Peter Pauling with his parents, ca. 1950s.

“This tub moves steadily but slowly along.” So wrote Peter Pauling in a letter to his mother, Ava Helen Pauling, riding somewhere in the Atlantic in the hull of a cargo ship that had been built in 1926. “It took us two and a half days to reach the open sea.”

Having said goodbye to the nightlife of Montreal, and having entrusted his brother Crellin with the needle to his old turntable, Peter took to the sea without much to his name save a bottle of duty free Canadian Rye Whiskey; which, he lamented, did not keep him as warm onboard the cold ship as a good overcoat might have done. (Ava Helen, ever concerned for her son’s well-being, would see to it that he would have money to pick up some warmer clothes once he had arrived in Cambridge, paid for in matured war bonds.) Onboard the ship, Peter shared his cramped cabin space with three roommates: a Scot, a “very pleasant and hard-working” Englishman, and an 18 year old “pipsqueak” just out of rugby. Ever the charismatic socialite, Peter must have been excited to spend his days at sea with such an assortment of characters.

Arriving in England in the fall of 1952, Peter began his studies at Cambridge University, working under John Kendrew, a Peterhouse Fellow in Max Perutz’ Molecular Biology Unit at the Cavendish laboratory for physics. Although the Cavendish traditionally had not extended its focus beyond physics and physical chemistry to questions of biology, Sir Lawrence Bragg – director of the Cavendish and chair of the university’s Physics department – had recently supported an expansion of the lab’s scope to include the mapping of biological molecular structures.

This new Molecular Biology Unit would spearhead several important discoveries, among them Kendrew’s and Perutz’ work on the atomic structure of proteins, the program of research that Peter was brought on to support and an accomplishment significant enough to garner the 1962 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. That same year, two other former Cavendish researchers – James Watson and Francis Crick – would receive their shared Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discovery of the double helical structure of DNA, a breakthrough that Peter Pauling certainly observed from a front row seat, and even, perhaps, helped to make possible.

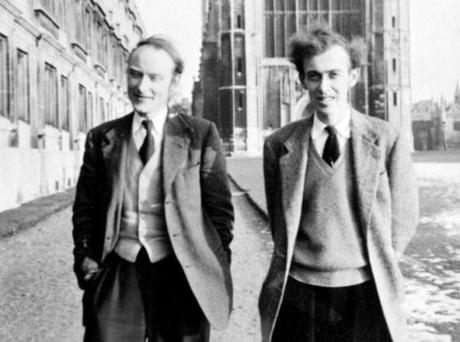

Francis Crick and James Watson, walking along the the Backs, Cambridge, England. 1953. (Image Credit: The James D. Watson Collection, Cold Springs Harbor Laboratory Archives.)

When Peter Pauling first moved into the office that he shared with James Watson, Francis Crick, and Jerry Donahue, Watson noted that Peter was “more interested in the structure of Nina, Perutz’s Danish au pair girl, than in the structure of myoglobin.” Crick, too, felt that the young Pauling was “slightly wild,” but still the office mates hit it off immediately. According to Watson, Peter’s presence meant that, “whenever more science was pointless, the conversation could dwell on the comparative virtues of girls from England, the Continent, and California.” Watson and the young Pauling even made a point of visiting The Rex art house cinema together to watch the 1933 romantic film Ecstasy, which Watson referred to affectionately as, “Hedy Lemarr’s romps in the nude.”

Women aside, Peter was most concerned by the day-to-day troubles that were typical of English life in the early 1950s. He wrote to his mother about the lack of a bathtub in the small, cold, damp room that he now inhabited, and complained about the space’s perpetual lack of sunlight. He did praise his fortune at having scoured London and finding a suitable teapot, and he requested that Ava Helen kindly make him a pair of curtains for his window (which she happily obliged).

In letters to his father, Peter preferred to talk about cars, or his recent dinners with the Braggs and their daughter Margaret, rather than his own research pursuits. Linus, on the other hand, was immediately curious about the intellectual climate at the Cavendish and was especially interested in the work of Francis Crick, who a year earlier had been part of a collaborative effort to develop a theory of mathematical representation for x-ray diffraction that was fast becoming a standard in the field.

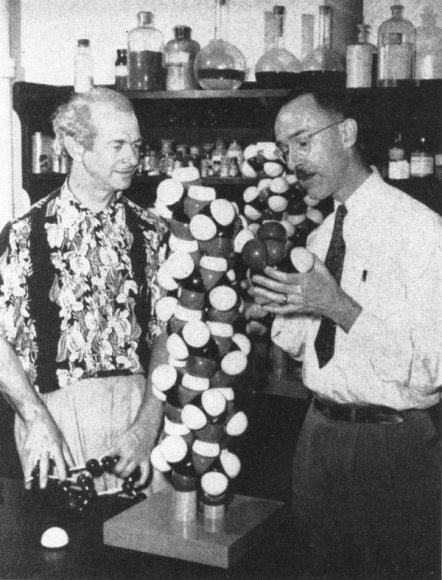

Linus Pauling and Robert Corey examining models of protein structure molecules. approx. 1951. (Image credit: The Archives, California Institute of Technology)

The previous year, 1951, Linus Pauling had bested Bragg and the physical chemists at Cambridge in becoming the first to publish the alpha helical structure of many proteins. Despite the desire prevailing at the Cavendish to eventually beat Linus Pauling at his own game, Watson and Crick had been warned to keep away from the study of DNA by the head of the lab. Bragg knew that Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin, of King’s College London, were already working on the problem using Franklin’s photos and crystallographic calculations of the A and B forms (low and high hydration levels, respectively) of DNA.

Wilkins’ and Franklin’s work was proceeding slowly, however, and Peter Pauling and Jerry Donahue – another Caltech graduate now stationed overseas as a post-doc – were both in regular communication with Linus Pauling. These contacts provided Watson and Crick with insight into what was going on in Pasadena. In his correspondence, Peter joked about the mounting competition between Caltech and the researchers at the Cavendish and King’s College. “I was told a story today,” he said to his father. “You know how children are threatened ‘You had better be good or the bad ogre will come get you?’ Well, for more than a year, Francis and others have been saying to the nucleic acid people at King’s, ‘You had better work hard or Pauling will get interested in nucleic acids.'”

While Watson and Crick urged Wilkins to provide them with Franklin’s images and calculations so that they might model the structure themselves, Peter stoked the fires of their urgency, assuring them that his father was no doubt only moments away from solving the problem. Donahue was equally convinced: for him, Linus Pauling was the only scientist likely to produce the right structure.

By December, the fate that Jerry Donahue and Peter Pauling had been predicting seemed to come true: a letter from Linus to his son claimed that he had indeed determined the structure of DNA. The letter gave no details, simply confirming for Watson and Crick that Pauling and his Caltech partner Robert Corey had somehow solved the problem. Watson later recounted his colleague’s distress in hearing this news, recalling that Crick “began pacing up and down the room thinking aloud, hoping that in a great intellectual fervor he could reconstruct what Linus might have done.” But it seemed to be too late. Pauling’s DNA paper was set to appear in the February 1953 issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. In all likelihood, it would be time to move on to new projects.