Note: This is another post in a continuing series on evolutionary theories of religion. The previous post in this series is “Durkheim’s Elementary Forms.”

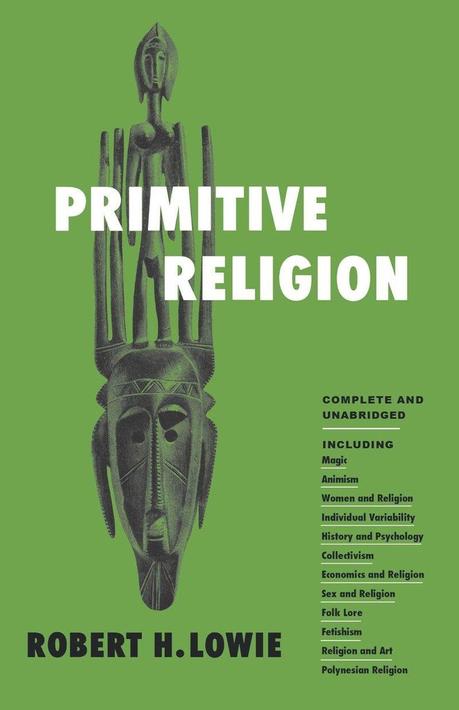

Robert Lowie’s Primitive Religion (1924) was, in large part, a reaction to Durkheim’s Elementary Forms. Unlike most British anthropologists who were enamored of Durkheim’s ideas, Lowie was unimpressed. Lowie complained that under Durkheim’s hegemonic social scheme, individuals and psychology were wholly absent. There was no room for thought, creativity, independence, or transformation. Given the total dominance of society, it was unclear how individuals could think for themselves or how society could ever change.

In contrast to the cloistered-scholar Durkheim, Lowie had spent several years doing fieldwork among Native Americans or so-called “primitives.” He found that individuals in those societies often had novel feelings and ideas that resulted in change over time. While Lowie applauded Durkheim for calling attention to previously neglected social and symbolic aspects of religion, he faulted Durkheim for concocting a metaphysical and speculative scheme not supported by either ethnography or history. Little of what Durkheim described as being true of all “primitives” was true of Native Americans.

Lowie lodged several other criticisms, all well-taken. He observed, in some detail, that Durkheim had selectively read the Aboriginal record and presented a distorted picture of Aboriginal worldviews. Durkheim had mistakenly presented local traditions as pan-Aboriginal, and completely ignored the ways in which those worldviews had transformed through time. As a consequence, Durkheim treated Aboriginals as prehistoric relics or a society stuck in time. They were not, Lowie asserted, “primitive” exemplars of the evolutionary past or an earlier stage of cultural development. Finally, Lowie noted that Durkheim’s entire scheme was founded on the factually mistaken idea that totemism was universal and constituted the earliest form of religion. As a matter of ethnography and history, Lowie observed, this was false.

Lowie’s lengthy critique of Durkheim (and corresponding defense of Tylor’s cognitively oriented animism) was perceptive and potent. It was also largely ignored. There were several reasons for this. First, Lowie’s response came twelve years after the publication of Elementary Forms – by this late date, Durkheim’s claims had been accepted by British anthropologists and assimilated into their functionalist schemes. Second, Lowie coupled his critique of Durkheim with a pallid plea for more work along diffusionist-historicist (i.e., “culture area”) lines. He argued that more ethnographic data was needed on cultural variation, frequencies, and patterns. After all this data had been gathered and historical influences traced, theory could be formulated and tested. This after-the-fact theorizing appealed to no one, and struck many as backwards: theories should come first and these should be tested with data.

Finally, Lowie argued that Tylor’s psychological approach to religion was largely correct, though it required revision. Agreeing with Marett’s “animatism” supplement to Tylor’s “animism,” Lowie argued that the most poignant aspect of “religion” was a feeling generated by encounters with the unexpected, surprising, and extraordinary. Lowie’s work with Native Americans had convinced him that “spirit” concepts were far less important than a sense that there were larger powers or forces at work and these manifested in strange and inexplicable ways. Wherever and whenever these powers were sensed, something like “religion” was present.

This feeling was most evident, Lowie asserted, among indigenous peoples that he reluctantly called “primitives.” Though Lowie asserted that his use of “primitive” did not imply time or entail evolution, it apparently struck many as doing both. Because evolutionist schemes had fallen distinctly out of favor by this time (i.e., 1924), Lowie’s book had little impact among anthropologists. It did, however, provoke a reaction from Lowie’s friend and colleague, Paul Radin. Radin’s reaction (and book) will be subject of the next post in this series.