Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House. Photo: Royal Collection.

Like many other people, I have a passion for miniature things – there’s just something so delightful about looking at tiny versions of everyday items and, oddly enough, the more humdrum the item is, the more magical it appears when miniaturised.

Annoyingly, I don’t have a doll’s house of my own any more (my children would destroy it in seconds) but if I did then I would definitely take Queen Mary’s dolls’ house, which is on permanent display at Windsor Castle as my model of how a dolls’ house really ought to look, although, of course, we can’t all get Lutyens in to design one for us.

Queen Mary’s dolls’ house was dreamt up by her childhood friend and cousin of her husband, Princess Marie Louise of Schleswig-Holstein, the youngest daughter of Princess Helena and grand-daughter of Queen Victoria. After the annulment of her marriage, Marie Louise had returned to her family at Cumberland Lodge in Windsor Great Park and was in the custom of spending a great deal of time with George V and Queen Mary. It was during one of these visits, at Easter 1921, that she decided to commission a wonderful dolls’ house as a present for Queen Mary, who had an absolute passion for miniature objects.

Being of an artistic and literary bent, Marie Louise immediately set to work floating the idea around her circle of arty friends, many of whom were amongst the best known artists of the age but her biggest coup was getting the wonderful architect Sir Edwin Lutyens on board after approaching him with her idea at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition. Luckily for us all, Lutyens was not at all stuffy and was instantly enraptured by the idea which appealed immensely to his own childlike sense of fun (exemplified by his making the banisters of the crypt stairs at his never to be completed Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King suitable for the choirboys to slide down them).

The upper hall. Photo: Royal Collection.

Lutyens immediately and with great enthusiasm set to work drawing up plans for what was to be an elegant, harmonious and yet still very grand miniature house. He was aided in this by his friends, most notably the celebrated gardener Miss Gertrude Jekyll, who designed the small garden for the house, which a teeny birds nest, birds, a snail and colourful butterflies. The plans were also given an immense boost when Sir Herbert Morgan, President of the Society of Industrial Artists got involved, seeing in the dolls’ house an opportunity to show case British craftsmanship at the upcoming British Empire Exhibition at Wembley Park in 1924. His involvement ensured an even wider amount of external help and interest in the scheme and eventually a Committee was formed to formally oversee the project with Princess Marie Louise taking on the rôle of intermediary between the committee and Queen Mary, who was completely thrilled and excited by the whole thing.

The house took around three years to put together, with the majority of its contents being custom made to a one inch to a foot scale. A team of around 1,500 craftsmen and artists worked on the building with most of the furnishings copied or at least inspired by originals in the royal collections and those at stately homes like Knole and Harewood House as well as scaled down copies of the royal dining services, paintings in the royal collections and so on. Everything was done with almost military precision as artists worked on the intricate ceiling designs, others carefully laid the marble, mother of pearl and wooden parquet floors and Lady Jekyll, Gertrude Jekyll’s sister-in-law, took charge of stocking up the miniature kitchen and larders with tiny provisions provided by companies like Frys, Tiptree jam and McVitie.

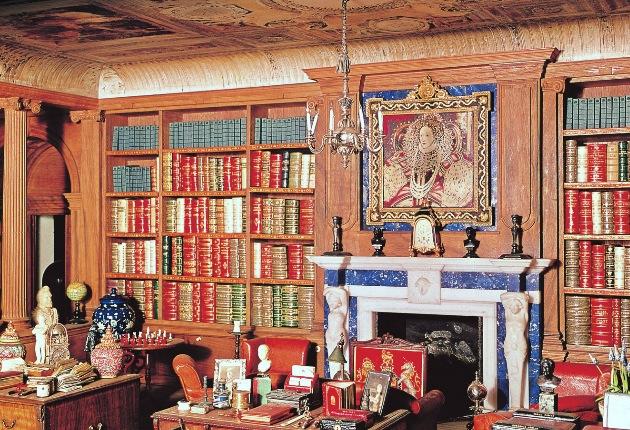

The library. Photo: Royal Collection.

Each room was designed and then decorated with an impeccable attention to detail – the basic premise being to create an opulent yet comfortable residence fit for a King and Queen, furnished with all the finest and most luxurious items that the era could provide. Typically of Lutyens there are also some humorous comical touches amongst the eye popping grandeur – a tiny insurance policy is locked inside the safe in the library for instance.

As you might expect, it is the library of Queen Mary’s dolls house that I find most fascinating. This was Princess Marie Louise’s personal project when the house was being put together and she took great pleasure in commissioning books and art work from well known contemporary artists and writers for the room. There are three hundred tiny books in the library, all specially made and bound for the room and including a Koran, the complete works of Shakespeare, a dictionary and three Bibles as well as works by Sir James Barrie, Thomas Hardy, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (who contributed a Sherlock Holmes short story), Rudyard Kipling, Hilaire Belloc, Siegfried Sassoon, M.R. James and H. Rider Haggard. In fact the only writer to refuse and ‘in a very rude manner’ to contribute his work was George Bernard Shaw. What a misery guts.

The library also contains seven hundred tiny paintings by well known artists of the period, many of whom were members of the Royal Academy such as Dame Laura Knight, Sir William Nicholson, Munnings and Sir William Russell Flint, their works being stored in small folios in special cabinets. There are also musical scores by well known contemporary composers such as Gustav Holst with Elgar being the most notable exception – like Bernard Shaw he sent the committee a very rudely worded refusal to participate, claiming that the royal couple were ‘incapable of appreciating anything artistic’.

The saloon. Photo: Royal Collection.

The completed house was revealed to the press in February 1924 and then unveiled to the public in April when it went on display at Wembley. It’s estimated that during the seven months that it was on display it was seen by around 1,617,556 people, most of whom were surely utterly spellbound by it. We know for certain that Queen Mary, whose present had grown to extraordinary proportions, absolutely adored the house and spent hours on end arranging the furniture and playing with everything inside.

The house itself is clearly based on the Banqueting House in London, which is pretty much all that remains of the magnificent Whitehall Palace and which has a distinctive Inigo Jones design, based on the palaces of Italy, with rustication at ground level and a harmonious range of columns across the front.

The entrance hall. Photo: Royal Collection.

While the outside is classically formal, the inside is bright and spacious with a very grand entrance hall and beautifully designed Lutyens staircase (just look at that sweep from the hall) forming the heart of the house. The floor of the entrance hall is made from squares and diamonds of white marble and lapus lazuli, while the silver balustrade is based on that at Hampton Court. There’s also a beautiful silver and enamel Cartier clock in the entrance, one of seven made by the firm for the house.

Along from the entrance hall is a graceful white and gilt dining room, which overlooks the garden designed by Gertrude Jekyll. The walls are hung with beautiful paintings include three by Munnings, which are copies of his own works. There’s also a lovely copy by McEvoy of the famous Winterhalter portrait of Victoria, Albert and their four eldest children. The room’s décor is eighteenth century in influence, set off with a replica Aubusson carpet; Cartier red lacquer screen; linen tablecloth woven with miniature Garter stars, thistles and shamrocks and based on the ones used at Buckingham Palace and a lavish silver dinner service provided by the Crown jeweller Garrard, which cost Sir Herbert Morgan £280.

The dining room. Photo: Royal Collection.

Also on the ground floor are the fascinating service rooms – the kitchen and various sculleries and store rooms that were so lavishly equipped by Lady Jekyll with miniature versions of all the best foodstuffs of the period such as Colman’s mustard and Cooper’s marmalade as well as many of the latest modern conveniences all scaled down for ‘use’ within the house. I adore the kitchen with its scrubbed wooden table, earthenware bowls, range cooker and, most importantly, tiny cat and ivory mice captured within a tiny wire humane trap. It provides a perfect glimpse, albeit in scaled down form, into a functioning kitchen of the period, half tiled with a parquet wooden floor, cheerful dresser laden with Doulton crockery against one wall and a pervasive atmosphere of well scrubbed, cheerful cleanliness.

The servery and butler’s pantry beyond are both well stocked with china, glassware and even a tiny cocktail shaker as well as complete sets for serving coffee, dinner and breakfast. While beyond is the strong room, where the silver dinner service and gold bowls are kept safe along with miniature replica copies of the crown jewels, complete with real diamonds.

The kitchen. Photo: Royal Collection.

Upstairs there is the Saloon, a graceful space that was clearly designed for entertaining and follows the same eighteenth century aesthetic as the dining room with delicate, spindly legged chairs, beautiful shimmering gold embossed wallpaper and even a gorgeous little grand piano, all set off by a collection of miniature royal portraits. As with the other rooms, it is the small details that make this so exquisite – teeny tiny photographs on tables, books left on chairs as if the reader has been interrupted, a tiny basket of fruit.

Along with the saloon, there are apartments for both King and Queen on the first floor. The Queen’s apartments are extremely luxurious with ivory painted walls, gilt ornamentation and more than a hint of 1920s glamour about them. There is a wardrobe that would inspire even Carrie Bradshaw with envy, inspired by the aisle of St Paul’s Cathedral, lined with clothes cupboards and with a tiny Chubb safe intended for jewels. Next door is the large and very opulent bedroom with pale taupe silk damask walls (originally pale blue but they have faded over time) and matching bed hangings. It’s absolutely gorgeous, with my favourite touch being the beautiful old fashioned dressing table in the centre of the room with its glass and enamel accessories.

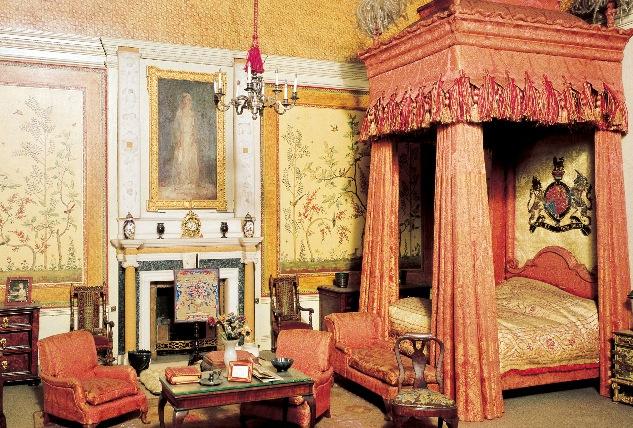

The Queen’s bedchamber. Photo: Royal Collection.

Also fabulous is the bathroom next door which has mother of pearl floor tiles, an alabaster bath and basin and exquisite shimmering ivory shagreen on the walls. There’s painted mermaids frolicking on the ceiling and real scented toiletries all ready to be used by the house’s doll residents.

The King’s rooms are next door and are rather different with a more cosy, quintessentially ‘English’ masculinity in their design, with the bedroom in particular being rather lovely with its soft peach bedhangings on the stately Lutyens designed bed, walls painted to resemble Chinoiserie wallpaper and comfortable furnishings. There’s also a lovely ceiling painted by George Plank with a flower covered trellis that is actually a musical stave with the national anthem picked out in flowers.

The King’s bedchamber. Photo: Royal Collection.

The bathroom next door is white and grey with dozens of miniature prints from Punch on the walls and tiny toiletries all laid out ready for use, including a toothbrush with bristles taken from the inside of goats’ ears, which isn’t nice at all though.

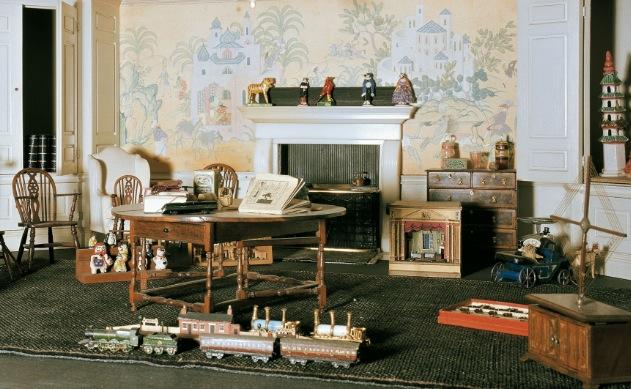

Upstairs there is a fabulous linen room with piles of exquisitely monogramed hand sewn sheets, table cloths and towels, staff bedrooms, a charming room for the Princess Royal, a comfortable Chinese inspired private sitting room for the Queen and a simple night nursery with a gorgeous ivory and applewood cot for the baby as well as miniature rusks, vaseline and a 2.54 cm long bottle for milk. Next door there is a fabulous day nursery replete with every toy that a 1920s upper crust child could possibly want – toy soldiers, hobby horse, train set, a piano and Winsor & Newton paint set. There’s also a very contemporary touch with the excellent and rather stately gramophone, which is in full working order and comes complete with a set of tiny recordings of such patriotic classics as God Save the King and Rule Britannia.

The nursery. Photo: Royal Collection.

The upstairs rooms may be of less interest aesthetically to the more luxurious and ornate ones downstairs but they are perhaps even more fascinating as they give a fantastic glimpse into life behind the scenes of an immense upper class household in the 1920s complete with laundry baskets, bottles of Vim, mops, Singer sewing machines and even an upright Hoover vacuum cleaner.

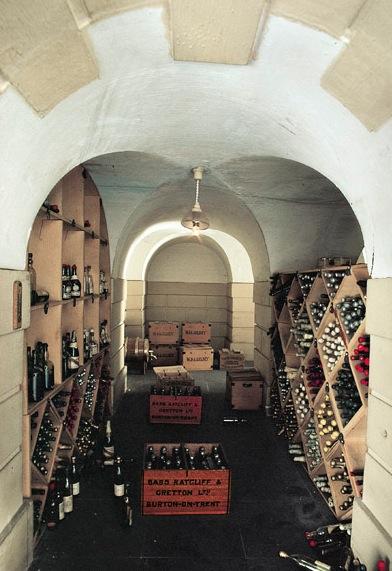

The wine cellar. Photo: Royal Collection.

Equally fascinating is the cellar beneath the house, which is well stocked with bottles of wine supplied by Berry Bros of St James’, who provided a huge selection of vintages all contained in handblown glass bottles with tiny labels. If wine isn’t your thing then there’s also bottles and casks of Bass beer. It would be the height of decadence, I think, to attempt to get drunk from the contents of Queen Mary’s cellar, emptying one tiny bottle after another into your mouth.

And if wine isn’t your thing then perhaps the garage would be – it’s stocked with six fabulous cars, supplied by Daimler, Sunbeam, Vauxhall, Lanchester and Rolls-Royce and painted in the royal livery colours of black and scarlet. There’s even a Rudge motorbike with sidecar, a fire engine and their own petrol pumps and equipment.

The garage. Photo: Royal Collection.

Of course, the house was never really designed to be played with and despite its name there are no dolls within. It’s there to be looked at, admired and appreciated as a work of art in its own right.