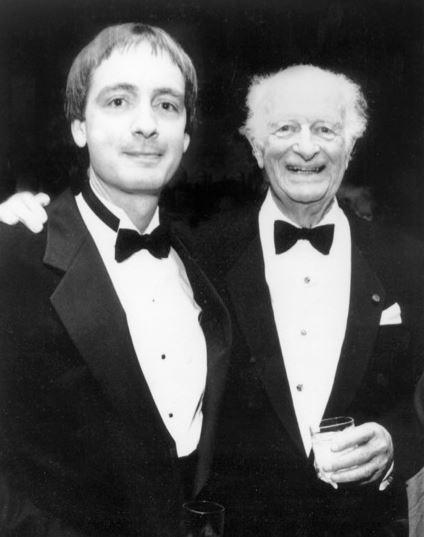

Stephen Lawson and Linus Pauling celebrating at Pauling’s 90th birthday party, 1991

Stephen Lawson and Linus Pauling celebrating at Pauling’s 90th birthday party, 1991By Stephen Lawson

August 19th 1994. Linus Pauling had been ensconced at his ranch on the beautiful coast near Big Sur, California, surrounded by family, for a few weeks, near death from prostate cancer. At the time, I was the chief executive officer of the Linus Pauling Institute of Science and Medicine in Palo Alto and relished a quiet summer evening at home. The telephone rang – Linus Pauling Jr. broke the terrible but expected news that his father had died. Trying to overcome grief, I raced to the Institute to start faxing an obituary that had been prepared months earlier to important news sources – The New York Times, major networks, and other media. Almost immediately the phone lines lit up with reporters asking for more details and comments on Pauling’s life and death. I managed to provide some salient information while struggling with my own strong emotions about Pauling’s death.

Many people who met Pauling or respected and admired him even without having had any personal interaction were also grief stricken. In the following weeks, hundreds of condolences – telegrams, cards, letters, faxes, and phone calls – came to the Institute from around the world. People expressed such sorrow that the great humanitarian who had showed them such courteous kindness had died. They admired his work in science, his never-ending efforts for peace, his championing of vitamin C and other micronutrients, his courage in the face of a hostile US Congress, his patriotic work for the United States during World War II, and his devotion to and love for his wife, Ava Helen.

Pauling connected with people in a way that left many feeling love for him. Of course, he was lauded by luminaries – Francis Crick anointed Pauling the major founder of molecular biology, and Arthur Kornberg noted that Pauling, who had won two Nobel Prizes, deserved another for his discovery of the cause of sickle-cell anemia, the first disease to be characterized as a molecular disease. In 2000, the “Millennium Essay” in Nature – one of the world’s pre-eminent scientific journals – ranked Pauling with Galileo, Da Vinci, Newton, and Einstein, among others, as “one of the great thinkers and visionaries of the millennium” and noted that Pauling was responsible for the “extrapolation from physics to chemistry and the articulation of chemistry as an independent subject” and that “Chemistry, then, is utterly different from physics and biology in its dependence, at a primal level, on just one scientist” – Linus Pauling.

But in the weeks following his death, I was especially impressed by the expressions of sympathy and loss from people who had written to Pauling asking about vitamin C and health problems or other matters and received personal responses, probably often to their surprise. Pauling, who believed that scientists, as experts in their fields, have a social responsibility to explain their work to the public, took time to connect with everyone. As the author of several textbooks, one of which, General Chemistry, educated generations of scientists, and others, including No More War!, Vitamin C and the Common Cold, How to Live Longer and Feel Better, and Cancer and Vitamin C that were written for the lay public and health professionals, Pauling practiced what he strongly advocated.

I first saw Linus Pauling when I was on my way to class in the Quadrangle at Stanford University in Palo Alto. It was a tumultuous era in American history – there were strident demonstrations against the war in Vietnam, and students vigorously promoted free speech rights. As I walked to the Quad, I noticed a gaggle of students and faculty outside the office of Stanford’s president, Richard Lyman. In particular, two elderly men, one of whom was Linus Pauling, were holding signs protesting the firing of H. Bruce Franklin, a political firebrand who had been a tenured professor of English at Stanford and an expert on Herman Melville and science fiction. Stanford had had enough of the turmoil associated with Franklin’s behavior and fired him, an act that Pauling was protesting because tenure supposedly protects the expression of ideas, especially controversial ones. I wasn’t very familiar with the details about the issue, but I certainly admired Pauling’s courage, a quality that defined Pauling’s activism throughout the years. Although Pauling was on the Stanford faculty, he wasn’t teaching undergraduates at the time, so I never had the opportunity to see his celebrated performances in the classroom that had famously inspired legions of students at Caltech.

Years later, when I worked at the Linus Pauling Institute in Menlo Park, Pauling would often stop by my office to exchange greetings, ask me to write for publication, or to help out with experimental studies, which is how I became very interested in vitamin C. Still later, in Palo Alto, Pauling approached me about setting up a laboratory with his quantum chemist colleague Zelek Herman to conduct experiments aimed at producing material that he wanted to support his patent application for a novel method of fabricating superconductors. His goal was to license the invention in order to generate a revenue stream to support orthomolecular research at the Institute. Aided occasionally by Ewan Cameron, Pauling’s medical collaborator on clinical vitamin C studies, we finally succeeded in fabricating the material that Pauling had hoped we would, and Zeke and I went to Pauling’s apartment to show him the samples. It was immensely gratifying to see what joy he expressed, and at that moment I understood how he must have felt every time he made discoveries – understanding something that no one else had understood – throughout his long career.

Pauling lived by an age-old maxim that he humorously amended: “Do unto others 20% better than you would have them do unto you in order to make up for subjective error.” Even in the face of caustic criticism, he remained courteous, usually with his humor intact, and supremely confident – a confidence stemming from his formidable memory and mastery of biology, chemistry, physics, mathematics, mineralogy, and other disciplines. He trusted his own intellect and urged others to do likewise – never simply accept what is said without critical examination.

Pauling had reams of papers on vitamin C that the Institute librarian had acquired at Stanford libraries. In that era, most of the original data was presented in the paper, and Pauling usually checked the statistical analysis that the authors employed, sometimes finding errors that compromised their conclusions. I attended a lecture he gave to a group of biostatisticians at Stanford in the late 1980s in which he discussed the application of the Hardin Jones principle to death rates in clinical studies. He argued that it revealed more information about subcohorts than the standard Kaplan-Meier analysis. There he was, in a room with many of the leading statisticians in the country, and none argued against his thesis. Of course, he was famously wrong about a few things, including the structure of DNA, but sometimes only because he didn’t have access to better data.

Linus Pauling made an indelible impression on everyone who met him, and for them and for those who never had that opportunity, he will continue to serve as a unparalleled model of brilliance, integrity, creativity, and courage – truly a man for the ages.