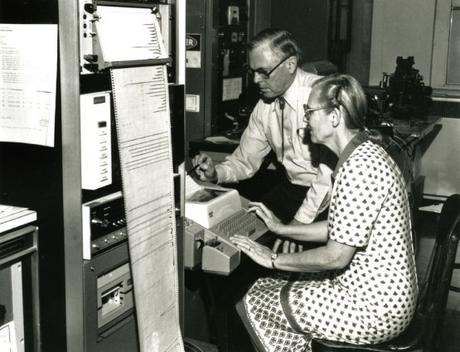

Ken Hedberg, a colleague, and the Hedberg electron diffraction apparatus, 1960.

[Kenneth W. Hedberg (1920-2019) in memorium, part 3 of 5.]

Ken and Lise Hedberg, along with their three-month old son Erik, moved back to Corvallis in January 1956 during a heavy storm. As the couple approached their final destination, Hedberg remembers water reaching almost to the hubcaps of their car. When they finally did make it to Corvallis, the city was largely flooded for the next couple of days.

In a turn of events that fit well with the dreary weather, on Ken’s first day of work at Oregon State College he learned that, in addition to his supervisory responsibilities, he would also be teaching a graduate-level physical chemistry course. The class was scheduled to meet three hours a week and he had been given no time at all to prepare lecture notes. Hedberg ultimately made it through the term, during which he tracked the time that he had spent on teaching-related activities. Including office hours and lesson planning, and found that he averaged 56 hours per week just on his instructional work.

At the same time, Ken was also tasked with getting his research program running. The first step in doing so entailed designing and building an electron diffraction apparatus for which he had received a $30,000 grant. He made an arrangement with the Physics workshop on campus to have the machine constructed, overseeing the process from start to finish. The device took several years to complete, but it worked well and has been used to significant effect for more than fifty-five years. Indeed, Linus Pauling was one of many colleagues from around the world to run samples through the instrument.

When it was built, Hedberg’s gas phase electron diffraction apparatus was state of the art, and during most of his career there were only two laboratories in the U.S. that could perform similar work. As time moved forward and other techniques were developed, gas phase electron diffraction fell out of view for many scientists, thus rendering Hedberg’s lab even more valuable for those who wished to employ the methodology in their advancement of basic science. As a result, Hedberg rarely encountered difficulty in acquiring grant support. His position as a hub for electron diffraction research also led to his making and maintaining a vast number of friendships with scientists across the globe.

The electron diffraction unit that Hedberg built utilizes a nozzle to release gas-phase samples in a stream that runs perpendicular to a vertical beam of electrons. The collision that ensues scatters the electron beam and results in a diffraction pattern that is subsequently recorded on a photographic plate fixed at the bottom of the device. These diffraction patterns are then analyzed to determine specific characteristics of the sample in question. It only takes a few minutes to run a sample, so lots of substances can be run in a day, but the analysis takes much longer — elucidating molecular structures from diffraction patterns is a complicated process.

Another hurdle that Hedberg sometimes faced was transforming particular substances into a gas phase in order to enable this type of analysis in the first place. One notable example was C60, which needs to be heated to 800°C to obtain any kind of vapor. Another instance was N2O4, which degrades to NO2 very rapidly as temperature and pressure increase. Nobody knew for sure if it was even possible to run gas phase electron diffraction analysis on these two substances but, in both instances, Hedberg and his team found a way to create the sample and collect the data.

David and Clara Shoemaker analyzing diffractometer data, 1983

A few months after he had arrived back in Corvallis, Hedberg wrote to Pauling to provide an update on how he was settling in. He reported that, as expected, he and Lise both liked Oregon a lot, and that Erik was growing very fast and had learned a few Norwegian words. He also let Pauling know that his picture was on display in the Memorial Union, one in a series featuring distinguished alumni of the college.

Ken’s correspondence with old Caltech colleagues was certainly not limited to Pauling and, in one particular instance, Hedberg’s connections played a key role in shaping the Chemistry department at Oregon State. When the chair’s position in Chemistry opened up in the late 1960s, Hedberg encouraged his former Caltech office-mate, David Shoemaker, to consider the opportunity. Shoemaker was then on faculty at MIT but he had ties to the west and was open to the idea of returning to that side of the country. He and his wife, Clara Brink Shoemaker, were both distinguished crystallographers, and one of David’s conditions for coming to OSU was that Clara be offered a research position as well.

This condition presented a bit of a problem due to a Depression-era anti-nepotism law that prevented members of the same family from being employed in the same department, except under unusual circumstances. Ken and Lise Hedberg had been able to work together because OSU’s president, Robert MacVicar, good-naturedly regarded a husband-wife scientific team to be an “unusual circumstance.” He allowed the Shoemakers to use the same loophole with one stipulation: officially, Hedberg was to serve as Clara’s supervisor and Shoemaker as Lise’s. This arrangement stood as a running joke between the two couples for several years until the rules were ultimately relaxed.

Three years after he came back to Oregon State, Hedberg was moved into the physical chemistry division of the Chemistry department. With that change, Ken still taught general chemistry and took up new courses in physical chemistry, but was no longer responsible for supervising the department’s graduate teaching assistants. His teaching load remained heavy for a while as he prepared lecture notes for his new classes, but eventually he settled into a more manageable routine. When he finally achieved that balance, Oregon State revealed itself to be a very comfortable place. The Chemistry department was cohesive and friendly, dinner parties and holiday gatherings were common within the faculty, and the competitive divisiveness that often plagues academic units was refreshingly lacking.

Meanwhile, life continued to evolve for Lise as well. During their years together in Pasadena, the Hedbergs had worked as a team on a variety of electron diffraction projects. And although Lise wanted to continue her work at Oregon State, she was unable to for the first few years because she needed to care for young Erik. Their daughter, Anne Katherine – known as Katrina – was born a couple of years after the move to Corvallis, thus further extending Lise’s stay-at-home period.

At long last, when the kids were finally old enough to go to school, Lise would drop them off in the mornings, head over to the university to work in the lab, and then pick them up at the end of the school day. Later, when they were old enough to get to school on their own, she would watch them leave the house and then be home in time to meet them in the afternoons. According to Ken, it took a while for the Hedberg children to realize that their mother worked out of the home, because she was always there when they left and waiting when they got back.

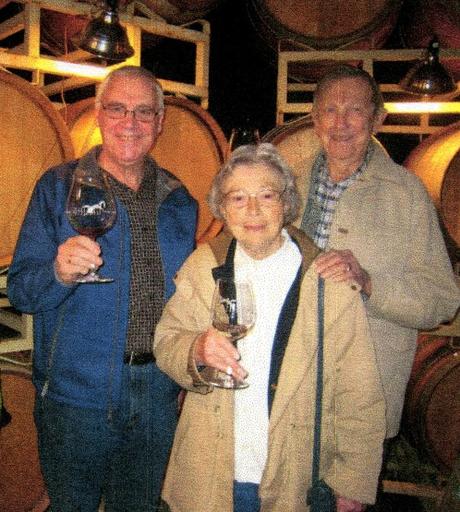

Wine tasting with Kolbjörn Hagen in 2008

In a 2011 oral history interview, Hedberg identified his proudest accomplishment as having overcome his humble beginnings to live a happy, successful life. In offering these reflections, he was quick to point out several moments where small twists of fortune made a dramatic impact on the trajectory of his life. Chief among these was his fateful late fellowship application that ultimately led to him going to Norway instead of Belgium. He mused that if he had submitted the first application on time, he would never have met Lise nor had any of the professional and personal affiliations in Norway that he enjoyed throughout his life.

Indeed, Norway was a critical component of Hedberg’s journey, both personal and scientific. Over the years, the Hedbergs returned to the country numerous times on sabbatical and research trips, and also to visit Lise’s family. The scientific work that they conducted during these visits ultimately led to numerous decorations for Ken. By the end of this life, he had received an honorary degree from the University of Trondheim – offered for “more than 40 years in collaboration with scientists from Japan, Germany, Norway, New Zealand, Great Britain, Hungary, Austria and China” – and been inducted into the Norwegian Academy of Sciences. One one occasion, Hedberg met the Norwegian king at a banquet and spent much of the evening talking with Crown Prince Harald.

Likewise, many of the students with whom he worked in the Oslo and Trondheim electron diffraction labs made their own visits to Corvallis to collaborate with Ken. One of these individuals, Kolbjörn Hagen, emerged as an especially important research colleague, as well as a dear friend.

Collaboration was a fundamental component of Hedberg’s approach to science, and throughout the years his most important scientific colleague was Lise, an expert computer programmer. While Ken took the lead in experimentation and analysis of diffraction patterns, it was Lise who wrote or tweaked many of the programs that the Hedbergs used in their work. In a letter that David Shoemaker wrote to OSU’s Dean of Science, he noted that the Hedberg lab contained a library of computer programs unmatched by any other lab of its kind, due to Lise’s expertise. Shoemaker also wrote that

…Professor Hedberg has more understanding of the nature of chemical bonding in molecules than any other person in the Chemistry Department or on the Oregon State University campus. Perhaps one can even include all of Oregon, except when Linus Pauling is visiting.

The Hedbergs’ son Erik was also handy with computers and often helped his parents manage their programs. The family published two papers together – one by Ken, Lise, and Erik, and one by Ken, Lise, and Katrina – and the authorship shorthand of “Hedberg, Hedberg and Hedberg” was a source of continuing delight for Ken.

In 1983 Ken notified Shoemaker that, after twenty-seven years on faculty, he felt ready to retire, which he did officially in 1987. Hedberg’s primary motivation for this change was to free himself from his teaching burden, but he had no intention of stopping his research.

A few years into his so-called “retirement,” Hedberg wrote to Pauling to provide an update on his life. Amidst news about family, travel and tennis, he noted with glee the enjoyment that he was experiencing in being able to work 12-hour days in his lab. This remained the pattern of Hedberg’s life for another thirty years, a run of time marked by steady grant funding, continuing research, collaboration with faculty colleagues, supervision of graduate students, and mentorship of OSU undergraduates several decades his junior.