The 19th century was a time of great change, and two cultural movements created dynamic tension throughout this fascinating period of world history. The Industrial Revolution transformed societies from agrarian economies to manufacturing economies within a few decades. Industrialization launched a dramatic increase in productivity and the standard of living for each country that became a part of the movement.

The Romantic Era, which peaked from 1800 – 1850, overlapped the Industrial Revolution. It was partly a reaction to the Industrial Revolution; poets, writers and musicians created an intense and emotional response to nature with emphasis on emotions such as horror, awe, and of course, romantic love.

(Get to the darned computers.)

(As soon as I finish showing off my degree in 19th century literature, dammit.)

So we have industrialists who are busy creating groundbreaking technology, and poets and writers who are busy creating some of the most imaginative and emotional art we’ve ever seen. Edgar Allen Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Percy and Mary Shelly, Keats, Walter Scott, Wordsworth, and of course, the iconic Lord Byron, who symbolizes the entire era.

Byron was an advocate of free love, and had multiple love affairs with men and women. Partly in order to save himself from himself, Byron married Annabella Milbanke, a reserved and mathematically gifted young woman from a wealthy family. In 1815, eleven months after their marriage, Annabella gave birth to a daughter named Augusta Ada Byron (who eventually became Ada King, Countess of Lovelace.) Shortly after her birth, Anabella separated from Byron, suspecting him of having an affair with his own sister. Ada, as she came to be called, never met her father, who died when she was eight. (He was 36.)

Ada’s mother raised her in a way she hoped would obliterate the influence of her poetic and dissolute father. She immersed her in mathematics and science, and Ada displayed great intelligence from an early age. She also rebelled against her mother’s refusal to let her pursue poetry. At the age of 12(!) she wrote to her mother: “You will not concede me philosophical poetry. Invert the order! Will you give me poetical philosophy, poetical science?”

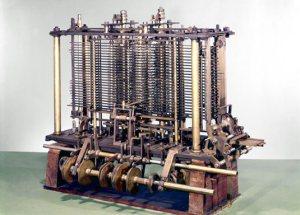

Ada grew up to have a mind that easily accepted both technology and poetry. At the age of 17, she attend a salon held by Charles Babbage, an inventor who demonstrated his Difference Engine, a calculating machine he was building. (see the nearby photo of a prototype built after his death.)

She once wrote: “Math constitutes the language through which alone we can adequately express the great facts of the

One of the characteristics that made Steve Jobs such a compelling figure was his obsession with beauty and design. Ada precedes him in her merging of the concept of technology and art. “I do not believe that my father was (or ever could have been) such a Poet as I shall be an Analyst; for with me the two go together indissolubly,” she wrote.

Walter Isaacson, who wrote Steve Jobs’ 2011 biography, includes Ada in his book. He writes: “[Ada] envisioned an attribute that might make [the Difference Engine] truly amazing: it could potentially process not only numbers but any symbolic notations, including musical and artistic ones. She saw the poetry in such an idea, and she set out to encourage others to see it as well.”

Maria Popova, writing for Brain Pickings, writes: “…she envisioned a general-purpose machine capable not only of performing preprogrammed tasks but also of being reprogrammed to execute a practically unlimited range of operations — in other words, as Isaacson points out, she envisioned the modern computer.”

Popova quotes Issacson at length to end her piece: “More than Babbage or any other person of her era, she was able to glimpse a future in which machines would become partners of the human imagination, together weaving tapestries as beautiful as those from Jacquard’s loom. Her appreciation for poetical science led her to celebrate a proposed calculating machine that was dismissed by the scientific establishment of her day, and she perceived how the processing power of such a device could be used on any form of information. Thus did Ada, Countess of Lovelace, help sow the seeds for a digital age that would blossom a hundred years later.”

I’d like to think that Ada and Steve Jobs found each other in the afterlife and are busy drawing up plans for some amazing personal devices.