Some Background on the Ball Supper in the BBC2 Documentary

Although the silver and other tableware here is accurate for the period, this is more of an 'evocation', than a recreation of the Netherfield ball supper. But hopefully it does offer some insight into the sophistication of dining in the Regency period. Photo by Andrew Hayes Watkins. ©Optomen Television

Those of you who regularly read this blog will know that I am frequently rather harsh about the lack of accuracy in food and table settings in period movies and television dramas. Rarely have I seen any recreations of this kind that have really impressed me. Though of course I constantly have to remind myself that these productions are not pretending to be anything more than dramatised settings of fiction, so the food and table setup are props for the cast to perform around. Therefore I suppose it is a bit sad of me to look for detailed historical accuracy in such fictional contexts. However, when the format of the production is a documentary, a medium which attempts a true reflection of reality, it is a different matter. On British television in recent years, there have been a number of documentaries which have attempted to examine the history of our food. In most cases these recreations have been worse than those in the period dramas. I am not going to give any examples, but some of these productions have been wasted opportunities and I have frequently been embarrassed of my own involvement in them when I see the final edit. I believe that a more intelligent approach to food in history has the potential for really exciting - and yes, even more entertaining television than risk averse commissioning editors realize.So how, you might ask, can this sort of thing be done in a more revelatory way? Well the first essential factor is to work with a production team who really listen and understand these issues. When I was first invited to create the food and table for BBC2's documentary Pride and Prejudice Having a Ball, I had an exploratory meeting with the producer/director Ian Denyer. For the first time in my long career, I found myself talking to a television professional who was singing from the same hymn sheet as myself. Ian and his colleague Sarah Durdin Robertson were really keen to portray the same level of historical accuracy that I aim for in my museum exhibitions in their production. They too wanted to avoid the tabloid 'Carry on Banqueting' approach that has too often been the standard approach when it comes to the treatment of food history on television.

Confections from the Netherfield dessert - all designed for consuming with sweet wines. The Prince of Wales biscuits in the foreground, emblazoned with the iconic feathers emblem of the Regent, were made from Joseph Bell's 1817 recipe. The pink sweets are Pistachio Prawlongs from Frederick Nutt's 1789 The Complete Confectioner, a key work of this period. The plate in the background contains spice biscuits, wafers, sweetmeat biscuits, toad in a hole biscuits, millefruit biscuits and filbert biscuits, all also made from Nutt's recipes.

Ian told me the aim of the programme was to recreate the Netherfield ball from Jane Austen's 1813 novel Pride and Prejudice, including the production and serving of the ball supper, which would be my job. In her beautifully measured, but succinct prose, the author offers just a few clues about the nature of this meal, leaving much to the reader's imagination. But if our twenty-first imaginations have been nourished by cliché-ridden, stereotypical concepts of what food and dining was like in the late Georgian period, how can a modern reader visualise such an occasion? Austen tells us it was a sit down affair, with the celebrated 'white soup', but says little else about the nature of the food that was served. So if we were to accurately recreate a Regency ball supper, where should we look for research material? There are certainly many contemporary reports of grand balls in the newspapers of this period in which suppers are described, though hardly ever in any significant detail. One thing we do learn from these sources is that the supper was usually served in the early hours of the morning, making the old cliché 'carriages at midnight' completely false. For instance at the Duchess of Bedford’s Ball at Bedford House in London on Friday 31st May 1811, at which the great Neil Gow provided the music, the supper was served in the wee hours,'At half-past three o’clock the company sat down to a sumptuous banquet, the viands and wines being of the first description, with a desert of ices, strawberries, cherries, and grapes by Mr Gunter. Music was provided by Mr Gow’s Band'.

The Morning Post of 14th April 1813, the year of our recreated ball, reported a very grand supper served at a magnificent ball in the home of a Mrs Beaumont,

'At 2 am the company then adjourned to the supper-tables. Here a most sumptuous display indeed was made, there were no less than six supper-rooms, all fitted-up in the most beautiful and appropriate manner. Each table was brilliantly ornamented with trophies of war and peace; emblems emblematic of the arts and sciences: the costume of all civilized nations of the earth, exemplified in waxen images, modelled for this fete expressly…the plate, and the china, displayed and the brilliancy of the lighting-up of the tables, the effect was grand in the extreme. To render the coup l’oeil complete, about two hundred beautiful women (for the major part of the females were really beautiful) sat in such prominent situations as to be seen in every part without the least difficulty. The supper, we need not add, was most excellent; the wines abundant, and all of the rarest kinds. The dessert fruits, and confectionary, were equally deserving of panegyric: the Duke of Clarence spoke in raptures of them'.

Amazingly, when my team did finally recreate the supper for filming at Chawton House in January, because the schedule was running very late, the food was not delivered to the table until 2 am. And we finished the washing up at 4.00 am. That day we started work in the kitchen at 7.00 am, making it a massive twenty-three hour shift! This sort of schedule was probably exactly the long kind of day that the servants who prepared and served at these affairs would have actually experienced.

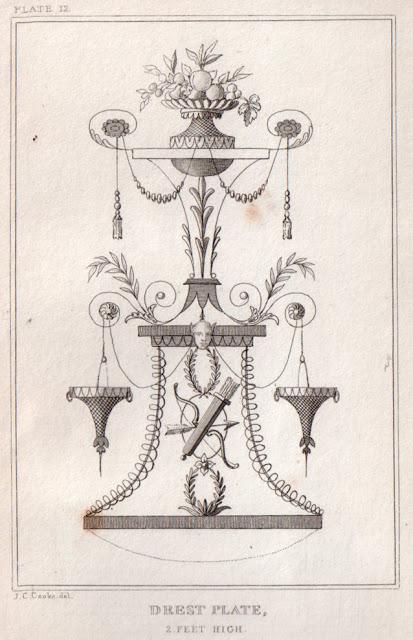

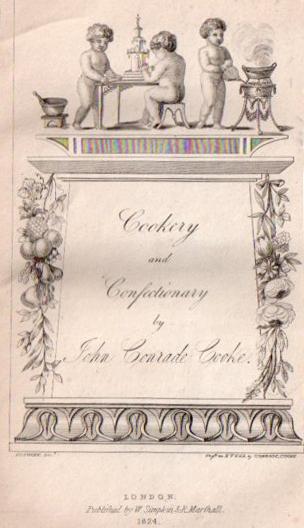

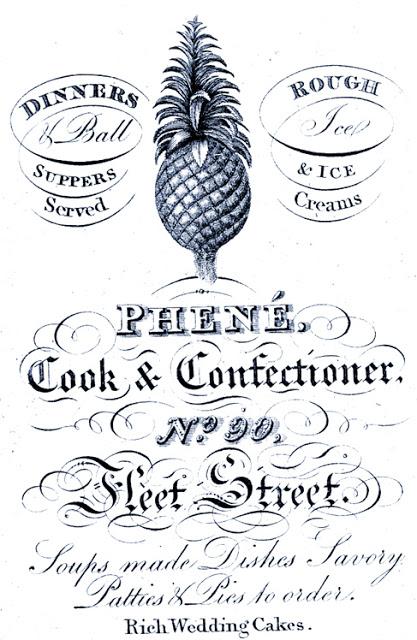

In the description above of Mrs Beaumont's ball, it is mentioned that the tables were decorated with emblematic wax ornaments. These pieces montées, or 'dressed plates' were also made out of sugar and edible materials. They were designed and made by very skillful confectioners who specialised in such work, and could even be hired just for the evening. One little known, but important book by the cook and confectioner John Conrade Cooke - Cookery and Confectionery (London: 1824) illustrates some of these extraordinary objects. The example I reproduce below was a sort of culinary 'mobile' that trembled elegantly when the guests sat at the table. It was appropriately called a 'tremblent'. These stunning wobbly centrepieces were popular all over Europe until the middle of the nineteenth century.

A 'drest plate' or tremblent by John Conrade Cooke. Although there was neither time, nor the budget to make table ornaments like this for the programme, I did make two of Cooke's ices for our reconstruction of the Netherfield ball supper - tamarind ice cream and negus ice, both served during the dessert in contemporary ice coolers, or seaux à glace.

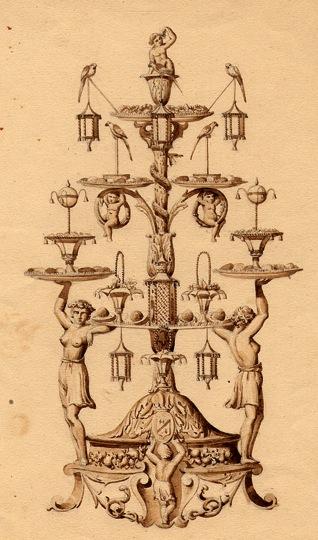

A remarkable design for a tremblent by the Turin confectioner Prati c.1825

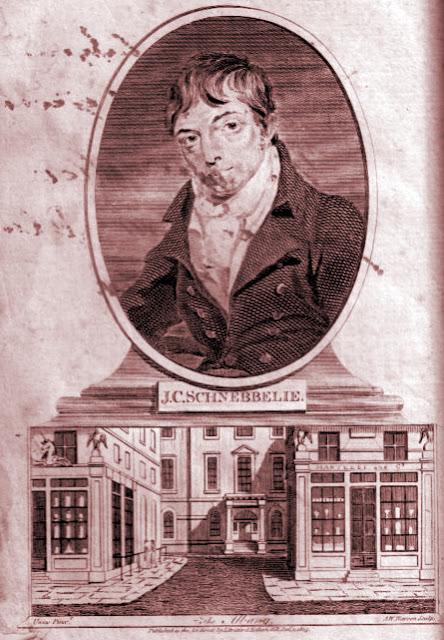

Bills of fare for ball suppers are actually few and far between in the cookery literature of the period. One of the best examples and the one we decided to use as the starting point for our supper was published in later editions of William Henderson's The Housekeeper's Instructor. It first appeared in the 1805 edition, a version of the book much 'corrected, revised and augmented' by Jacob Schnebbelie, principal cook at that iconic residence for high status bachelors - Albany in Piccadilly.

| Portrait of Schnebbelie with the Albany from William Henderson, The Housekeeper's Instructor (Twelfth Edition, London: 1803). |

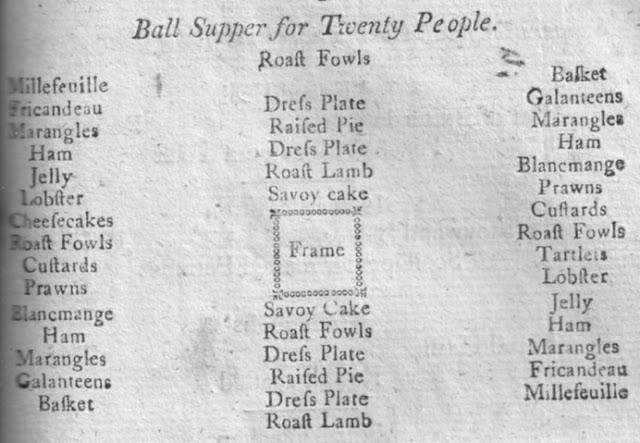

It is likely that Schnebbelie fed such regency worthies as Henry Holland, Lord Byron and Robert Smirke, who all lived in chambers or 'sets' in the Albany on his watch. Schnebbelie's scheme includes four dress plates down the middle of the table with a small dessert frame in the center. These raised frames, also called plateaux or surtout were very popular for raising dramatic ornamental centrepieces above the level of the table. With four dress plates and a frame, this layout is for a very ambitious entertainment indeed - to my mind, in style and scope somewhat more Mr Darcy than Mr Bingley. On either side of the frame is a Savoy cake. These large moulded sponge cakes were decorated with gum paste ornaments and made conspicuous ornaments for the table in their own right. I decided to drop the dress plates. but retain the savoy cakes.

Schnebbelie's ball supper scheme, with its 'frame' and 'dress plates' is for a very grand ball supper. He also included a plan for the dessert which followed. From William Henderson, The Housekeeper's Instructor (Twelfth Edition, London: 1803).

This large gum oaste triumphal arch with its trophies stands on a dessert frame or plateau. I made it for the exhibition Royal Sugar Sculpture in 2003. It is now displayed in the table decker's room at Brighton Pavilion

In this decorative title page to Cooke's book, the two little fellows at the table are preparing a 'drest plate'.

One of my ornamented Savoy cakes. Photo by Andrew Hayes Watkins. © Optomen Television

A Regency period mold in my collection, which I used to ornament the Savoy cake above.

Ball suppers were prepared and served by professional caterers with advanced skills in both cookery and confectionery. Photo by Sarah Durdin Robertson.

Schnebbelie includes two blancmanges in his scheme, which were likely to have been made in the intricate moulds of the period.

Schnebbelie's cold fowls were likely to have been ornamented with fashionable silver hatelet skewers garnished with such delicacies as whole truffles and crayfish. Photo by Andrew Hayes Watkins. © Optomen Television.

Instead of a dessert frame, we used a stunning epergne by Benjamin Smith III of Birmingham, kindly lent by Koopman Rare Art. Photo by Andrew Hayes Watkins. © Optomen Television

Photo by Andrew Hayes Watkins ©Optomen Television

Many of the savoury dishes in the meal were from Henderson's book, though some, such as the Austen favourites white soup and haricot of mutton were based on recipes in Martha Lloyd's and the Knight family manuscripts.

Crayfish in Jelly. Photo by Andrew Hayes Watkins. © Optomen Television.

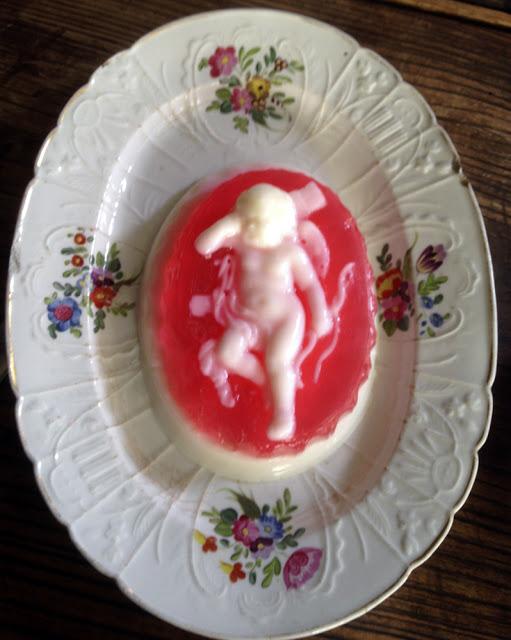

A sweet jelly this time, moulded in cameo style made using a 1790s Staffordshire mold.

If you live in Britain and you missed the programme, you can catch up with it over the next week on BBC iPlayer.Watch Ivan make Frederick Nutt's 1789 Spice Biscuits