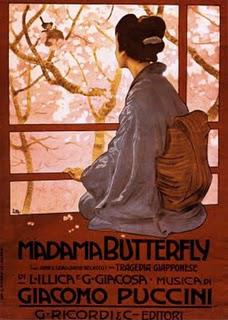

The opera is Cio-Cio-San's. I for one don't care what happens to [insert choice epithet] Pinkerton. But there remains the boy: "Tu, tu, piccolo iddio!" The jacket of Angela Davis-Gardner's novel, Butterfly's Child, promises to answer the niggling question of what happened next. The synopsis of the opera given at the front of the book indicates that it's not just intended for enthusiasts. The enthusiastic blurbs by other novelists promised that it was a page-turner, and this I certainly found it to be. A central thread of it is also a Bildungsroman trajectory for Benji, Butterfly's son, taken to live with Pinkerton and Kate. But the relationship of the novel to the opera is not as straightforward as it seems at first.

The opera is Cio-Cio-San's. I for one don't care what happens to [insert choice epithet] Pinkerton. But there remains the boy: "Tu, tu, piccolo iddio!" The jacket of Angela Davis-Gardner's novel, Butterfly's Child, promises to answer the niggling question of what happened next. The synopsis of the opera given at the front of the book indicates that it's not just intended for enthusiasts. The enthusiastic blurbs by other novelists promised that it was a page-turner, and this I certainly found it to be. A central thread of it is also a Bildungsroman trajectory for Benji, Butterfly's son, taken to live with Pinkerton and Kate. But the relationship of the novel to the opera is not as straightforward as it seems at first.The sections of the novel which I found most successfully realized were those concerning Benji's early childhood. I thought Davis-Gardner traced his process of coming to terms with his environment sensitively and with a vital touch of humor. And she does paint the environment, the American Midwest in the early twentieth century, very well; I very much enjoyed the descriptions of the weather, the changing seasons, the flora and fauna of Pinkerton's Illinois farm. The protagonists and antagonists in the drama of Benji's acceptance in the community are divided more clearly into camps than seems perfectly natural, but the characters are deftly drawn. Nor is Benji the only protagonist. In addition to a schoolteacher, a veterinarian, and Pinkerton's rather formidable mother, we have Pinkerton (who goes by Frank in the novel) and Kate themselves. In brief: Pinkerton is a sorry specimen, and long-suffering Kate is sympathetic, but I thought they were the most complex characters in the book. The eternal question of "Just how terrible a person is Pinkerton?" is brought up for consideration. And Kate, for whom I rooted staunchly, is a fascinating creature: deeply religious, very sensitive, and fiercely intelligent.

Contrary, I fear, to the author's intentions, I was very sorry to leave the Pinkerton farm behind when Benji inevitably struck out to find a guide to his past and future in Japan. Maybe the evocation of Nagasaki's sights and smells, its harbor and noodle shops, flowering trees and tiled roofs, would be more gripping to me if I had visited Japan, and had some sense of the original. Also--and this might be my chief critique of the novel--I began to suffer from having my sympathies so often called on. Does everyone have to have a tortured past? Ill-fated love affairs? Hardship of weather and economic circumstances? I'm not saying that it's unrealistic; but as a reader, I would have appreciated a more selective emphasis. The ways in which Puccini's opera becomes entwined with the novel as a work of art, as well as its "understood" premise, are fascinating, but affect the denouement to strongly to be discussed in detail. Handling Puccini in this double sense is of course tricky. I thought it was handled well, but I found it more intriguing than satisfying, due more to my feelings about the opera than about the prose. Should you read this book? To write such a work inevitably invites comparisons with the superb artistry and sheer emotional wallop of Puccini's opera; equally inevitably, it suffers by the comparison. Still, it makes a good read for the weekend or the beach.