On April 8, 1997, the government’s case against David Black was taken to a grand jury. Detective Joseph Fox had delivered an unusually tight case to Ken Whitted, the Assistant U.S. Attorney. Two months earlier, Alice Chow, an elderly activist in Washington’s Chinese community, had been gunned down in the 400 Block of K Street in Washington, D.C. Whitted inherited two witnesses who claimed to have witnessed the crime from the third and sixth floors of the Museum Square One apartment building. Larry Johnson and Barbara Marshall both saw David Black (they called him “Rob”) fire two shots at James Smith (they called him “June Bug”). One of those bullets, the government asserted, put Alice Chow in the grave.

As a consequence, David Black has spent a quarter century in the federal prison system.

By the time Larry Johnson finished his grand jury testimony, Ken Whitted had to know he was unreliable. In fact, Johnson’s relationship to the truth was so tenuous, the man had no place testifying to a grand jury.

Johnson was in the Museum Square One building illegally the morning Alice Chow died. He had been barred from the building (a red flag in itself), and faced several other minor charges. A court hearing had been scheduled a few days before the Chow incident, but Larry was a no-show.

Larry’s legal woes meant he couldn’t step forward as a potential witness without getting locked up. He won a few days freedom by identifying himself to Detective Fox as “Lawrence Thorne” instead of Larry Johnson.

Larry knew the police had no solid leads in the case. They might cut him some slack with the criminal justice system if he helped out. Larry wasn’t the most impressive witness; but the alternative was nothing.

Unfortunately, Larry didn’t have much to work with. Detective Fox was looking for a runner and a shooter. That’s all Larry knew. For the first six weeks, he never claimed to have witnessed the shooting, he just fed Fox-and-friends the names of possible suspects: June Bug, Little Anthony, Little Darryl. He couldn’t tell the police if June Bug was shooting at Little Anthony or if Little Darryl was shooting at June Bug, but he was trying.

In exchange for his assistance, Larry was placed in Hope Village, a massive halfway house. This allowed him to re-enter the free world during the day. He was expected to serve as a police informant, beating the streets for clues.

Six weeks after Ms. Chow died, an exasperated Fox, called Larry into his office, handed him a couple of pictures and asked if one of the men was June Bug. Larry then received a stack of eight cards; one of David Black, the others of people Larry had never seen. The name “David Black” didn’t ring a bell, but one of the pictures looked a lot like a guy who went by the street name “Rob”.

Then came the crucial question: Did Rob shoot at June Bug. Larry nodded.

Ten days later, David Black was arrested without incident and locked up. Larry was getting more restless by the day. He enjoyed a measure of freedom, but he wasn’t used to following somebody else’s rules. And once he had identified the runner and the shooter, he surrendered his leverage. He had nothing more to offer.

Larry was no stranger to the system. If he didn’t stick to his story, they’d nail him for perjury and obstruction of justice. The moment he signed onto the official story, the cops held all the cards.

So, one night in late March, Larry didn’t show up at the halfway house at the appointed hour. We don’t know how long he was on the lam, but as soon as the police took him into custody, he was hauled before the grand jury.

Larry had already met with Ken Whitted at least once and knew what he was expected to say. But it didn’t go well.

The problems began as soon as Larry was asked to describe the crime scene. He told the jury that, as he looked down from a third-floor window, Rob was no more than five or six feet away from him. In addition, he had June Bug running south across the crosswalk a few feet west of the apartment building. And he had Alice Chow in the same crosswalk as June Bug. He was running away from the building; she was walking toward it.

Larry seemed to believe that Lilly Memorial Baptist Church was just across the street from the Museum Square One Apartments; in reality, the church was over 200 feet to the west.

If Ken Whitted had read the police reports from the day of the crime, he would have known that Ms. Chow was within twenty or thirty feet of Lilly Memorial Baptist Church when she fell—a good 200 feet west of where Larry placed her.

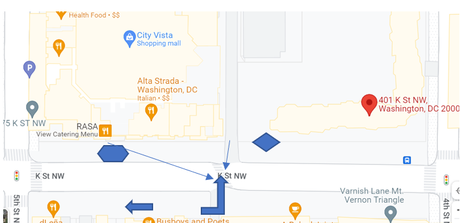

Moreover, according to the government’s theory of the crime, the shooter wasn’t in front of the apartment building; he was across the street from the Baptist Church. Perhaps a diagram might help:

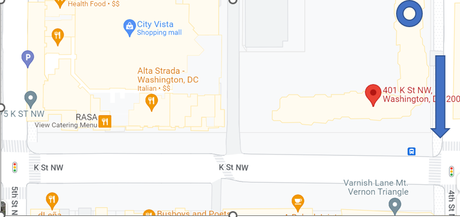

It got worse. The Museum Square One apartment building (401 K St. NW) dominates the corner of 4th and K Streets. Some apartments look out onto 4th Street; others are on the K Street side. When Whitted asked if the jurors had any questions, a confused juror asked a question that assumed the action took place on 4th Street (see map below) instead of K Street. “Right,” Larry replied.

This wasn’t a slip of the tongue. The juror asked his question a second time, still assuming that the shooting happened on 4th Street instead of K Street. Again, Larry confirmed his account.

At this point, it should have been obvious to Mr. Whitted that Larry couldn’t be telling the truth. Instead, he asked his star witness to confirm that he had been able to clearly see Rob and June Bug’s faces “when the incident happened.” Larry assured him that he could.

The juror who had Larry looking out onto K Street might have been on to something. If you Google 401 K Street NW (the address of the Museum Square One apartment building), the pin lands on the K Street side of the building. But if you add “apartment 305” to the search (Larry’s initial location), the pin jumps to the 4th Street side of the building. The same thing happens if you punch in “apartment 611” (Barbara’s room). Both rooms are located on the 4th Street side of the building.

Certain that this was just an odd anomaly, I called up Museum Square One. It’s a hard number to reach, but on my fourth attempt a receptionist answered. I told her about my Google search and asked if apartments 305 and 611 are on the K Street or the 4th Street side of the building. “Both those apartments are on the 4th Street Side,” she told me. I asked if she was certain. She was.

The implications of this brief conversation for the David Black case are enormous. Larry told the grand jury that he was first alerted to the incident on K street when he heard the sounds of an argument through the apartment window. Larry claimed that, when he heard the sounds of a scuffle on the street below, he glanced out the window. He could see two men standing beside a blue car, but he couldn’t see their faces. So, he walked down to the hallway window for a better view.

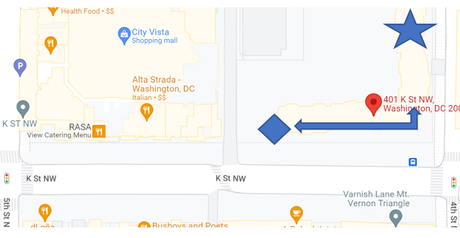

Larry couldn’t have heard a fight on K Street, and he certainly couldn’t have seen the action. Only by walking four hundred feet south and then west (see arrow above) could he have placed himself in a position to see anything.

Barbara Marshall’s case is equally problematic. She told the grand jury that she entered the hall when a neighbor, Reesey Green, knocked on the door (why, has never been clear to me). Barbara stepped into the hall and Reesey quickly retreated to her own apartment. That’s when Barbara glanced out the hall window and noticed two men arguing on the street.

Even these windows would have been at least 100 feet down the hall, but, even if Barbara had walked up to that window, she would have seen the corner of 4th and K Streets. Nothing to the west of 4th Street would have been visible.

It is true, of course, that both witnesses could have marched 400 feet down the hall to the only window that does provide a view of the crime scene. But both witnesses explained how they got to the window in question, and neither story made a lick of sense.

Larry’s grand jury testimony was horribly garbled because it bore no relation to reality.

In The Pilgrim’s Regress, an allegory by C.S. Lewis, a young boy is called in to speak to “the Steward”. The interview began with a pleasant chat about “fishing tackle and bicycles”. But the encounter took an ominous turn when the Steward plucks a “mask from the wall with a long white beard attached”, and “clapped it on his face.”

“Now I am going to talk to you about the Landlord,” the Steward said “in a queer sing-song voice”. After rambling on about how “very kind” the Landlord was, the Steward slipped the boy a card containing a list of rules and asked him if he had ever broken any of them.

“Half the rules seemed to forbid things he had never heard of,” Lewis tells us, and “the other half forbade things he was doing every day and could not imagine not doing.”

“John’s heart began to thump, and his eyes bulged more and more, and he was at his wit’s end when the Steward took the mask off and looked at John with his real face and said, ‘Better tell a lie, old chap, better tell a lie. Easiest for all concerned,’ and popped the mask on his face all in a flash. John gulped and said quickly, ‘Oh, no, sir.’”

This story comes to mind when I think of AUSA Whitted. He was just looking for two witnesses who were willing to repeat a specific mantra. They didn’t have to believe it. He didn’t have to believe it. They just had to say it so the public could be satisfied that justice had been served. And they did. Except when they didn’t . . . but that story is for next time.