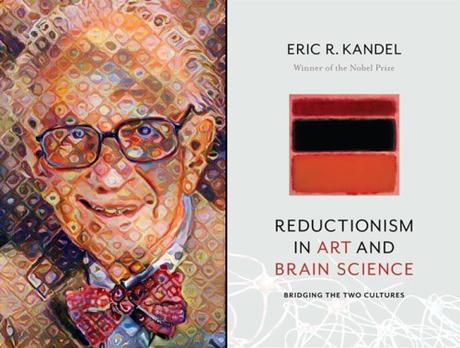

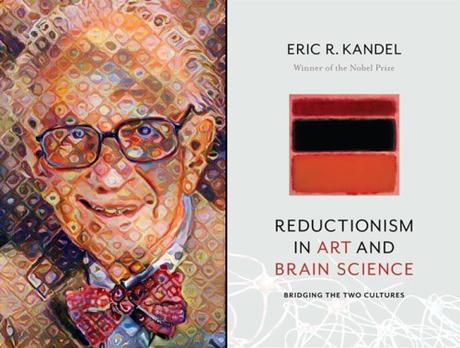

Left, photo of Eric Kandel that I modified using Deep Learning Style Transfer and Chuck Close as a Filter and Photoshop.

Left, photo of Eric Kandel that I modified using Deep Learning Style Transfer and Chuck Close as a Filter and Photoshop.

“We are closer to attaining cheerful serenity be simplifying thoughts and figures. Simplifying the idea to achieve an expression of joy. That is our only deed.” – Henri Mattise

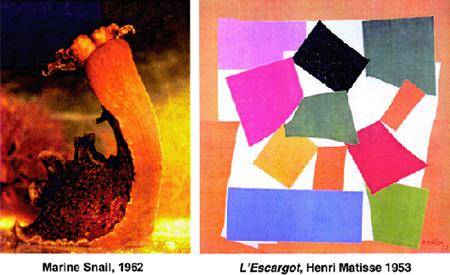

I’m of the opinion you should never trust a Nobel Prize winner[1], or at least pay them no more attention than your crazy uncle on any subject outside their expertise, so I was skeptical when Columbia Publishing sent me a copy of Eric Kandel’s new book: Reductionism in Art and Brain Science. Kandel won a Nobel studying sea snails, I mean I’m sure he’s a smart guy, but do I really care what he has to say about Mattise’s The Snail? Turns out I do, and that this book isn’t a flight of fancy for Kandel. It contains ideas he’s been working on since 2002, and taps his expertise in neuroscience, his skills as a textbook writer in explaining neuroscience succinctly, and his clearly deep and authentic love for modern art.

Kandel begins his book discussing an idea from the molecular physicist turned novelist C. P. Snow that there is a fundamental divide between the cultures of the sciences and humanities, and we must strive to bridge this chasm. Snow argued science is concerned with the physical nature of the universe and the humanities are concerned with the human experience. Kandel thinks that neuroscience is edging ever closer towards the exploration of human experience and may be the bridge that connects the cultures of the arts and the humanities. This book represents his humanistic attempt to draft plans for a bridge, that may in the future connect science and the humanities.

Kandel begins with the observation that in the mid-20th century biologists and artists both explored reductionism in their fields to try to discover fundamental truths. Biologists used reductionism make large and complex systems tractable and experimentally manipulable. For example, Kandel, although interested in human memory, chose to study sea snails which have only 20,000 neurons compared to the 100 billion in the human brain, and this allowed him to make important discovers. Meanwhile, abstract expressionists experimented with art, learning how to reduce art to it’s bare minimum components that could still evoke emotional responses and that challenged viewers to think in new ways. Beyond this coincidence though, Kandel argues that as neuroscience has developed and our understanding of the visual system increases, we are gaining insights into how our brain processes this abstract art and how it elicts unique neural responses that we don’t get from photo-realistic or figurative art.

Throughout his carreer, painting prodigy J.M.W. Turner’s style became more abstract. Left, The Shipwreck, 1805. Right, Snowstorm: Steamboat Off a Harbour’s Mouth, 1842.

Throughout his carreer, painting prodigy J.M.W. Turner’s style became more abstract. Left, The Shipwreck, 1805. Right, Snowstorm: Steamboat Off a Harbour’s Mouth, 1842.

The book is about two-thirds art history, and one-third neuroscience about how we processes art visually and emotionally. As someone who enjoys art, but never took an art history class, and for example can never remember who is Monet and who is Manet, I enjoyed and learned a lot from Kandel’s history of early abstract art, and art criticism. Kandel focuses on the New York School of Abstract Expressionist painters which includes gestural painters (Kooning and Pollock) and color-field painters (Rothko, Morriss Louis, and Branett Rouman). However, he also includes sections on the artists who started the transition from figuration to abstraction and influenced Abstract Expressionists (Turner, Monet, Kandinsky, Mondrian, Schoenberg) as well as artists who were influenced by them and synthesized abstraction with figurative art (Katz, Warhol, Close, and Sandback). Kandel summarizes each artists stylistic progression, with illustrations. Many artists I knew only from their most famous style and was fascinated to see their other work.

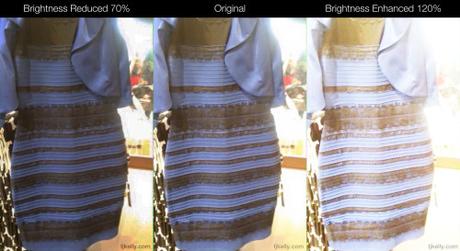

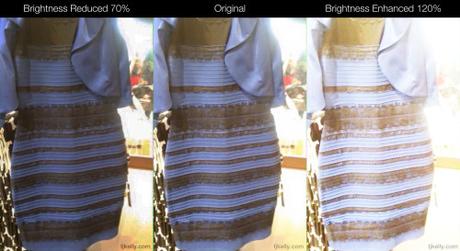

As for the neuroscience, a lot of the basics are similar to an introductory textbook, but it includes more specific material relating to vision and art that I found quite compelling. He even weighs in on whether “the dress” is blue and brown or white and gold—his take: it depends on how we interpret the background of the picture. If we see from the background that the picture is over-exposed we process the dress as blue and brown, but if we don’t look at the background we can process the dress as white and gold. And importantly, after we first interpret the dress, this interpretation feeds back on our visual processing and influences how we subsequently perceive the picture.

“The Dress” (Obviously blue and black by the way :p) Pay attention to the background and note that as the dress becomes white, the background becomes washed out.

“The Dress” (Obviously blue and black by the way :p) Pay attention to the background and note that as the dress becomes white, the background becomes washed out.

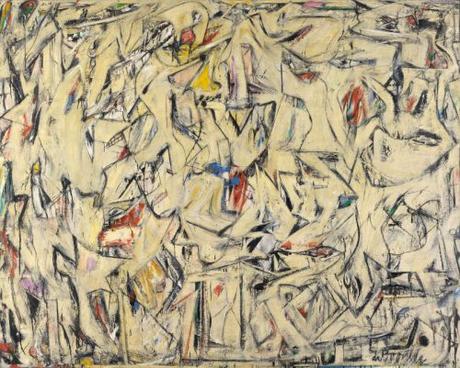

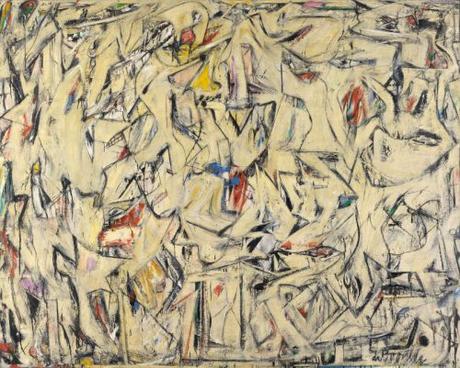

I usually enjoy abstract art, but I’ve always thought of it as a purely aesthetic experience, a kind of visual hedonism devoid of underlying meaning. Kandel notes that abstract art provides a stimuli to our visual system that violates almost all of the rules that the visual system evolved to look for and process. As a result our bottom-up system of processing that looks for lines, figures, perspective, etc. is left struggling and provides the brain with an ambiguous representation, which gives the more conceptual parts of our brain leeway to interpret the art in a variety of ways. Kandel quotes Carl Einstein that abstraction ended “the laziness or fatigue of vision. Seeing had again become an active process.”

Willem de Kooning, Excavation, 1950. I used to look at this picture completely as a a geometric pattern, a work of design and composition. However, Kandel has shown me I can think of it more as a canvas on which to let my imagination run wild. Like looking for faces or images in wood-grain, this painting provides a unique stimulus on which my mind can form connections.

Willem de Kooning, Excavation, 1950. I used to look at this picture completely as a a geometric pattern, a work of design and composition. However, Kandel has shown me I can think of it more as a canvas on which to let my imagination run wild. Like looking for faces or images in wood-grain, this painting provides a unique stimulus on which my mind can form connections.

Despite enjoying it, I have some critiques about the book. Occasionally, Kandel makes bold, unsupported statements about science as if they are self-evident that didn’t ring true to me: “Since all faces have the same number of features—one nose, two eyes, and one mouth—the sensory and motor aspects of emotional signals communicated by the face must be universal, independent of culture.” What?

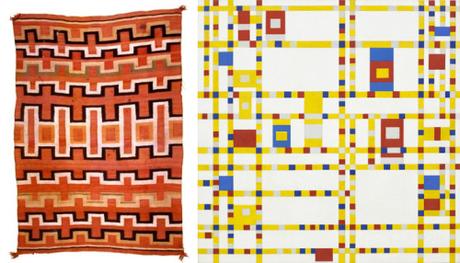

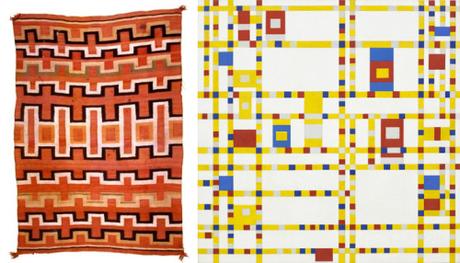

In regards to art, some of his arguments about the novelty of abstract art, seemed a little limited and disingenuous to me that Kandel focuses entirely on western gallery art, and ignores the fact that non-figurative abstract artwork has existed in many cultures for example Navajo art. Similarly, he looks only at artwork from white men, and the only aspect of diversity he addresses is highlighting the contributions of Jewish artists while saying nothing of the religious or cultural backgrounds of any other artists. Also, not specific to this book but many reproductions of art, is that the dimensions of most pieces are not included, so it’s difficult to get a sense of the scale of each piece, and I think the scale of some of these otherwise simple paintings is what makes them feel profound in person.

Left, Navajo Transition Rug, 1880-1885. Right, Piet Mondrian, Broadway Boogie Woogie, 1942-1943.

Left, Navajo Transition Rug, 1880-1885. Right, Piet Mondrian, Broadway Boogie Woogie, 1942-1943.

Finally, I wish Kandel had touched on a final similarity between brain science and abstract expressionism, that they were both substantially funded by the government. While he touches some on the works arts program, he ignores the fact that the CIA insiders have revealed that the CIA funneled money into abstract expressionism as a propaganda tool and countermovement against the communist social realism movement in the USSR.

Overall, if you have an interest in art history, modern art, or visual neuroscience, I think Kandel has a unique perspective and you’ll find this book interesting. And assuming you are not an expert in all three, you’ll definitely come away with a lot of new information. At 190 pages, but full of photographs of artists, paintings, and neuroscience diagrams, Reductionism in Art and Brain Science is a quick read.

Kandel is also the author of the memoir and popular science book about the research that lead to his Nobel: In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind (2007), which I discussed in my recent post on neuroscience books which changed my life. I just learned there is a documentary about him as well with the same title.

He is also the author of another recent book about neuroscience and art: The Age of Insight: The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind, and Brain, from Vienna 1900 to the Present (2012), which I haven’t yet read, but added to my reading list.

I love reading about neuroscience and social science, and I’d love to review more books, so if you’d like me to review a book please comment below or send me an email.

Left, photo of Eric Kandel that I modified using Deep Learning Style Transfer and Chuck Close as a Filter and Photoshop.

Left, photo of Eric Kandel that I modified using Deep Learning Style Transfer and Chuck Close as a Filter and Photoshop. Throughout his carreer, painting prodigy J.M.W. Turner’s style became more abstract. Left, The Shipwreck, 1805. Right, Snowstorm: Steamboat Off a Harbour’s Mouth, 1842.

Throughout his carreer, painting prodigy J.M.W. Turner’s style became more abstract. Left, The Shipwreck, 1805. Right, Snowstorm: Steamboat Off a Harbour’s Mouth, 1842. “The Dress” (Obviously blue and black by the way :p) Pay attention to the background and note that as the dress becomes white, the background becomes washed out.

“The Dress” (Obviously blue and black by the way :p) Pay attention to the background and note that as the dress becomes white, the background becomes washed out. Willem de Kooning, Excavation, 1950. I used to look at this picture completely as a a geometric pattern, a work of design and composition. However, Kandel has shown me I can think of it more as a canvas on which to let my imagination run wild. Like

Willem de Kooning, Excavation, 1950. I used to look at this picture completely as a a geometric pattern, a work of design and composition. However, Kandel has shown me I can think of it more as a canvas on which to let my imagination run wild. Like  Left, Navajo Transition Rug, 1880-1885. Right, Piet Mondrian, Broadway Boogie Woogie, 1942-1943.

Left, Navajo Transition Rug, 1880-1885. Right, Piet Mondrian, Broadway Boogie Woogie, 1942-1943.