We love Charlotte, Eric, Cora, and Lyra. They are our friends and our lives are better for having them in it. After Lyra was born, we went with them to the Registro Civil, and acted as the necessary two witnesses who attest to the fact that a) this woman has been pregnant and b) she gave birth in Mexico. It was a typical living-in-Mexico experience, where nothing goes exactly as planned, adventures ensue and a good time is had by all. For our family, this is one of the great benefits of living on a boat in Mexico (as we slowly sail around the world). Learning how to be flexible, how to adjust your expectations, and find the wonder and joy of learning to live in a different culture and speak a new language.

The media, strangers blithering away in online forums, and estranged family members are having a field day tearing down everything the Rebel Heart family has done. I am here to give you a reality check on the assumptions being thrown around and some perspective to help you form a more accurate picture of both Rebel Heart and the cruising community itself. I’m sure you all remember Oscar Wilde’s quote that, “when you assume, you make an ass out of u and me.”

Ass. 1) It is a fundamentally dangerous and bad idea to raise children on boats: The short answer is NO. How do I know this? Well…after a month or so in the hospital NICU, we brought Eli,our two months premature baby boy, who also has Achondroplastic Dwarfism, home to a boat in Morro Bay. It was a 38′ Cross trimaran, made of plywood and fiberglass. We lived out on a mooring, made all of our electricity with a combination of wind and solar power, had a diesel furnace to keep us warm, used an ice chest instead of traditional refrigeration,used a SunShower for bathing, had two beautiful kerosene lanterns for lighting, and no fresh water tanks, so all of our water needed to be ferried out to the boat in 5 gallon jerry cans. Is this a traditional house setup? No. Is it substandard and dangerous, just because it’s different? Of course not. In the morning, before the fog burned off and everything was quiet and still waking up, I’d strap Eli into his Snoopy lifejacket, wedge him upright (facing me) into the bow of my huge Pamlico double kayak (still miss that kayak), and we’d go about our daily chores, picking up fuel, water, ice, and groceries. In the evening, as the ocean horizon swallowed the sun and painted the sky with gold and fire, we’d glide ninja-quiet toward the sandspit, so Eli could throw his arms up and give his small shout, making all the nattering gulls rise up in surprise, like a dark cloud wheeling above our heads. Eli was intimately connected to all the things around him, tuned into the rhythms of the bay, and for a kid who had delayed motor milestones (a normal thing for Achons), this was exactly the kind of rich environment he needed. It’s really tough when your brain is developing faster than your body.

He almost didn’t survive the birth.

Eli in his Snoopy lifejacket.

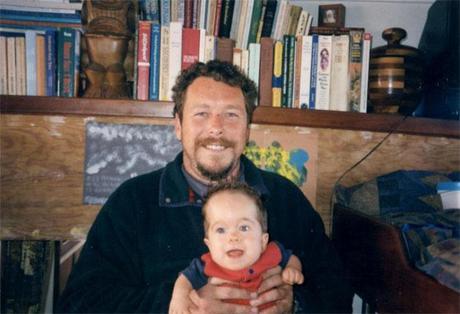

Steve and Eli on our trimaran–you can see how miserable boat life is for babies.

Ass. 2) Boat kids are deprived of social contact: Once again, negatory on that assumption. Boat kids are some of the coolest little people you’ll ever have the pleasure of hanging out with. When we pulled into the La Cruz marina for the first time last year, we ran into a tiny sprite of a girl who was passionate about fishing. She could tell you everything about fish species, lures, and what the success rate was for the techniques she was currently trying. A couple of weeks ago, during a dock party, she says to me, “You know, I don’t think the people who design stanchion mounts have ever actually been on a boat, because if they had, they wouldn’t make them so that they’re always trying to rip your toes off. Especially your baby toe–know what I mean?” And yes, she has an excellent point. My toes know exactly what she means. Then she says, “I’m working on designing a better system and then I think I’m going to send it to those manufacturers, so they can get this right. Because it’s important.” Boat kids learn to successfully interact with adults, other boat kids, and perhaps most importantly, people from other cultures, even when the language barrier is there. Basically, they steamroll right past the barrier and get on with the paramount business of making friends all over the world.

Boat kids make friends fast and do fun stuff, like campouts on the beach.

Boat kids cutting a watermelon in half using only rubber bands.

Eli with Caroline and Meira. Teenage boat kids are obviously learning nothing about socializing.

Ass. 3) On a boat, kids don’t have enough room to properly run around and play: Boat kids do it all. They swim like fish, surf, boogie board, paddle board, kayak, body surf, do yoga, snorkel, go tide pooling, dance, do gymnastics, race bikes, learn to silk dance like you see on Cirque du Soliel, and run around doing regular kid stuff at the local parks or on the beaches. When you’re on a long passage, yeah, it’s hard. They don’t have as much space to run around, but this is a temporary thing that passes in a matter of weeks. When I was a kid growing up in Los Angeles, I remember having Red Smog Alert days, where you weren’t allowed to go outside and play because the smog was so bad it hurt your lungs just to breathe. When Eli was just a couple of months shy of his second birthday, we went down to LA to have his tonsils and adenoids taken out so he could breathe better and he came out of surgery with a tracheostomy. Every day, for 2 and a half years, he had to sit still and have 30 minute breathing treatments 3-4 times a day, on top of the cool mist nebulizer treatments that initially started out 24 hours a day and by the time he got the trach out, had tapered off to only a couple times a day. Roll that around in your head. A two year old, literally anchored to machines, when all he wants to do is run and jump and play. His years of forced inactivity were way more extreme than ocean passages. He’s 17 now and you know what? Everything turned out fine.

Eli pretending to be a monkey while sitting through another endless cool mist treatment.

Ass. 4) It’s only a matter of time before the kids fall overboard and drown: Poppycock. Kids who grow up on boats learn very early on how not to fall overboard. We watch them all the time. We equip our boats with lifelines and even netting to help keep, not just kids, but everyone else, safely on board. On deck they wear lifejackets and even tethers. We teach them to swim. They are always aware of the need to be careful when getting on and off a boat or in and out of a dinghy. This is no different than people teaching their kids not to play in the middle of a busy street. Not to put their hands on a hot stove or pull a pot of boiling water down onto themselves.

Ass. 5) The Kaufmans should pay for the cost of their rescue and they put the lives of their rescuers at risk: Sigh. Are you serious? This is what all the agencies involved in the rescue train to do, all the time, every day. I’m an Ex-Coastie. When we weren’t saving people and their boats, we were training for it, because that is a fundamental part of our mandate. Do taxpayer dollars fund the military? Yes. Guess what? Rebel Heart pays taxes just like everybody else. The boat was in Force 5 wind conditions, which is only about 20 knots. There was no storm. The only person in danger was Lyra, who was quickly stabilized by the Pararescue team.

Ass. 6) Eric and Charlotte were irresponsible because they didn’t have another person to help crew: The first couple of weeks are rough and having another pair of hands on board is really nice, but not a dealbreaker. Are you going to have serious sleep deprivation? Yes. Can you deal with it? Absolutely. After Eli was trached, my job was to keep his airway clear 24/7, without any respite care. No night nurses came to spell us, and night after sleepless night, I had to get up in the morning and do all the things necessary to keep our household running. Steve had to get up every morning and go to work, so we could keep a roof over our heads and food in our bellies. After 2 or 3 weeks, you adjust. You find the groove. Rebel Heart wasn’t out long enough to get their groove, but they were on the verge of it and had they been able to stay out longer, you’d have seen a change in their blog posts–things get easier.

Ass. 7) The kids were too young and Rebel Heart wasn’t prepared for medical emergencies: Adamastor and Sea Raven have babies and they are in the middle of the Puddle Jump right now. In a few days, Fluenta will also join the group and they have, not only a baby, but also two older kids who are elementary school aged. People cross oceans with really young children every year. Both Eric and Charlotte were fully aware of what it would take to safely make this journey. Did they have a well-stocked boat? Yes, it was full to the brim with food and supplies. I know this because a) I was there to see the amazing volume of food they managed to tuck away and b) when they couldn’t stuff any more food aboard, they left us with a dozen or so cans of meat. Thanks guys! As for being medically prepared…Eric has had EMT training and yes, they had all the appropriate antibiotics on board. The family was cleared by a doctor to take this trip. Their medical kit was comprehensive and contained everything you’d expect to find in a first aid kit for isolated journeys. That being said, if your 1 year old is taking oral antibiotics and can’t keep them down, and you can’t give them to her via suppository, then your only other option is going to be an IV, which isn’t something you’d normally have on board.

There are a lot of boat babies out there. Some are crossing oceans and some are hanging out.

Because of his EMT/military/rescue background, Eric was asked to help out with a recent liferaft safety demonstration.

Ass. 8) The boat wasn’t sound or seaworthy enough: A Hans Christian 36 is what we call a blue water cruiser–that means she was built to cross oceans and handle extremely bad weather conditions. Rebel Heart had some mechanical difficulties that are pretty common for a boat that has been sitting in a marina for a couple of months. Could Eric have fixed them? Absolutely. If not for the part where his youngest child became critically ill.

At the end of the day, Eric and Charlotte made the right call, to pop their EPIRB and get help for Lyra as soon as possible. The fact that they lost their boat and their home in the process is heartbreaking, but the important thing is everyone made it back and Lyra is doing well.