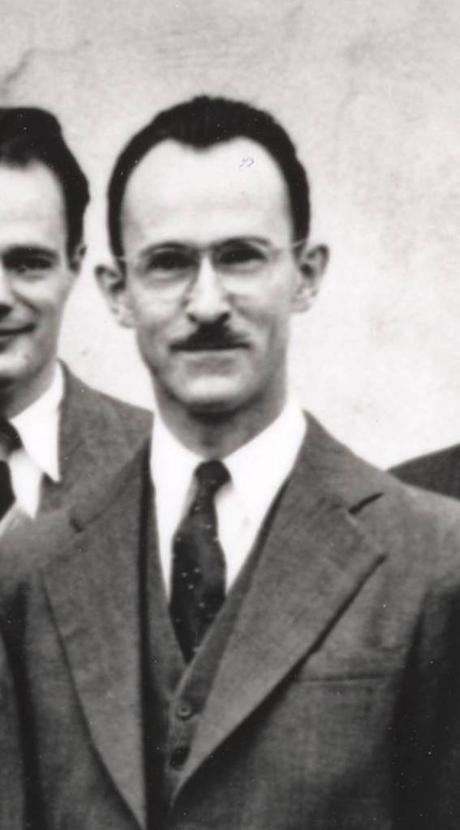

Robert Corey

Robert Corey[Pauling and the Guggenheim Foundation]

In 1949, as the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation tested out its new style of fellowships for established researchers, scholars, and artists, Linus Pauling put forth his California Institute of Technology colleague Robert B. Corey as an ideal candidate for funding. Corey was researching the crystal structure of amino acids, peptides, and proteins, and wanted to develop more refined molecular models to supplement his experimental work; Pauling estimated he would need about $3,500 to do so. Corey did not make it into the first group of new fellows for that year, but Pauling suggested him again the following year and he was approved.

Corey’s accepted project had grown from the year before. A Dr. Palmer, who worked under F. O. Schmitt at Caltech’s Department of Agriculture Regional Laboratory in Albany, California, had been taking x-ray photographs of lysozyme, the bacterial protein found in tears. Palmer no longer had the time to continue the work, but he and Corey thought a trained assistant could come in and continue taking the photos. These would then be brought back to Pasadena for analysis and interpretation in the Corey lab. Pauling wrote to Guggenheim administrator Henry Allen Moe that this was a “very important job” that fit nicely within Caltech’s broader program of protein structure determinations.

When Corey’s case came before the Committee of Selection, evaluator E. B. Wilson suggested that Corey struck him as being a good candidate for Office of Naval Research funding, and as such he would not need Guggenheim support. Upon hearing this, Pauling clarified in a letter to Moe that the circumstances were not quite so straightforward.

As Pauling explained, after Corey applied for the Guggenheim Fellowship, the Office of Naval Research had indeed approached him about a potential collaboration. Pauling followed up by submitting an application for funding, but he had yet to hear back about final approval. He had, however, been informed that the funds, if granted, would come in at $25,000 less than requested. Furthermore, both Pauling and Corey did not like the idea of all their work being backed by the Navy. (By then, Pauling had already made the decision for himself that he would refuse to accept any armed forces funding.)

More importantly, Pauling told Moe that the progress made at Caltech in the last three years was the “greatest advance in the protein field” since Emil Fischer’s discovery that proteins were polypeptides, some fifty years prior. Pauling’s letter was persuasive and the Committee granted Corey $15,000 over two years.

Corey knew that Moe wanted to meet each fellow in person, and so when he was in New York shortly after the beginning of his fellowship in September 1951, he stopped by the Guggenheim Foundation offices. Moe was not there, but Associate Secretary James F. Mathias was available, and the two enjoyed a pleasant conversation. During that trip, Corey needed to go to Connecticut for a week and decided he would try again to meet with Moe afterwards. This time he called first to see if Moe was in the office, and was told that Moe would not see anyone unless it was very important. Because of the brusqueness of the reply, Corey decided against attempting to arrange any future introductory meetings with Moe.

Over a year later, Pauling suggested that Corey stop to visit Moe while on a different swing through New York. Corey was hesitant to do so, explaining what had happened the first time around and adding a new complaint about Moe’s failure to reply to a letter from Corey about his income taxes. Pauling immediately wrote to Moe to find out more from the secretary’s perspective.

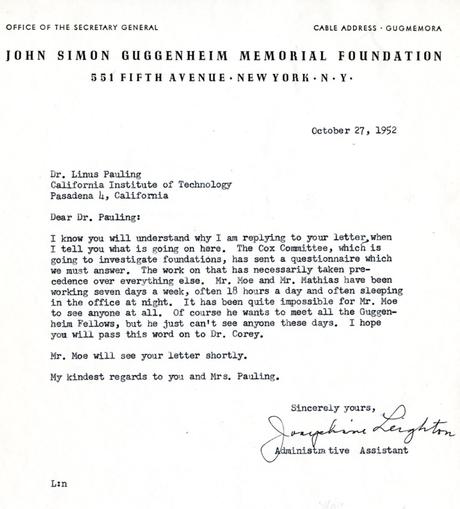

Unbeknownst to Pauling, at that time Moe and Mathias were in the midst of answering a questionnaire issued by the House of Representatives Select Committee to Investigate Tax-Exempt Foundations and Comparable Organizations, also known as the Cox Committee. Moe’s assistant, Josephine Leighton, responded to Pauling and, while misunderstanding the exact circumstances, attempted to address his concerns by explaining that Moe had just been too busy, working up to eighteen hours a day on the Cox response. Leighton assured Pauling that Moe wanted to meet in person with all the fellows, but simply could not fit it into his schedule at this time.

Pauling clarified that he was describing an event from the previous year, but did not want to bother Moe any further with the matter and told Leighton that it could wait. Nonetheless, Leighton dug deeper and figured out that Moe had been in Washington when Corey had originally visited. She could not, however, explain the unpleasant telephone call, as the expectation was that no one in the office would act that way. She also could find no record of Corey’s letter about his income taxes.

After a few more weeks had passed, Pauling assumed that Moe had finished up his work responding to the Cox Committee and wrote Moe about concerns that he had regarding the public’s perception of the foundation. In particular, it was Pauling’s impression that the granting organization was no longer seen as significant among the most able of scholars, scientists, and artists. This was mainly due to the foundation giving out comparatively smaller amounts than had been the case when Pauling was a fellow in the mid-1920s.

When he received his award, Pauling noted, he was granted $3,500, which was about $1,500 more than the sums offered by National Research Fellowships or the post-doctoral salaries then available at Caltech. By the time of Pauling’s 1952 letter, Caltech’s post-doctoral salaries had reached $4,000 to $4,500, and the pharmaceutical company Merck was providing grants of $6,000 plus traveling expenses. To keep up with this competition, Pauling thought Guggenheim Fellowships should generally average out to $6,000 plus traveling expenses.

Pauling sent a copy of his letter to Louis B. Wright, chair of the Committee of Selection. Wright agreed with Pauling’s point of view, noting that, increasingly, only scholars and scientists from wealthy schools equipped to grant sabbaticals were able to accept Guggenheim Fellowships. Wright, like Pauling, enjoyed the privilege of an extensive Guggenheim stay in Europe in 1928-1929, a trip that would only last six months in 1952 and not much longer were the person to stay at home. Given the choice, Wright felt it better to reduce the number of fellows and increase stipend sums granted.

Moe could not reply to either letter as he was still too tied up with his response to the Cox Committee. He would eventually address Pauling’s concerns, but first the two would need to resolve what developed into a major argument over how the Foundation had handled the Cox Committee questionnaire.