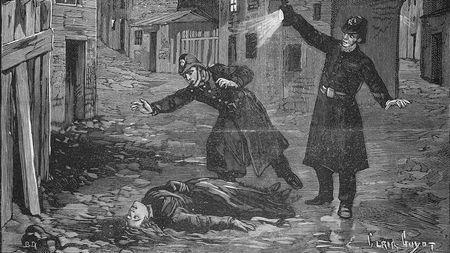

When I lived in East London, it was a common sight in the early evening to see hordes of people gathered outside the Ten Bells pub in Shoreditch, often dressed up in nineteenth century costume, preparing to go out on a Jack the Ripper walking tour. The pub itself, frequented by one of the victims on the night of her murder, holds a morbid fascination for many, who crowd into its authentically nineteenth century bar to experience a frisson of macabre pleasure at being a hair’s breadth from history. I have been on one of these tours myself; after studying detective fiction with my students a couple of years ago, they begged to go on a walking tour of Jack the Ripper’s London, and so, in the gloomy light of an autumn evening, we trod in his footsteps as we meandered our way through what was once a foetid warren of passages and alleys. These notoriously vile slums were the home of London’s destitute – the poor, the abandoned and the sick, all piled in together, spending their days doing whatever they could to scrabble together the pennies for a night’s lodging, and, if they failed to do so, finding a bed on the muck-encrusted pavement instead. Nowadays these streets are largely gone, razed to the ground by those seeking to stamp out vice at the end of the nineteenth century, or destroyed during the war. Now they house glass and steel skyscrapers, luxury apartment blocks, and hipster shops and restaurants. The Ripper certainly wouldn’t recognize this district any more, but despite the transformation of Shoreditch, his legend still haunts its streets. As we stood and listened to the description of the murders, the air became chill, the darkness more intense. Neither the comforting glow of the street lamps nor the anodyne modern architecture could lift the sense of unease I felt. Now, having read Hallie Rubenhold’s marvelous book about the victims of Jack the Ripper, I wonder whether part of that unease was the fact that I was taking part in an industry that treats the brutal murders of five women as mere light entertainment.

These women have become like the cardboard-cutout characters in an Agatha Christie novel – they are barely even registered as having been human, with lives of their own, that they didn’t deserve to lose. Is that because, as Rubenhold skilfully explores, that they have always been dismissed as ‘just prostitutes’? This categorisation has contributed to the belief – encouraged by contemporary newspaper accounts, and repeated ever since – that these women deserved their deaths. They were asking for it. They shouldn’t have been out on the streets at night. They only had themselves to blame. And so they have been forgotten, their names barely remembered – whereas their murderer – a man – enigmatic, mysterious, so clever he has never been discovered – has become a legend, someone even to be celebrated and revered. Rubenhold’s book is the first to redress this balance, placing the five women murdered by Jack the Ripper and their lives at the forefront of the story. Their murders are not even discussed, and Jack the Ripper’s name is barely mentioned; instead, this is an account of five ordinary lives, all of which are a fascinating study of how so many women in the nineteenth century lived on a knife-edge where one poor decision, one tragic loss, one period of illness, one missed rent payment, could send you plunging from a respectable existence into destitution, with no way back.

Annie Chapman lived a comfortable life with her husband and children on a leafy gentleman’s estate in the countryside; the daughter of a soldier, she had gone up in the world by marrying a coachman, and should have been content with her existence. But she had developed a penchant for alcohol, and her addiction grew harder and harder to manage. The death of her eldest daughter eventually tipped her over the edge; despite her husband and sister placing her in a sanatorium to find a cure for her alcoholism, she couldn’t manage to stop drinking. Her husband, at risk of losing his job on the estate and so his means of supporting their remaining children, had to cast her out. Homeless, destitute, unable – or unwilling – to seek help from her family – she became one of the thousands of unfortunates roaming the streets of London, eking out a day-to-day existence on the few pennies they could beg. She was killed while she slept on the streets of Whitechapel. There was never any suggestion from those who knew her that she had exchanged sex for money. The other women who were killed had depressingly similar stories. Due to addiction, abuse or abandonment, all found themselves on the streets, going from workhouse to workhouse, dosshouse to dosshouse, as they attempted to keep a roof over their head at night and some food in their bellies. Most were wives, some were mothers. Only one was known to have worked as a prostitute, and even that was only because she had no other option open to her. In a society that shunned women who didn’t fit the middle class ideal, that blamed women for sexual transgression while men could walk free, and that provided little to no opportunity for a woman to support herself without a male companion, these women were not just victims of a serial killer – they had, in many ways, already been murdered by a patriarchal system that had stacked the cards against them before they were even born.

The Five is fascinating and heartbreaking in equal measure. For anyone interested in women’s history, this is a must-read. I can’t recommend it highly enough.