"So what you need is a complete harmony of your technique of movement on stage, and the expression of your interpretation, with the music, and with the pure singing itself. This isn't easy, Lord knows, but if you get a singer who has command of all of that, then you get a sort of miracle, like Maria Callas. I don't think I ever succeeded in putting all this together. Maybe with Dorabella, or the Dyer's Wife. But that decision lies with the audience."

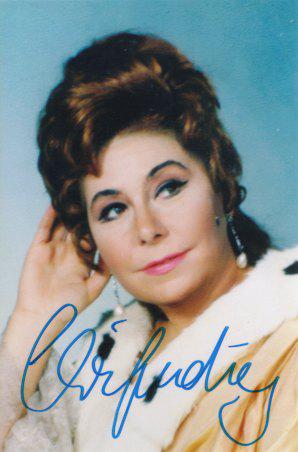

Well, Gentle Readers, I have returned from a week of sand and sun and reading about opera instead of about medieval history. The first entry in this blog's summer reading list is, perhaps unsurprisingly, the memoir of Favorite Mezzo, Christa Ludwig. Definitely the Opera has organized her own (hopefully continuing) series around the question of Should You Read This Diva's Memoir. I have several answers for you, Gentle Readers! If, like me, you think Christa Ludwig is pretty fabulous, the answer is a resounding "Yes!" If you want a biography neatly organized into thematic chapters in chronological order, you might find it frustrating. But if you are intrigued, or even elated, by the prospect of an idiosyncratic narrative, give it a try. The first part of the book, indeed, is mostly chronological; but then it takes flight. We get descriptions of Ludwig's relationships with, opinions on, and reminiscences about, various conductors; a mini-essay on what makes a prima donna; descriptions of a healthy handful of her roles, and her relationships to and opinions on them; questions of interpretation; thoughts on travel, superstition, knitting, marriage, studio recordings, opera houses around the world... you get the idea. For me, at any rate, the tone makes it reminiscent of sitting in an aunt's living room, drinking her coffee while she shares stories.

Throughout, the frankness of Ludwig's manner is disarming, and not infrequently disconcerting. After the first chapter, which is both a description and a send-up of her writing process, I thought I might never get through the book, given the amount of time spent giggling helplessly. If you're reading this to beguile hours on a beach, or in a similarly carefree frame of mind, you may be tempted to skim through the sections on childhood and adolescence, not because of dullness, but because wartime is grim. Ludwig doesn't shirk from descriptions of tragedy, need, and "Lohengrin-Leberwurst" (nie sollst du mich befragen...). She sewed her own recital dresses for the early part of her career... and the earliest of these was a red sheath with black-and-white puffed sleeves, crafted from a torn-down swastika flag, in which she sang cabaret (!) for occupying troops. The reader is back on more expected territory with early engagements; she praises the creativity of the opera director who created productions for Frankfurt's stock exchange (the opera house was, "of course," bombed out.) On her own artistic development she remarks: "When I think that Grace Bumbry was singing Venus at Bayreuth [in her late twenties]! I was still a provincial goose at that age!" Ludwig comes across as (justifiably) proud of her accomplishments, but never complacent about the often-difficult process of her training and development. Nor is she shy about self-criticism. A particular gem: "I had no technique then, so of course I always squawked on the high notes..."

The central section of the book is devoted to characters on and off the opera stage. The conductors begin with Karl Böhm, whom she describes as her "spiritual father," and writes about with commensurate affection. She reports their first conversation as follows: "So, my dear [mein liebes Kind], you want to audition for me for the Wiener Staatsoper?" "No, no no, I don't want to at all! I'm too young! I don't think I'm ready!" "Well, I'll just see about that." An aside characteristic of the book is Ludwig's remark on Böhm's tempi: "It was not without reason (though it was a little mean of him) that Karajan gave him the most accurate watch in the world for a 75th birthday present." About Karajan himself Ludwig writes with great respect for his musicality, and manifest affection, but also with a hilariously wry take on his (in)famous image creation. Her warm affection for Bernstein overflows, and she writes about singing the Marschallin under his baton, and demonstrating 3/4 time for a Young People's Concert, with equal enthusiasm. Another fascinating aside: "Without Gustav Mahler under Bernstein, I don't think I'd ever have been able to craft Schubert's 'Winterreise.' "

The central section of the book is devoted to characters on and off the opera stage. The conductors begin with Karl Böhm, whom she describes as her "spiritual father," and writes about with commensurate affection. She reports their first conversation as follows: "So, my dear [mein liebes Kind], you want to audition for me for the Wiener Staatsoper?" "No, no no, I don't want to at all! I'm too young! I don't think I'm ready!" "Well, I'll just see about that." An aside characteristic of the book is Ludwig's remark on Böhm's tempi: "It was not without reason (though it was a little mean of him) that Karajan gave him the most accurate watch in the world for a 75th birthday present." About Karajan himself Ludwig writes with great respect for his musicality, and manifest affection, but also with a hilariously wry take on his (in)famous image creation. Her warm affection for Bernstein overflows, and she writes about singing the Marschallin under his baton, and demonstrating 3/4 time for a Young People's Concert, with equal enthusiasm. Another fascinating aside: "Without Gustav Mahler under Bernstein, I don't think I'd ever have been able to craft Schubert's 'Winterreise.' "At least as much fun as Ludwig's chatty reminiscing about her fellow artists, for me, are her reflections on the process of creating the characters who must live on the stage. With Carmen she had difficulties, describing herself as "the anti-type of a Carmen, really..." and the first two productions she did not feel as a success. So when the offer of a new production with Schenk in Vienna came...: " 'Listen, Otti, I'm not small and delicate. I have a round face and a snub nose.' The exterior does have to be considered to make a character believable! ...So I didn't swing my hips, didn't have to be a man-eating vamp, didn't have costumes from a travel brochure. I was just a girl from the lower classes, a poor factory worker who goes her own way, impudent and fearless..." Although she bemoans the physical difficulties of playing trouser roles, her section on them contains one of my favorite quotes from the book: "Once there was a reading of Rosenkavalier, with a young man as Octavian... and there was nothing! After all, the charm is in the piquant situation that the lovers are really two women." (Thank you, Christa Ludwig.) Like Beethoven himself, she describes Fidelio as her Sorgenkind. "Reviewers always notice that the Leonore is more relaxed in the second half. What, they think we aren't scared of that impossible aria?"

As a reader, I was more conscious of the "untold" in the sections of the book where Ludwig discusses more of her familial relations. Frankness prevails, but the tone struck me as slightly more reserved, words a bit more carefully chosen. (The tone that prevails for chronicling how she met and fell in love with her current husband, however, is one of burbling, irrepressible delight.) The conversational tone of the book is reinforced by the constant presence of mentioning people or issues which have their own sections whenever they happen to be associated with the current topic. Philosophical asides are studded with quotations from Rilke, Hesse, and opera libretti. The book is not devoid of the human capacity for self-contradiction. At one point, early on, Ludwig states that the audience is incapable of forming musical judgments (ouch!) but this turns out to be a very narrowly limited statement of limitation. The discussion of communication with the audience, and the audience's capability of assessing--not only sensing--the musical and dramatic power of a performance, is a theme of the book. A similar contrast appears between her early dismissal of the women's lib movement (the point of which was to state that the "freedom" of a career was a lot of work, but still, idol of my heart, how could you?) and a mordant critique of gender-biased attitudes towards the spouses of singers ("Poor things," says Frau Ludwig, "I pity them all.") Another such curious tension appears in the closing of the book: a dialog constructed between Christa Ludwig and her voice, a bittersweet confection of three pages. The grateful reader/listener may be gratified to know that, in the end, they agree that the hard work was worth it. The very last word, though, is given to Strauss, and the text of "Morgen." And here is a performance of that from last year's Salzburg Festival, with Ludwig reading from the Marschallin's monolog (if anyone knows more about the performance from which this is taken, please do let me know):