According to the National Registry of Exonerations, there have 2,551 known exonerations in the United States since 1989. An additional 1,800 defendants have been cleared in 15 large-scale police scandals in which police officers framed innocent defendants. But experts agree that these figures represent the tip of a much larger iceberg. For every innocent person that walks free, a dozen more languish behind bars.

David Black is one of them.

The leading cause of exoneration, involving 72% of wrongful conviction cases, is mistaken eyewitness identification. But when eyewitnesses make mistakes, it is typically because, often unbeknownst to juries, investigators have been manipulating the identification process in subtle, and not-so-subtle ways. This is called police-generated testimony. And if you want to understand how police-generated testimony works, the tragedy of David Black is exhibit A.

I am not suggesting that most of the people locked up in America are innocent. Most crimes involve little guess work. Evidence of guilt is typically so overwhelming that only three percent of state cases, and two percent of federal cases, make it to trial. Most are settled by plea bargain.

And of the cases that do go to trial, few end well for the defendant. In the federal system, only 2% of defendants are acquitted. These odds are so daunting that some innocent people take a plea offer because they don’t like their chances at trial. Still, the vast majority of criminal defendants are guilty as charged and everybody knows it.

But what about the small percentage of cases where the facts are in dispute? What happens when the prosecution and the defense can argue the facts with equal facility? In theory, cases like that should never go to trial. Guilt must, after all, be proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

In reality, it isn’t so simply. Especially when we consider tragic crimes of violence involving innocent victims. What happens when the evidence is muddled and a jury must decide between convicting an innocent and putting a dangerous killer back on the street? They will vote to convict. Almost every time.

The two witnesses that sent David Black to prison were ridiculously, even grotesquely unreliable. If they were in a movie, their performance, in and out of court, would make for high comedy. But there is nothing funny about an innocent man spending twenty-five years in prison.

The “evidence” used to convict Mr. Black was placed in the mouths of uncooperative witnesses, but it was generated by the police in every detail.

An act of violence that horrified a community

David Black stood accused of firing a 9mm handgun at James “June Bug” Smith at the conclusion of a loud, lengthy and dramatic argument on the 400 block of K Street in Washington D. C.

The government alleged that, as June Bug fled in a southeasterly direction down K Street, Black walked to his blue Toyota, fished a handgun out of the glove compartment, rested his hands on the roof of the car, and fired two shots. Black didn’t hit June Bug, so the government’s story goes. A stray bullet missed its intended target and passed through the heart of a diminutive, elderly Chinese-American woman named Alice Chow.

The senseless killing of Alice Chow horrified the community. She had grown up in and around Washington’s Chinatown. Fluent in both Mandarin and Cantonese, she volunteered as an interpreter for Chinese immigrants who spoke little English. She lived a simple, dignified and consequential life, scraping by on Social Security checks and subsidized rent. Her world was within walking distance of her home. Every Sunday morning, she walked to the Saint Mary Mother of God Catholic Church. And every day, come rain or come shine, she walked to the Chinese Community Center housed in the socially conscious Calvary Baptist Church on 8th Street.

Both locations were less than half a mile from her apartment in the Museum Square One apartment building on the corner of K and 4th streets where Ms. Chow served as vice president of the residents’ association. The community was horrified by the senseless slaughter of a model citizen. The pressure on police investigators to find the killer was immense.

Six impossible things before breakfast

There is an Alice in Wonderland quality to the David Black story. Lewis Carroll dragged his young heroine through an upside-down universe where a series of pompous adults spout nonsense with supreme confidence. In Alice Through the Looking Glass, the White Queen asks Alice for her age.

“I’m seven and a half exactly,” Alice replies proudly.

`You needn’t say “exactually,”‘ the White Queen replies: `I can believe it witho

ut that. Now I’ll give YOU something to believe. I’m just one hundred and one, five months and a day.”

When Alice says “I can’t believe THAT!” the Queen feels sorry for her.

“Can’t you?” the Queen says. “Try again: draw a long breath, and shut your eyes.”

“There’s no use trying,” Alice protests with a little laugh, “one CAN’T believe impossible things.”

“I daresay you haven’t had much practice,’ the Queen replies. “When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.” When you take a careful look at the details of the official story presented at David Black’s trial, it crumbles to dust. It’s impossible.

Impossible Thing one: The witnesses were too far from the action to make an accurate identification

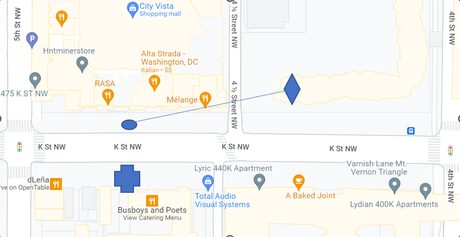

According to a number of scientific studies, when more than 150 feet separate one person from another, visual recognition drops to zero. Larry Johnson and Barbara Marshall were approximately 250 feet from the scene they described. Both witnesses claimed they knew David Black (the alleged shooter) and June Bug (the intended target) by sight. But that only helps if Larry and Barbara were close enough to distinguish facial features. They were not.

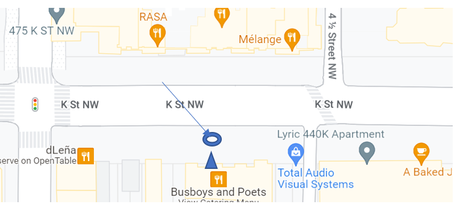

In the picture above, a man is holding a large sign, several times the size of his face. On the left we see a close-up; on the right, we see the view from 250 feet. Not only can you not see the man’s face; you can’t read the sign. Again, this is the distance between the witnesses in the David Black trial and the action they witnessed. At trial, Barbara Marshall said she knew the men were fighting because she could see the anger on their faces. That was impossible. (Note: The buildings that appear to be in the way weren’t there in 1997.)

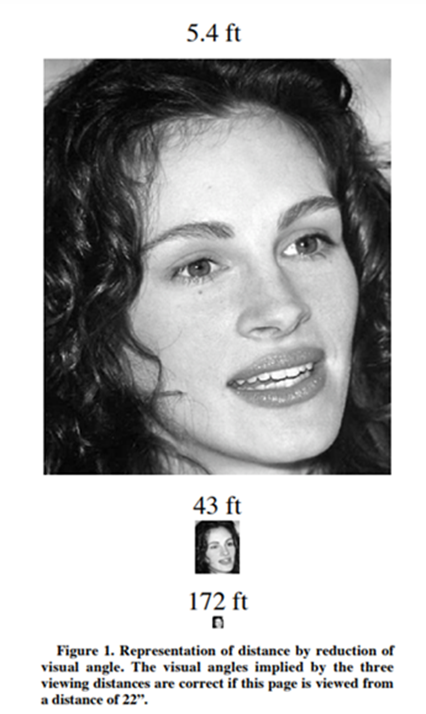

In a 2009 study, test subjects were shown a large picture of celebrity actress Julia Roberts. The test started at a considerable distance and moved progressively closer. At 5.4 feet, everyone identified Julia Roberts (the lips are a dead giveaway). At 43 feet, some did, some didn’t. At 172 feet, the image was far too small for test participants to even guess at an identification.

At trial, Barbara Marshall admitted that her vision is extremely poor and claimed she wasn’t wearing her glasses on the day Alice Chow died. But even if she and Larry Johnson had enjoyed 20/20 vision, they were simply too far from the scene to identify David Black, or anyone else.

Impossible Thing Two: Witnesses stationed thirty feet from the action saw and heard nothing

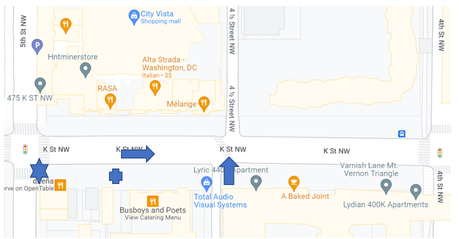

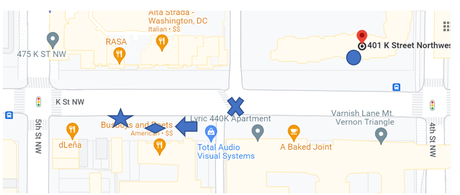

According to trial testimony, the government’s star witnesses saw David Black and June Bug arguing on the street across the street from Lily Memorial Baptist Church. They were waving their arms and screaming at one another. The “ruckus” was so loud, in fact, that Larry moved to the window to see what was going on. Suddenly, while the two men were standing at the front of a blue Toyota, June Bug raced across K street, angling toward “the alley” (41/2 Street on the map below).

While all this drama was going down, three women were chatting on the opposite side of K street, less than thirty feet away. They heard nothing. They saw nothing. A fleeing June Bug, according to the official narrative, would have passed within ten feet of the women. They didn’t see him.

In the official story, Black fired a 9mm handgun less than thirty feet from the women. They heard a popping sound which, initially, they didn’t recognize as gunfire, but they didn’t see the blue Toyota or a man discharging a weapon. The discharge from a handgun at close range is deafening. That’s why people lose their hearing if they don’t wear ear protectors at the firing range.

It would have been impossible to carry on a polite curb-side conversation with two men screaming at one another immediately across the street. A running man passing within ten feet of the women would have been impossible to miss.

Seconds after Alice Chow collapsed on the sidewalk, Larry Haskell, a resident of 401 K Street, emerged from the alley (41/2 Street NW) and ran in the direction indicated by the arrow to the right. All three women (represented by the cross in the map above) witnessed this sudden burst of action. An assistant pastor who was walking toward 5th Street with a parishioner (see the star above) thought the running man might be the shooter and gave chase.

Yet none of these street witnesses saw or heard the argument, the flight of June Bug, the shooter, or the blue Toyota. There is a simple explanation: they weren’t there.

Impossible Thing three: A bullet intended for June Bug could not have struck Alice Chow

By the time the Washington Post described the shooting the day after the incident, the stray-bullet theory was already viewed as established fact. After all, why would anyone want to shoot an elderly human rights activist on a quiet street? The police never entertained an alternative theory.

But the government’s insistence that Ms. Chow caught a bullet intended for a fleeing June Bug can’t bear up under scrutiny.

At trial, the government’s star witnesses, (sometimes with considerable coaxing) told the same story. First, June Bug ran in a southeasterly direction down K street toward “the alley” (see the arrow in the diagram above). At the same time, Black moved from the front of the car to the passenger side, opened the door, procured a gun, exited the vehicle, placed his arms on the top of the car, and fired two shots.

How long would it take a man, however quick and efficient his movements, to perform that operation. At least five seconds (more, if he had to fumble in a glove compartment or under a seat).

The average person can run seven meters in one second, which translates to thirty-five meters (114 feet) in five seconds.

You see the problem. For a stray bullet to strike Alice Chow (represented by the crossed oval above) June Bug couldn’t have progressed more than ten feet before shots were fired. Had he run 114 feet, he would have been almost to the crosswalk (marked by the cross). Given a five-second head start, a running June Bug would have been so far east on K street that even the wildest shot would have missed Alice Chow.

Impossible Thing four: A bullet fired from the south side of K street would have struck the victim on the right side.

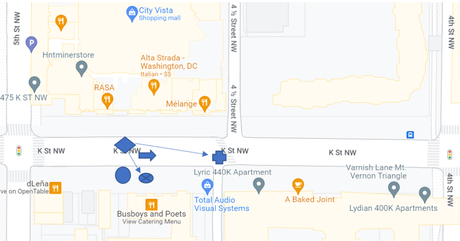

According to the autopsy presented at trial, the bullet that killed Alice Chow entered her left armpit, passed through her heart, and exited her right armpit. The trajectory was slightly upward. Ms. Chow’s left side faced the buildings on the south side of K Street; her right side faced the street. The map below contrasts the actual trajectory of the bullet (fat arrow) with the trajectory a bullet fired from the north side of K Street (skinny arrow).

If the jury had understood this problem, a guilty verdict would have been off the table. They didn’t.

Impossible Thing five: The prosecutor told the jury that Ms. Chow was about to cross K Street.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Ken Whitted realized that the bullet that killed Ms. Chow was fired from her left. He also understood that a bullet fired at a fleeing June Bug couldn’t have struck her at all. He had a solution.

Every made-for-television courtroom drama concludes with closing arguments. It is rarely mentioned that the prosecutor is allowed to close twice, first and last.

Savvy prosecutors reserve their weakest arguments for the second close because the defense can no longer respond.

Since everyone knows that Alice Chow was walking home from church, Whitted reasoned, and since all the evidence suggests she was walking west on K street, she must have been in the process of turning at the crosswalk when the bullet struck her. This explains, he argued, why her left side was exposed.

That’s impossible. Street witnesses were unanimous that Ms. Chow fell just thirty feet shy of Lilly Memorial Church, or 150 feet past the crosswalk (41/2 Street) when the bullet struck her. Whitted’s reconstruction of the crime scene was irresponsible, impossible, against all the evidence, and successful.

Four different street witnesses saw a man dressed in military fatigues run across K Street a second or two after Alice Chow fell. He crossed at the crosswalk, dodging traffic as he went. The man they saw, Darrell Haskell, corroborates this testimony. If Ms. Chow had crossed at the crosswalk, Haskell would have tripped over her. As it was, he didn’t see her at all. That’s because she was lying 150 feet to the west.

Impossible Thing six: Alice Chow could not have been walking home from church when she died.

The jury fell for the prosecutor’s sleight-of-hand because a simple fact had been repeated dozens of times during the trial: Alice Chow was walking home from church when she died. Whitted belabored the point in his opening and in both his closing statements. His questions reflected this commonly-held belief. Whenever the Chow murder was covered by the Washington Post the fact that she had been returning from church on that fateful day was stated as fact.

But it wasn’t true. We don’t know for sure where Alice Chow was headed shortly before 2 pm on February 2nd of 1997, but it wasn’t home from church.

It is virtually certain that Ms. Chow had attended church the morning she died. The Saint Mary parish church lies in the heart of Washington’s historic Chinatown. The Rev. Victor Wong, a personal friend of Ms. Chow, celebrated a Chinese mass every Sunday morning at 11:30. Mass lasted just under an hour, and (thanks to Google) we know the walk home would have taken approximately ten minutes.

In other words, she had time to walk home, have lunch, change clothes, ride the elevator down to the street, and head west on the south side of K street in the direction of 5th Street (which is where all the street witnesses placed her). Likely, she was heading for the Chinese Community Center which she attended on a daily basis.

The wrong spot, and the wrong direction

In this map, the star represents Lily Memorial Baptist Church, the circle indicates the Museum Square One apartment building where Alice Chow resided, the star is the spot on the sidewalk where three women were chatting after worship, the arrow marks the direction Ms. Chow was walking, and the diamond indicates where she fell.

If Alice Chow was walking home from church, she would have been walking in the opposite direction. There are two routes from Saint Mary Parish Church to the apartment building where she lived. She could come home via 5th Street or 4th Street. Either way, she would have crossed K street at the walk light. An elderly woman would have avoided the crosswalk altogether. And, more significantly, she would have been walking east, not west. There is no route from the church to her home that would have placed her where she was when the bullet ended her life. The entire construction is impossible.

A simple alternative

Remove David Black, June Bug and the blue Toyota from the picture and all six impossible things disappear. But if investigators had been satisfied with reliable witness testimony they wouldn’t have been able to please the public by closing the case. There would have been no shooter, no gun, no blue Toyota. Just the sound of gunfire, a dead woman on the street, and no idea what had happened.

The police needed a killer. So, they found one. That’s the story for next time.

- Police-generated testimony 1: Six Impossible things before breakfast

- Police-generated testimony 1: David Black is innocent (and I can prove it)

- A day of reckoning in Winona, Mississippi: Why Fannie Lou Hamer and Curtis Flowers are forever united in a corner of my mind

- Returning to the scene of the crime

- The Science of False Confessions

Email Address: