Alan Bean in 1971

Alan Bean in 1971I do not remember my high school years with fondness. My parents didn’t let on at the time, but they worried about me. Apart from playing the guitar, I was disengaged.

Subjects like English and Social Studies came easily to me and I excelled without much effort. But I was a terrible math student and struggled with subjects like chemistry and physics that involved numbers. Moreover, I resisted all offers of assistance.

Church and Sunday school attendance were mandatory in the Bean family; staying home never crossed my mind. But hymns seemed horribly old fashioned and I had a saying of which I was inordinately proud: “I never liked a sermon so much that I wasn’t happy when it was over.”

McLaurin Memorial Baptist Church “celebrated” communion on a monthly basis. It was an exceptionally dreary affair, as I recall, but I don’t recall much because, being unbaptized and technically unregenerate, I wasn’t allowed to participate. During the closing hymn the heathen were required to slink out of the sanctuary, waiting in the foyer until the true believers had completed their pious ritual.

I hardly remember anything about Sunday school. The lessons were moralistic, students kept the interesting details of their lives under wraps, and I learned amazingly little about the Bible. In my senior year of high school I read the good book clear through from Genesis to Revelation as a kind of pious exercise. I wondered why most of what I was reading never came up in sermons or Bible study and concluded that we were being given a guided tour through the book that avoided the bits that didn’t comport with evangelical orthodoxy.

I now realize that, for most Baptists at the time, the Bible was more a source of consternation than inspiration.

McLaurin belonged to the Baptist Union of Western Canada, a moderately evangelical denomination. A few Baptist Union churches were hardcore fundamentalist and a handful (like First Baptist, Edmonton) were reputed to be liberal (whatever that might mean), but most were dedicated to avoiding theological disagreements at all costs.

This requires a little historical background.

Canadian Baptists decided not to participate when the Methodists, Presbyterians and Congregationalists formed the United Church of Canada in 1925, but we were in on the early negotiations. In 1937, the Baptists agreed to share a hymn book with the United Church of Canada (a thick but tiny volume called The Hymnary) and also shared Sunday school curriculum. We once thought of ourselves as a “bridge denomination” between liberal denominations like the United Church and the Anglicans and conservative groups such as the North American (German) Baptists, the Pentecostals and the Christian and Missionary Alliance.

The bridge began a slow collapse in 1960 when the United Church introduced a new Sunday school curriculum designed to minimize the divide between the seminary classroom and the pew. Overnight, the book of Jonah became a pious fable and the virgin birth was ruled a myth. Liberal United churches in the big cities were happy with the “new curriculum” but the revolt in more conservative rural and small town churches created a well-publicized scandal.

For Canadian Baptists, the new curriculum was a non-starter. By 1965, we had withdrawn from our cooperative relationship with the United Church and, shortly thereafter, we produced our own hymn book. By 1980, the Baptist Union of Western Canada had withdrawn from the Canadian Council of Churches.

As a high school student in the late 1960s, I was completely unaware of these developments, but it helps me understand the rather chilly religious atmosphere I encountered. Free to select Sunday school materials that appealed to them, churches like McLaurin started ordering conservative evangelical products from American publishing houses like David C. Cook and Gospel Light.

The lessons created for adolescents tried to sound hip, but they were invariably moralistic, preachy and unspeakably boring.

As an adolescent, I lived in two irreconcilable worlds: the conservative, conventional, upright world I encountered on Sunday mornings, and the revolutionary soundtrack of the mid-to-late 1960s. Some of the greatest popular music ever recorded came out of this period: The Beatles, the Stones, the Who, Simon and Garfunkel, James Taylor, Leonard Cohen, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and all the rest.

I tolerated the churchy world of Sunday morning, but I had sold my soul to rock and roll. When I outgrew my father’s baritone ukelele, I bought my first guitar at 15 and signed up for lessons at Lillo’s School of Modern Music.

Noticing my new-found interest in music, I was asked to “share a special” on Sunday morning. I selected a lovely tune by Peter, Paul and Mary called Hymn, a highly nuanced song about a clueless young man who recoils from the God-is-dead theology then popular in ultra-liberal circles.

Passing conversations where they mentioned your existence

And the fact that You had been replaced by your assistants.

The discussion was theology,

And when they smiled and turned to me

All that I could say was “I believe in you.”

I knew nothing of the death of God movement, of course, but, like the guy in the song, I was a believer in spite of my theological ignorance and confusion.

When I finished tuning my guitar I realized that, consumed by stage fright, I had completely forgotten the melody. I did recall the lyrics and the chords, however, so I plunged ahead anyway, singing the first verse in a weird monotone. After a very long instrumental break, the melody came back to me and I got through the rest of it without incident. I particularly liked the closing verse, but I’m sure it confused my audience:

My mother used to dress me up,

and while my dad was sleeping

we would walk down to your house

without speaking.

I wasn’t much of a guitarist at first, but when you spend two or three hours a day at anything you advance quickly. On weekends I would get together with a few of my friends to play and sing Gordon Lightfoot and Simon and Garfunkel songs. Since my home was a block from Strathcona High School, we would eat our brown bag lunches while listening to Bridge Over Troubled Waters or Abbey Road. I made a song book of my favorite songs and try to figure out the right chords. All the songs I liked back then have held up marvelously.

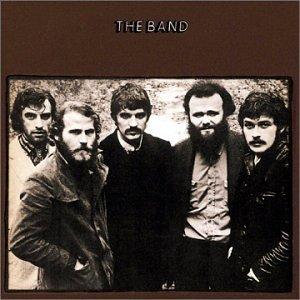

I remember my father being concerned about Paul Simon hanging with “the whores on seventh avenue.” He called “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” was “a morbid little opus” and once perused the album cover of “The Band” with obvious distaste. “I wouldn’t want to meet those guys in a dark alley,” he said.

I remember my father being concerned about Paul Simon hanging with “the whores on seventh avenue.” He called “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” was “a morbid little opus” and once perused the album cover of “The Band” with obvious distaste. “I wouldn’t want to meet those guys in a dark alley,” he said.

But generally my parent’s didn’t comment on my taste in music. They just wished I would study harder and take more interest in religion . . . or girls, for that matter.

I was taking an interest in girls; I was just too insecure to do anything about it.

There are two kinds of people in this world: those who remember their high school years fondly, and those who merely survived them. If you are (or were) athletic, tall, extroverted, exceptionally attractive, or some blessed combination of these qualities, plenty of scenes from high school are probably on your sentimental highlight real. For the rest of us, Janis Ian said it well:

And those of us with ravaged faces

Lacking in the social graces

Desperately remained at home

Inventing lovers on the phone

Who called to say “come dance with me”

And murmured vague obscenities

It isn’t all it seems at seventeen.

Perhaps you remember the cool kids dancing in the gym while the rest looked on, wondering what it would be like to be the kind of girl who is asked to dance or the kind of boy with the confidence to do the asking.

I was a reasonably good athlete, but I wasn’t big enough, tall enough, strong enough, or fast enough to play at the varsity level. I went to a largish high school where only the real jocks made the team. The rest of us would play sandlot football in the summer and, when the snow came, we would shovel the local rink at 7:00 in the morning, then stand at the blue lines and sing “O Canada” before playing pickup hockey (that bit I do remember fondly).

I think I was the only kid from my high school at McLaurin Baptist, so church represented an entirely different social world. I was closer to the kids in the church youth group than to my school friends. We would get together on Friday nights and drive around aimlessly. We once drove three hours to Calgary because the first McDonald’s in Alberta had just opened there. It was a dumb idea and I knew it, but we had a good time anyway.

In my senior year no one volunteered to lead the youth group so we were on our own. Most of us had grown up Baptist, so we decided to attend different kinds of churches in the evening (everybody had evening services back then). We checked out Central Pentecostal hoping to see some crazy goings-on, but were very disappointed. Pentecostal churches tend to tone it down when the members attain middle class status as they had at Central.

We attended an independent gospel church where a young man paced the stage, wiping away the sweat with a white towel while reminding us over and over that the Devil was like a roaring lion seeking whom he may devour. He had little else to say, but on that one point he was adamant about the Devil being a lion.

One night we showed up at Beulah Alliance where the pastor had large cardboard cutouts of the various beasts from Revelation. Years later, I was told that the pastor once concealed a cardboard cutout of the Antichrist behind a curtain which he dramatically whisked away while shouting, “and then shall the son of perdition be revealed!” The diminutive choir director, who had not been informed in advance of the pastor’s stunt, was behind the curtain organizing sheet music and couldn’t understand why everyone was laughing so hard. Apparently the hilarity swelled to the point that the rest of the service was cancelled.

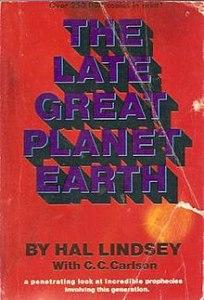

I never heard much about Bible prophesy growing up, but that began to change in my high school years. Hal Lindsey published his first book, The Late, Great Planet Earth in 1970 when I was in the eleventh grade (or grade 11 as we called it in Canada). A graduate of Dallas Theological Seminary, Lindsey gravitated to California where he worked for Youth for Christ until 1969. The Late, Great Planet Earth became the bestselling book of the 1970s because it was written with young people in mind. Lindsey knew his audience. We were fearful, confused, suspicious of organized religion and other manifestations of “the establishment” and we eager for the next thrill.

The Late, Great Planet Earth was designed to scare the hell out of its target audience. Everyone at church was reading the book and my parents had a copy, so I gave it a go. Unfortunately, I made the mistake of reading Lindsey with a Bible beside me so I could look up his biblical references. I couldn’t see much connection between Lindsey’s claim that we were living in the last days and the passages he cited.

The Late, Great Planet Earth was designed to scare the hell out of its target audience. Everyone at church was reading the book and my parents had a copy, so I gave it a go. Unfortunately, I made the mistake of reading Lindsey with a Bible beside me so I could look up his biblical references. I couldn’t see much connection between Lindsey’s claim that we were living in the last days and the passages he cited.

I pronounced the book a piece of crap and moved on.

Looking back, I am a bit surprised by the depth of my youthful skepticism. I suspect I was put off by the author’s thinly disguised political conservatism. The Bean family bought our first television in 1964, the year we arrived in Edmonton, just in time to witness the concluding chapter of the civil rights movement. For me, that was real religion.

I think the influence of Tommy Douglas also had something to do with my skeptical reaction to Lindsey’s conservatism. Douglas introduced universal health insurance as premier of Saskatchewan and, by the time I entered high school, the idea had been embraced at the national level.

This played out against the backdrop of the Vietnam war which was opposed by almost everybody I knew. Young Canadians like me expressed our patriotism by opposing American foreign policy, in general, and Richard Nixon, in particular.

I wasn’t politically engaged at all, but I had unconsciously imbibed a progressive, anti-war, pro-civil rights outlook and Lindsey’s dismissive references to “socialism” and the United Nations put me off.

Also, by this time, I had started dabbling a little in C.S. Lewis, the Oxford professor. Lewis was theologically and politically conservative, but his theology was traditional Church of England orthodoxy, he appealed to reason, showed flashes of brilliant insight, and his prose was brilliant in its simplicity. Compared to Lewis (the only other theologian in my limited experience) Lindsey didn’t cut it.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, I was beginning to swap ideas with Richard Sherbaniuk, a high school acquaintance who was reading a lot of Bertrand Russell and making casual references to influential thinkers I had never heard of. Like me, Richard was a so-so student who rarely did his homework, but he was the only person I knew who read thick books for pleasure. This set him apart from most of our high school teachers. School bored Richard, but ideas excited him. His saving grace, from the school’s perspective, was an innate ability to run really fast. Richard had also grown up with the cool kids so they didn’t intimidate him. I guess he talked to me because, unlike most people, I was genuinely interested in what he had to say.

At my fortieth high school reunion I was shocked to learn that my classmates regarded me as something of a Bible-thumper. Maybe it was because, on those rare occasions that the subject of religion came up, I would do my sworn duty as a defender of the faith. Our Sunday school lessons taught us how to do that, but the skill was rarely needed.

My holy Joe reputation was likely a function of what I didn’t do. I didn’t date, I didn’t drink until I was 18, and I didn’t go to parties. The idea of getting drunk never appealed to me and no one ever invited me to their parties, possibly because they feared that, while everyone else got falling-down-drunk, I would remain sober and hold them in contempt. On Monday mornings, the kids in my home room would talk about how much they drank over the weekend, how violently they threw up, and what great fun it all was. I didn’t like being left out of the action, but I have never enjoyed throwing up.

My social awkwardness was exacerbated by lack of practice. A cute girl from church once asked me to accompany her on a group date. I had no idea how to act. None. She had to tell me to walk her to the door. I’m not sure which of us was the most embarrassed.

When no one volunteered to lead the youth group, we made do on our own. We once held a retreat in the middle of a farmer’s field, (I assume someone got permission from the farmer), and made an attempt at Bible study. We were pooling our ignorance, but we had a lot of ignorance to work with. Years of Sunday school had taught us surprisingly little about the Bible. But, again, we had a lot of fun.

Two of my male church friends once told me that they had recently “talked to Jesus” while smoking grass. Apparently, that worked out great. I couldn’t have been less interested. Sometimes my skeptical streak has served me well.

Generally, my church friends had a bit more social capital than I possessed. They drove cars (I didn’t get my license until I was 18 and was married before I purchased my first car). Many of them were athletes, which opens up all kinds of social opportunities. They dated. They got drunk and smoked a little dope. But when they got together as the church youth group I was always invited.

During m high school years, my parents were part of the charismatic renewal movement that was sweeping the continent. Since there was no youth group, my mother’s hair dresser invited us to some gatherings in her home and one experience remains lodged in memory. Most of the kids in the room were strangers as was the middle aged man telling us that when real Christians gather to praise the Lord they should expect to speak in tongues and receive visions from the Lord. And whether you get “a tongue or a vision”, he emphasized, someone in the room will always be given the interpretation.

As if on cue, one of the kids interrupted to report a vision. The Lord had shown him a bundle of sticks bound together with a rope. “Simple,” the speaker shot back. “One lone stick can be easily snapped, but when we are bound together by the love of Jesus can overcome the Evil One.”

He tried to go on with his lesson, but the young man kept interrupting him with one new vision after another and as the details kept getting weirder the interpretations became more strained. “I was looking at the fireplace,” the kid reported. “And, as I looked, the fireplace got bigger and bigger until it filled the entire room.”

“Sometimes,” the speaker said testily, “we must distinguish between a vision from the Lord and an over-active imagination.”

I was relieved to learn that there were limits to the madness.

I also remember the day one of my church friends handed me a Chick Tract, a little comic book about an impressionable adolescent male who comes under the influence of a hip swinger with a fancy car. The groovy guy introduces the neophyte to pot, alcohol and illicit sex. All is well until a car crash sends the both swinger and his disciple to the afterlife. The kid is horrified when his hop buddy rips off his mask to reveal his true identity: Satan himself.

“Isn’t that just the coolest thing ever?” my friend asked me. I was speechless. My friend was tall and good looking who struck me as a bit of a groovy guy himself. Why was he attracted to this garbage?

For the first fifteen years of my life I was exposed to a very bland, nondescript, but entirely respectable brand of religion. Now, with the end-of-the-world speculation, the tongues-speaking, the visions from the Lord, and a sudden fascination with the demonic, my religious world was getting weirder by the day.