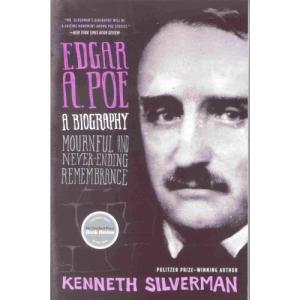

On his birthday I began reading a biography of Edgar Allan Poe. The last biography of Poe I read, I’m embarrassed to admit, was in high school. To me Poe is like music: deeply appreciated and therefore taken in rare doses. The biography this time was Kenneth Silverman’s Edgar A. Poe, A Biography: Mournful and Never-Ending Remembrance. I picked this book up last time I was on the University of Virginia campus, just after I stopped by to gaze wonderingly into Poe’s room. Like most biographies these days, Silverman’s account is hardly a hagiography. Poe was a perfect man only in his embodiment as a man of sorrows. In the days when “writer” was not really a profession, Poe nevertheless recognized what his strengths were and persisted to try to make a living following those assets. A poverty-stricken living much of the time, but an honest one. It is not pleasant to have a hero’s foibles exposed, but Poe was all the more admirable for having been fully human. We have all experienced arrogance and humility in turns. Poe was a man who knew sorrow from his youngest years, and that cloud stayed with him until his death just forty years later. A personal tempest.

On his birthday I began reading a biography of Edgar Allan Poe. The last biography of Poe I read, I’m embarrassed to admit, was in high school. To me Poe is like music: deeply appreciated and therefore taken in rare doses. The biography this time was Kenneth Silverman’s Edgar A. Poe, A Biography: Mournful and Never-Ending Remembrance. I picked this book up last time I was on the University of Virginia campus, just after I stopped by to gaze wonderingly into Poe’s room. Like most biographies these days, Silverman’s account is hardly a hagiography. Poe was a perfect man only in his embodiment as a man of sorrows. In the days when “writer” was not really a profession, Poe nevertheless recognized what his strengths were and persisted to try to make a living following those assets. A poverty-stricken living much of the time, but an honest one. It is not pleasant to have a hero’s foibles exposed, but Poe was all the more admirable for having been fully human. We have all experienced arrogance and humility in turns. Poe was a man who knew sorrow from his youngest years, and that cloud stayed with him until his death just forty years later. A personal tempest.

Poe, not a conventionally religious man, nevertheless recognized and drew upon religious imagery. In his poem “Ulalume—A Ballad” Astarte’s ghost appears. Astarte remains a goddess poorly understood, but Poe was likely drawing on her association with Venus. She fails, however, to lead to Heaven. Silverman points out how “Ulalume” was followed closely by Eureka, Poe’s only sustained attempt at metaphysics. Poe came to the conclusion that upon death we become part of the all-encompassing God. This daring deduction cost him friends and supporters, but it also led to a rebuttal by a seminary student. Poe’s reply to his criticisms remains apt, as Silverman quotes him, “‘God knows what’—he cared very little what he was called ‘so it be not a “Student of Theology.”’” Amen, Mr. Poe.

Some lives, like those of Job, seem fated to loss and suffering. Yes, there have been those who lost more than Poe, or even Job, but this is no contest to see who might bear the most weight before being driven to his or her knees. Poe felt it deeply and expressed it eloquently. He recognized, as most writers do today, that business models resent an honest voice. Those who sell are often those who pretend. I’m sure that Poe would nevertheless give a wry smile of irony if he knew how multiple editions of his works, long in the public domain, flow from the presses of publishers hoping to make a dollar or two on his now stellar reputation as a writer and, in full recognition of the paradox, a prophet. Like his raven, Poe could see beyond the confines of this world and paid the price for his vision. Obviously he was no student of theology.