Marie Duplessis at the theatre

As should surprise no one, I'm always interested in recovering women's histories from their romanticized legends. Moreover, there are so many layers to the ways in which the character of Marguerite was created and recreated, that -- possibly with professional bias -- I felt eager to read an academic approach to excavating Duplessis' history. The possessions of Marguerite, auctioned in the opening of Dumas' novel, and that of Zeffirelli's Traviata film, are famously based on those of Duplessis. The edition of La Dame aux Camélias I read included a rather sentimental preface, retailing the nineteenth century's fascination with its own romanticized version of Marguerite/Marie's history. Personally, I think Dumas fils and Verdi are both much less sentimental than their reception gives them credit for. On the whole, Weis' work bears testimony to remarkably resourceful research in attempting to create an accurate portrait of Marie, using her own correspondence, the testimonies of contemporaries, and a wealth of detail about the world in which she lived: riding horses, furnishing apartments, and, not least, consuming culture, as a regular attendee of the opera and theatre, and an avid reader. I was fascinated by this vision of an intelligent woman, both sincerely enjoying a variety of pursuits, and crafting, as a demimondaine, an elaborate public persona. The Real Traviata is an impressively researched work; Weis mined multiple archives for diverse sources, and uses Duplessis' laundry lists, library inventories, and shopping receipts take their place alongside her extensive correspondence, and the posthumous narrative sources which are at once challenging and indispensable. The book is available here, for 30% off the list price with this code: AAFLYG6While consistently interesting, and scrupulously researched, the book seemed somewhat inconsistent to me in tone. On more than one occasion, Marie is described as wielding the "power of her sexuality" over men. What about enjoying her sexuality for its own sake? Or making a strategic choice to obtain more financial security as a courtesan than could be hers as a laundress or a milliner? (She tried her hand at both of these demanding and highly gendered professions upon arriving in Paris.) Weis acknowledges the gravity of the offenses against Marie, but can't seem to free himself from a distanced, somewhat patronizing tone concerning her role as a courtesan. It's a jarring note in a book that's dedicated to -- among other things -- examining the social hypocrisies surrounding Duplessis' history and mythologizing. Perhaps few women read the proofs. The further I got into the book, the more puzzling I found the occasional vocabulary of "sin and luxury" (sic! elsewhere "sin and decadence") imported, as it seemed, from the voyeuristic vocabulary of an earlier time. This tendency to veer towards the sentimental or disapproving is pointed up by the book's own content, which presents a much more nuanced picture of Marie than the cliché of the repentant Magdalene, and also provides, often in damning terms, a vivid portrait of the close and often exploitative circles in which she moved. Many of her letters having been burned, Marie's character is revealed--insofar as it can be--through her actions. Weis gives a portrait of a vivacious woman who was at the epicenter of elite Paris' social life and the scandals thereof, but who also cultivated ties with her family and close friendships with other women... and who did, like her operatic avatar, give generously to the poor.

The Real Traviata assumes in the reader a great appetite for historical detail. I appreciate this! Do I want to see photographs of the houses where Duplessis stayed? Do I want to know about how her first wealthy lover made his fortune? Do I want to hear about the 1840s geography of Paris's cafés and boulevards and opera houses? the circulation of international elites between Paris and the racecourses and spa towns of Europe? Absolutely, on all counts. I might be one of very few readers likely to want more footnotes (or endnotes) but I feel they might have improved the clarity of the narrative in places, streamlining the main text to give the eventual conclusions reached alongside the evidence supporting Weis' reasoning. Still, Weis' style is lucid, striking a nice balance between the academic and the conversational. In reconstructing and contextualizing the circumstances of Marie's entry into the career of a freelance courtesan, Weis makes use of contemporary social and medical research into sex work, sexually transmitted infections, and the sexual exploitation of young women and girls. It's disturbing reading, of course, and also valuable in providing context for what Marie's options were... and how the demimonde she entered was viewed by those outside it. I appreciated that Weis used the memoirs of Céleste Mogador, as well, alongside letters from noblewomen and artists, to give the perspectives of other women astutely maneuvering in Marie's dangerous world.

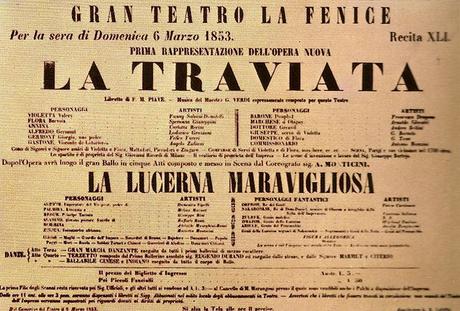

Playbill from La Traviata's premiere

Approximately the last third of the book is devoted to Marie's posthumous artistic incarnations, with a chapter on the genesis of La Traviata, and another on its performance history. I was particularly fascinated by the revelations of just how intricately related the social world of Marie Duplessis was to those who would create, perform, and consume the works of art based on her life. Not only was she (famously) the lover of Dumas fils, but she was friends with one of the first actresses to star in La Dame aux Camélias, and attended some of the same Parisian salons as Verdi and Strepponi. Even more unpacking of how these complex relationships influenced the reception of La Dame aux Camélias and La Traviata might have been interesting. In his discussion of La Traviata's performance history, Weis helpfully punctures some longstanding myths surrounding the opera's premiere, e.g. the inferiority of the soprano. Comparison of the 1853 and 1854 versions of the score is similarly interesting. I found his discussion of the production history, however, baffling (not to say infuriating.) Verdi's famous insistence on the use of contemporary costumes, and satire of social hypocrisy, appears alongside praise of the work's "poetic period aura" and condemnation of Konwitschny and Decker for featuring "sluttish Violettas" (sic!) A point, it would seem, is being not so much missed as pointedly ignored. Such bizarre internal contradictions mar a work that is generally lucid, pleasingly packed with anecdote, and enriched with a variety of images, from photographs to portraits to playbills. There's trenchant irony, it seems to me, in this tension between half-prurient disapproval and devout adoration in a biography of a woman who, in her brief life, inspired so much of both.