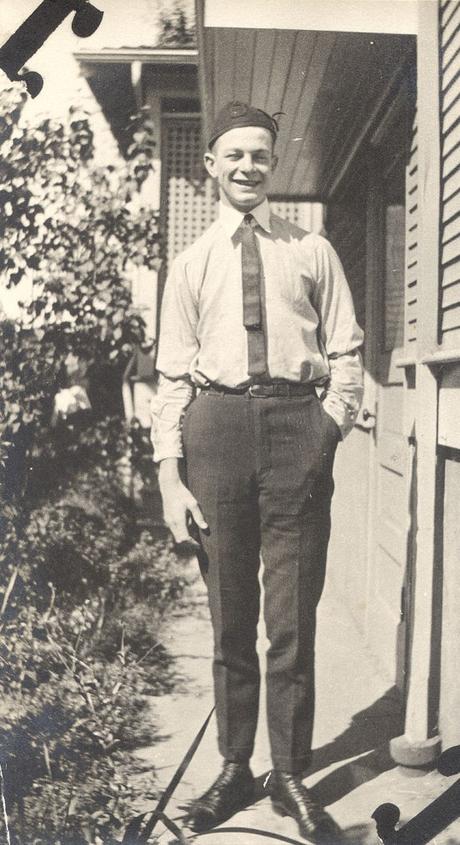

Pauling outside his boarding house, first term of his freshman year at OAC.

[Part 3 of 4 in our examination of the Oregon Agricultural College that Linus Pauling came to know during his freshman year. Fall 2017 marks the one-hundredth anniversary of Pauling’s enrollment at OAC, known today as Oregon State University.]

Each year, students arrived from around the state, country, and abroad to attend Oregon Agricultural College. For the 1917-18 school year, OAC boasted a student body of over 4,00 men and women. Long requested by the student body, the number of college personnel also began to rise that year, with totals nearing 200 faculty members. And despite the onset of American involvement in World War I during the previous spring, OAC’s fall 1917 registration was its largest ever. Contributing to this was the fact that more women had enrolled for the 1917-18 school year than had ever previously been the case at the college.

One member of this large first-year class was a sixteen-year-old Portland resident, Linus Pauling. Once arrived in Corvallis, Pauling, in his diary, described his living situation, a boarding house close to campus, noting that “I have a nice big room, much larger than two boys usually have. I will share it with a sophomore named Murhard.” He likewise recorded these observations of two other young men sharing a room in the same house

they are two rooks; one, a 20 yr. old talkative fellow, named Hofman, weight 175# and always talks about his girl, Millicent, nicknamed “Titter.” The other, Henry, is a very quiet, small young man, but slightly deaf. He will take Commerce, and Hofman will take Forestry.

Pauling left the boarding house after Fall semester and, because he was unable to find a permanent place of residence, he often wound up staying with friends during the Spring. Viewed through a modern lense, it would not be a stretch to say that Pauling was effectively homeless for this period of his studies at OAC.

Early on, Pauling expressed a great deal of insecurity in his potential to excel at the college. It did not take very long, however, before he discovered that his merit in academics had very clearly carried over from his high achieving ways in high school.

During the fall semester, Pauling registered for a typical collection of first-year classes, including Modern English Prose, Drill, and Gym. In addition, he began working through the core curriculum for Chemical Engineering majors, taking courses like General Chemistry, Mining Industry, and Calculus.

As he moved forward through his coursework, Pauling found that his high school education, though incomplete – he had not taken a required history class and did not graduate from Washington High School – was more than satisfactory. So pleased was he by the preparation that he had received for college, that he wrote a letter thanking his high school math teacher, Virgil Earl, for having done an exceptional job.

Earl replied to Pauling with gratitude and encouraging words, saying, “you have the ability and the disposition to work so I feel sure that you will succeed in your chosen work.” Earl’s point of view would soon be reflected by waves of praise and admiration extended by many of Pauling’s OAC professors.

Pauling wearing his “rook lid,” ca. 1917.

Student functions played an outsized role in the undergraduate experience at Oregon Agricultural College. Activities and meetings were held each week and larger gatherings, such as dances, were hosted with great frequency.

Socially, the school year was underway once the YWCA-YMCA welcome reception had been hosted. This event, which was basically a dance, was put on by the two clubs to familiarize first-year students with the social dynamic of their new home. The 1917 welcome dance took place in the Men’s Gym (now Langton Hall) where the College president, William Jasper Kerr, kicked off festivities by addressing the assembled student population. The rest of October saw Mask and Dagger theatrical auditions, a senior reception held for the “frosh,” and an informal band dance. Class and student body elections also took place at the end of October.

In addition to cultivating a culture of of student involvement, the college did its best to stoke long-running social traditions. Pauling took these rituals seriously and commented on how they had strengthened his school spirit. By the end of his first month in college, he noted in his diary that “I am getting along alright. Have lots of beaver pep.”

The Burning of the Green, 1925.

Central to many of these traditions was one’s class standing. First-year students were colloquially called “rooks” and “rookesses,” and were made to wear green caps (for men) or ribbons (for women) to denote their status. At the end of the year, students burned their “frosh” paraphernalia in a bonfire held just south of the Women’s Gymnasium.

Beyond hats and ribbons, amicable competitions and friendly rivalries between grade levels was an aspect of life at OAC which continued year round. Many of these events were staged during Homecoming, which took place annually during a fall weekend and focused intently on the college’s athletic teams as well as class rivalries. Sophomores and freshmen went head to head in both a bag rush and a football game, while all class levels participated in a three mile cross-country race. Intercollegiate sporting events during the 1917 Homecoming weekend included a soccer game between OAC and the University of Oregon, which O.A.C won, as well as a 6-0 home loss in football to Washington State College.

The 1914 OAC Freshman-Sophomore Bag Rush.

The culminating event of the weekend was Sunday’s open house, during which undergraduates met and talked with alumni who had returned to campus. Of this experience the Beaver yearbook recounted, “all in all, it was a great success and the old fireplaces again welcomed familiar faces, and the undergraduates listened to stories of the ‘Good Old Times.'”

Another annual happening, The Co-Ed Ball, was held solely for the women of the college. Unsurprising, given the rising number of women attending OAC, 1917’s Co-Ed Ball was the largest in school history, with “four hundred women being present.” The supervisors of this specific occasion included Mary Fawcett, the Dean of Women, and Ida Kidder, the college’s beloved librarian, known to many as “Mother Kidder.”

Performers in the Women’s Stunt Show, 1925.

The women of the College also sponsored the “Women’s Stunt Show,” for which every women’s organization on campus prepared and performed a skit. In addition to competing for a trophy, the Fawcett Cup, the ultimate goal of the Stunt Show was to raise funds. The 1917 edition succeeded on this front as a total of $400 was collected, with $200 apportioned to the YWCA.

In December, as the end of the term neared, the Intercollegiate Oratorical and Debate Society won its Annual Dual Debate against the University of Oregon. Other notable winter events included two Mask and Dagger shows: “Why the Chimes Rang” and “The Magistrate.” The Military Ball and the Interfraternity Informal rounded out a busy fall calendar for Linus Pauling and his fellow students at Oregon’s land grant college.

Advertisements