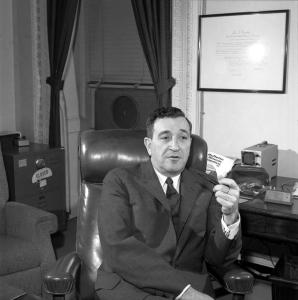

Science Advisor Jerome Wiesner sits in his office, 1 February 1963. Photograph by Cecil Stoughton. Original held in the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

[Marking the one-hundredth anniversary of Jerome Wiesner’s (1915-1994) birth. Post 1 of 2]

On May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy spoke at a joint session of Congress to request funds for sending an American to the moon. During his memorable speech, the president stated his belief “that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.” In an era of heightened patriotism, the president received staggering support from Congress and the people of the United States alike.

Kennedy’s speech was delivered at the height of the Cold War, a time during which the Soviet Union’s own ambitions to explore outer space were making many Americans uncomfortable. For the most part, Americans believed that it was necessary to match and surpass the Soviet Union’s achievements in space in order to secure the United States’ geopolitical power.

In addition to staying ahead of the Soviet Union’s efforts, Kennedy also hinted that there could be additional benefits to the United States’ space program even beyond Cold War positioning. The President went so far as to state that space exploration could very well be “the key to our future on Earth.”

Jerome Wiesner, Joseph McConnell, John F. Kennedy and Harlan Cleveland in the Oval Office. Photograph by Cecil Stoughton. Original held in the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

Kennedy’s remarks added fuel to an already heated debate over the proper relationship between science and federal policy. Following a trend that had begun during the First World War, Cold War scientific efforts had become particularly linked to national defense and, in Kennedy’s words, science had “emerged from a peripheral concern of government to an active partner.”

In 1951, well before Kennedy was known to most Americans, President Harry S. Truman had set up the President’s Science Advisory Committee (PSAC) to provide counsel on issues regarding science and technology. The committee was charged with conveying a refreshed scientific perspective to the top levels of political decision-making, but its members sometimes found themselves in an awkward position if they disagreed with the established views of those in office.

In February 1961 President Kennedy appointed Jerome Wiesner to the PSAC chairmanship. Wiesner was unique among the roster of past committee chairmen in that many of his ideas proved incongruous both with politicians in Washington and with many Americans at large. Of particular importance, and contrary to the President’s optimistic vision for the future of space travel, Wiesner was not at all convinced that sending a man to the moon would yield great advantages for the U.S., be it in terms of technological development or national defense.

Wiesner agreed that sponsoring technological development was a key to the success of the nation. However, he suggested that a more efficient and more effective mechanism for the government to adequately support science and technology was to provide stipends for post-graduate education. A more educated society, Wiesner argued, would be better equipped to meet its own scientific and technological needs.

The Cold War, however, developed within its own unique historical context, one defined in part by widespread anxiety. One outcome of this pervasive fear was an acceleration by which technologies could be advanced. Beginning with the instruments of war developed during World War II – most notably the atomic bombs – the perceived needs of national security propelled the creation of new technologies at a rate never seen before.

The Soviet Union’s launch into orbit of the Sputnik satellite in October 1957 racheted the levels of American cultural insecurity to new heights. With Sputnik, the American public peered into the night sky and literally saw tangible proof that its main enemy had created technologies that would allow it to surveil the country like never before. The seemingly endless possibilities of this breakthrough convinced many that a failure on the part of the U.S. to invest in science and technology would put the nation at grave risk. This fear ultimately created the cultural context by which it proved possible for President Kennedy to allocate an unprecedented amount money for the Apollo Space Program, now estimated to have cost over $170 billion in contemporary U.S. dollars.

Although the President and a significant portion of the American public were convinced that the space program was key to national security, Wiesner and others held firm in their belief that there existed better alternatives for protecting the nation from potential Soviet threat. Nonetheless, as chair of the PSAC, Wiesner was compelled to accept Kennedy’s determination to pursue the moonshot, and continued to advise the chief executive on other issues of science and technology.

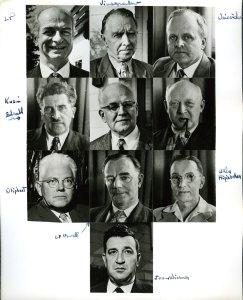

Portraits of participants in the Second Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs, March-April, 1958. Jerome Wiesner is depicted at bottom.

It was at this time that Wiesner turned to an old friend, Linus Pauling, to inquire into the development of his opinions regarding issues of peace and world affairs.

Wiesner was especially interested in receiving Pauling’s counsel on the issue of nuclear testing. Like Pauling, Wiesner was an advocate of a test ban treaty and he wished to use his committee chairmanship to shade President Kennedy thinking in favor of an international agreement of this sort.

Indeed, Wiesner’s unique position gave him powerful influence over federal science policy for the years of his chairmanship, 1961-1963. These years happened to coincide with a period during which Pauling’s main professional focus was his peace activism, and having a strategically placed ally in the White House proved very beneficial to his many causes.

In corresponding with Wiesner, Pauling articulated his argument that the radiation released by nuclear weapons tests was a clear threat to the environment and to human health. Moreover, on a humanitarian level, Pauling felt strongly that the nuclear arms race, if left unchecked, would inevitably lead to new tragedies on the scale of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, if not worse. Through their exchange of letters, Wiesner and Pauling thus built a relationship rooted in discussion of issues that interested them: both believed in nuclear disarmament and both were interested in sharing their scientific and political arguments with broader audiences.

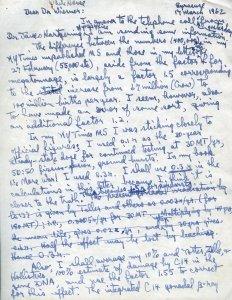

Page one of a handwritten letter from Linus Pauling to Jerome Wiesner, March 17, 1962.

Once his formal involvement with the PSAC concluded (he was relieved of his position not long before Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963) Wiesner became more vocal in his opinions. In 1965 he published a series of essays, titled Where Science and Politics Meet, that were written during his tenure in the White House and that serve as evidence of Wiesner’s strong belief in nuclear disarmament, among other topics. Later, in the 1980s, Wiesner turned to the media and once again laid out his ideas on disarmament in two articles published in The New York Times.

Pauling and Wiesner continued to discuss the issues that they valued through letters and over the phone well into the 1980s. And while they did not ever formally join efforts – each lived on opposite sides of the country – the documentary evidence indicates that they kept one another in mind. At one point, Pauling even nominated him for an award, the Family of Man Award, because he thought of Wiesner as having played a key role in President Kennedy’s signing the partial test ban treaty, an act which directly led to Pauling’s receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1963.

Colleagues and friends for many decades, Linus Pauling and Jerome Wiesner died within months of one another. Pauling passed away on August 19, 1994 and Wiesner died just over two months later, on October 21st.