In a near perfect follow to my recent post on animist and quantum worldviews, Margaret Wertheim explains why physics — supposedly the most “hard” of all sciences — is bedeviled by difficulties. It is a lucid, patient, and brilliant piece of writing on a subject that is, for most of us, difficult. Despite the difficulty, Wertheim hits on all the key issues, beginning with her observation that physics is essentially Platonic:

Most physicists are Platonists. They believe that the mathematical relationships they discover in the world about us represent some kind of transcendent truth existing independently from, and perhaps a priori to, the physical world. In this way of seeing, the universe came into being according to a mathematical plan, what the British physicist Paul Davies has called ‘a cosmic blueprint’. Discovering this ‘plan’ is a goal for many theoretical physicists and the schism in the foundation of their framework is thus intensely frustrating. It’s as if the cosmic architect has designed a fiendish puzzle in which two apparently incompatible parts must be fitted together.

Equating physics with Plato may seem, at first blush, a bit odd. Plato is usually associated with the non-physical (or imaginary) world of ideal forms. According to Plato, these perfect or essential forms — which cannot be perceived — constitute the real or actual world and everything else, including all perceptions, is an imperfect reflection or facsimile of the forms. This is a quintessentially metaphysical viewpoint that lends itself especially well to religious thinking. Recognizing this, early Christian intellectuals imported Plato nearly wholesale into that tradition, a fact which prompted Nietzsche to quip that “Christianity is Platonism for the people.”

But if we reverse this common understanding of Plato, we can also see him as establishing a framework within which science could operate. As philosopher Scott Berman explains, we can also see Plato as a naturalist:

Plato took himself to be arguing that unless his view is right, science is not possible. The fact that we do have science now is confirmation that Plato was right, or so I think anyway. He thought that unless there exist things that can never change, there can’t be objects that are stable enough for knowledge, i.e., science. And so, he argued against Nominalism, that is, the idea that all that exists are spatiotemporal things, and Constructivism, that is, the idea that the measures or criteria of what things are can change. He argued that if there exist non-spatiotemporal things, then such things could be the objects of science and hence that science is possible. Laws of natures, for example, would be non-spatiotemporal things according to Plato and so aren’t located anywhere (because they are non-spatial) and can’t change (because they are non-temporal). If there truly is a science of some subject matter, then there has to be a non-spatiotemporal thing which is the measure of that subject matter.

With this, we can better understand why Wertheim contends that most physicists are Platonists. This is somewhat ironic, given that physics is usually considered the “hardest” or most real-material of sciences. Yet there is a tension here because physics starts with an assumption (i.e., that mathematics does not simply describe or approximate reality but actually constitutes it) which is thoroughly metaphysical. While modern physicists have attempted to separate their science from theology, these foundational assumptions may always lead them back to metaphysics. As Wertheim explains, this is partly a matter of history (it’s also partly a matter of method):

In its modern incarnation, physics is grounded in the language of mathematics. It is a so-called ‘hard’ science, a term meant to imply that physics is unfuzzy — unlike, say, biology whose classification systems have always been disputed. Based in mathematics, the classifications of physicists are supposed to have a rigour that other sciences lack, and a good deal of the near-mystical discourse that surrounds the subject hinges on ideas about where the mathematics ‘comes from’.

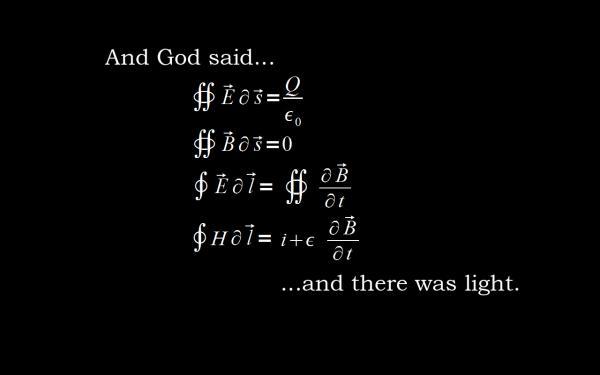

According to Galileo Galilei and other instigators of what came to be known as the Scientific Revolution, nature was ‘a book’ that had been written by God, who had used the language of mathematics because it was seen to be Platonically transcendent and timeless. While modern physics is no longer formally tied to Christian faith, its long association with religion lingers in the many references that physicists continue to make about ‘the mind of God’, and many contemporary proponents of a ‘theory of everything’ remain Platonists at heart.

Having kicked metaphysics and theology out the front door, physicists often bring them right back in through the rear. If you’ve ever wondered why theoretical physicists talk in ways that sound religious or mystical, this is the explanation.

This also explains why I have asserted a similarity between animist and quantum worldviews. At these ultimate or foundational levels, theoretical physicists talk in ways and describe things that may or may not be true, correct, or real. We don’t know and they don’t either.

But these descriptions are not at all unlike, and indeed are quite similar to, animist descriptions of the way things work. I am not asserting these worldviews are ultimately correct, only that they are — despite different idioms — structurally and functionally similar. By this conception, it is difficult to describe (or marginalize) animist worldviews as the product of “primitive” minds or cultures.

All this aside, be sure to read Wertheim’s piece. She deploys Mary Douglas’ Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (1966) in a particularly fruitful way. Despite having read Purity and Danger, I didn’t much care for it. Wertheim’s use of Douglas suggests that I may need to revisit it.