Ryota Nonomiya (Masaharu Fukuyama) is a hardworking and successful businessman and engineer, largely absent from the promising development of his six-year-old son Keita (Keita Ninomiya), nurtured daily by his dutiful wife Midori (Machiko Ono). When Ryota and Midori learn that Keita is not their biological son, the result of a switch with another child after birth, they are forced to make a life-changing decision.

Through the hospital they are put in contact with the Saiki family, who own and live above a hardware store. Raised in a different social class, and under very different parenting tactics, the son of Yudai (Rirî Furankî) and Yukari (Yôko Maki), Ryusei (Shôgen Hwang), is very different to the kind, quiet nature of Keita. Not only has Yudai been a present and energetic influence on his growth, but Ryusei also has two younger siblings.

The families are encouraged to switch their children before elementary school, a mere six weeks away. They begin to spend time together and allow the boys to spend weekends at their respective houses in an attempt to acclimatise them into their future living arrangements. But, as expected, the decision is a difficult one, with parents and children individually affected by the unfortunate situation. Can they love a child without their blood the way they did before? Will Ryota choose his true biological son or the boy he has raised as his own?

When the switch is discovered Ryusei's parents immediately think of the damages the hospital will pay, but Ryota, a wealthy man, is more adamant about learning what actually happened. The class status comes up again when Ryota offers, by way of monetary compensation, to take on Ryusei as a second son. This compromise is vehemently rejected by the proud Saiki couple. He is a stern, direct man who would be more comfortable phoning the lawyers on behalf of the families than rolling around in a ball pit with the little ones, as Yudai does.

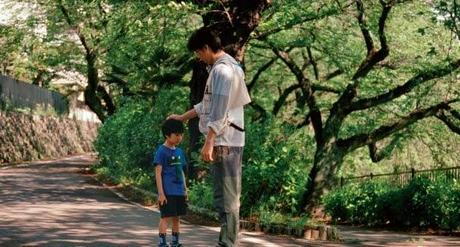

Ryota takes his role as a father seriously, but he's not a great dad. Largely absent, he offers brief compassion in between routine discipline. Even when Ryusei comes to stay, his first paternal interaction is a lesson. When he learns about the switch he raises Keita’s weaknesses and inadequacies, comments that Midori never lets him forget and he grapples guiltily. Keita is not a bit like him – and Ryota believes that this is explained by the fact that he doesn't share his blood - but yet Keita shares Midori’s traits, the person closest to him over the course of his growth. Keita bonds with Yudai, which adds a competitive element to the ‘battle’. Keita doesn’t have the fierce desire to work hard to achieve, but as Ryota discovers, neither does his biological son. The heart of this film is about Ryota accepting that his son perhaps isn’t meant to follow in his footsteps. It is only when he is assigned some leave to spend time with his family that he realizes just how important his presence around the house is.

When Ryota seeks council with his father, he declares that family is in the blood and that they should be promptly exchanged, as many families have done. This decision opposes the wishes of his wife, distraught by the idea of losing Keita, but determined to be the best mother she can be. Yudai and Keita are certainly more lax with their discipline, and have some strange domestic customs, but are content with their limitations and are naturally lovely people. They are unwilling to part with Ryusei, but Ryota and Midori see that they would be worthy caretakers of Keita. While the adults evolve the most over the course of the film, it is the children who ultimately have the say in how this resolves itself.

It is the little moments in Kore-eda's film that hit the hardest. For example, Ryota's comfort as a father begins to shine through when Ryusei declares that he would take his broken remote control car back to Yudai to fix. Initially Ryota was simply going to replace the car (money is the answer, not sharing the project of repair with the boy), but instead he calls Ryusei back in, and tackles the repair.

Every sequence is exquisitely photographed (though the clinically controlled spacing within the frame does seem overly fussy on occasions). The takes are lengthy, capturing every nuance of the genuine interactions and natural behaviours of the characters.

With an unfathomable situation to consider there are some deeply affecting moments in Kore-eda’s film. With a satisfying through-line that effortlessly hops over the common inept dad tropes, this is a beautiful and wonderfully performed examination of the family unit in contemporary Japan.

My Rating: ★★★★