Not so long ago, I found myself in an unexpectedly warm discussion with someone about the fate of printed poetry magazines. It was partly my fault and he was quite right to point out that their waning fortunes were, largely, down to rising postage costs. I don't think that tells the whole story, though. I said to him that it was also, perhaps, down to the rise of online poetry magazines, which he disputed, claiming no-one actually read them. This got me thinking. It's an uncomfortable question, but how many people who've bought printed poetry magazines over the years – even in their heyday – actually read them from cover to cover? I suspect a lot of buyers are poets wanting to to check out a magazine prior to submission or who feel they should support a particular magazine. It would be naive to think subscribers and readers are the same thing. And even if all the subscribers to a particular magazine were avid readers, if you get a poem published in it, then like all poetry in printed books and magazines, it's going to sit there in the dark for all but a couple of minutes of a reader's life (less, if it doesn't engage them), pressed up against a similarly unread poem on the opposite page.About six months ago, I bought a box of tall glasses. I take a new glass from it from time to time if I break one or need an extra one. They're all individually wrapped with bubble-wrap and sellotape. I unwrapped one the other day to discover it had two dead spiders in it. They must've been there since the glasses were wrapped and packed. While still alive, they'd filled the glass with a fog of spider-web. Imagine my surprise when, as I tried to clean it out, one of the 'dead' spiders came to life, scuttled across the work-top and disappeared behind a row of storage jars. Rather like a poem in a magazine, it had sat in the dark for heaven knows how long, before suddenly bursting into my world for a few moments – only to disappear back into the darkness. If it were a poem, it would be a good poem, as I'm unlikely to forget it and here I am writing about it and talking about it to anyone who'll listen. As is often the case, I think we often make too much of the difference between work found on the internet and its analog counterpart. In both cases, what we write has one chance to grab the attention of the reader. If it fails, it suffers the fate of the unfortunate second spider. What matters is not whether it's published in an online or in a print magazine: what matters is whether it's a good poem or not.With a print magazine, the fact that you can hold it in your hand means it speaks to you before you actually read it. The medium is the message almost as much as the poetry it contains. That it had to be designed, typed, photocopied, folded, stapled and distributed, all from the much-vaunted kitchen table, adds to its aura. And you might want to make your poetry into a beautiful, physical thing – as, say, Blake did – and I'd have no argument with you: it's great that people still do this. It's great, too, that some online magazines issue occasional hard-copy anthologies. Nevertheless, it's impossible not to notice that poetry lends itself to the internet: there's no getting away from the fact that most poetry fits very nicely on a screen. And there's no escaping the fact that internet pages – though less permanent than print – can have an aura of their own. It springs not only from the craft involved in making them (which any writer of HTML in the early days of the internet can attest to), but the fact that you never really know where it is: you can't take hold of it and, like Frankenstein's reconstructed man, it takes electricity to bring it alive.

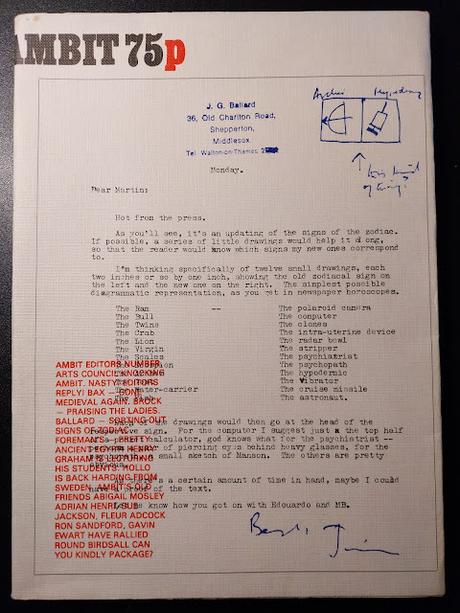

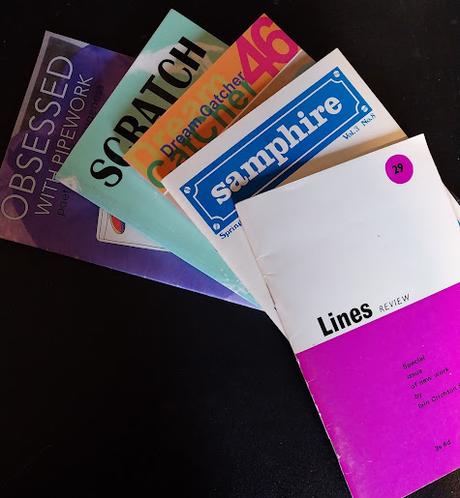

When you get a print magazine in your hand and turn to the first poem, if it doesn't appeal to you, you'll turn the page. You bought it, after all: you want to get what you can out of it. I don't think anyone likes everything they find in any one print magazine of any kind: if you enjoy forty to sixty percent of the content, you think it was worth buying. I have a hunch, though, that people are less forgiving with online magazines. If the first couple of posts are not to their liking, a lot of people will stop scrolling down and look elsewhere. Just as with the printed equivalent, to do so, I think, is a mistake.Of course, not everything's as good as it could be, any more than it is in the world of printed mags, but there are a lot of good online lit mags out there. It's right to mourn the passing of the golden age of the print-only version, but wrong to overlook what is perhaps a new, online golden age. There are too many to name: one has to go out there and search for oneself. I could make a list but, if you're not into online lit mags, I'd hate to deprive you of the fun of searching for them (while avoiding, if you're thinking of getting published, those that charge 'submission fees': vanity publishing is alive and well). If, like, I suspect, most people reading this, you're already into them, you'll have a mental list of your own.I could imagine, back in the days of Gutenberg, mourning the disappearance of works like the Lindisfarne Gospels (if, that is, I'd been lucky enough to actually see and been able to read them). Similarly, today, when I hold Ambit 75 in my hand, it's impossible not to think that something great has passed from the world (Ambit, sadly, came to an end in 2023). There again, when I check out my favorite online zines, it's obvious something equally worthwhile in its own way has come into it, too.I'll finish off with the first poem – I think – I ever got published in a printed poetry magazine, Mark Robinson's excellent (though now, sadly, defunct) Scratch back in 1995:

Ranter

Would they let him in?

He'd have to sound convincing. For a start,

he'd need a name - you know,

the sort that sounds

uncrackable, as if

he'd lived with it for years.

He'd need a reason, too.

This proved more difficult. It was not enough

to be the life and soul of the poem. They'd

see through that, they'd know

he'd almost certainly get pissed, then try

to set the universe to rights, grasping the sleeves

of exasperated punters. That's when

things always start to go wrong, he thought. In the end,

they'd have to throw him out.

"You bastards, I made you." He could hear himself slur, skidding

in a pool of his own vomit. "Where would you be

without me?" And then:

"I think we've had enough, sir."

"Bastards..." "Goodnight, sir."

Back to the street.

He'd have to think of something else.

He could make promises:

he'd keep his clothes on, only relieve himself

in the appropriate place, not puke

on the floor, keep his ideas to himself, even, though

what's the point? he thought. I'd

most likely break them, along with the glasses, and

perhaps it's not my sort of place after all.

Perhaps I just want to get out of the rain.

He might just take a bus instead.

Invent the route. Watch himself

stretched out across an empty seat

reflected in the darkness of the glass.

He might end up anywhere, might even rediscover

dragons

Dominic Rivron

Email ThisBlogThis!Share to TwitterShare to Facebook