisible voices in each and every one of our lives; voices we either can't see or don't want to. We pass these voices in our homes as they do our household chores, on the pavement as they beg for sustenance and in our workplaces too, as they fetch us tea and do odd jobs for us.

The world of cinema and the world in general needs stories like Sahaj Paather Goppo to be told because these voices do not deserve the off-handed dismissals they receive.

They fight harder than most of us and films like this recognise that heroism.