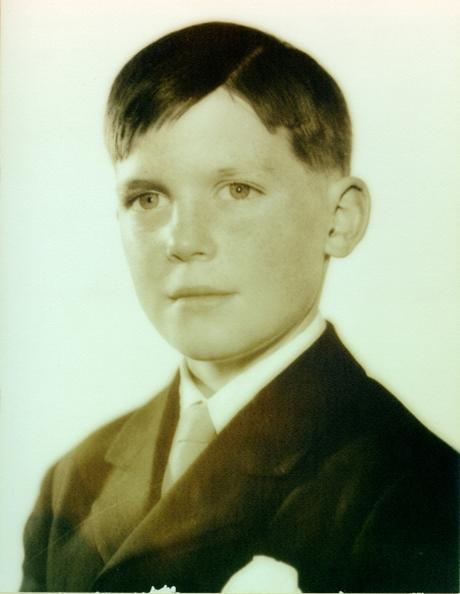

Linus Pauling with his second-born son, Peter. 1931.

[Ed Note: Today we begin an in-depth examination of the life of Peter Pauling, the second child born to Ava Helen and Linus Pauling. This is part 1 of 9.]

Peter Jeffress Pauling was born on February 10, 1931. His middle name was given in honor of Lloyd Jeffress, his father’s childhood friend, fellow undergraduate at Oregon State (then the Oregon Agricultural College), and best man on his wedding day. Peter was the second born of the Pauling children. His older brother, Linus Pauling, Jr., was born in 1925, and Peter was joined swiftly by his younger sister Linda Helen in 1932 and, finally, by the baby of the bunch, Edward Crellin Pauling, in 1937.

In the early 1930s, everything seemed to be falling into place for the Pauling family. The same year that Peter was born, his father was promoted to full professor at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, where Linus had been since 1922, completing his doctorate the same year that Linus Jr. was born.

The growing family moved into a new home on Arden Road shortly before Peter’s birth, a transition that provided more space for the children and for their dog, Tyl Eulenspiegel, a cocker spaniel named after a German comic character. The year 1931 also marked Linus’ first published article on the nature of the chemical bond – work that would ultimately result in a Nobel Prize.

In the decade following Peter’s birth, his father was incredibly busy, giving fourteen guest lectures at Berkeley alone before Peter turned three. He also publishing his revolutionary structural chemistry research in a groundbreaking book, 1939’s The Nature of the Chemical Bond, a text authored while Pauling was in the midst of a series of nineteen non-resident lectures at Cornell.

Ava Helen Pauling with her infant son, Peter. 1931.

By the time of the book’s publication, Linus Pauling was becoming a meteoric scientific figure, and as he began to travel more frequently, his wife Ava Helen would increasingly accompany him. During this period, the three youngest children – especially Linda and Crellin – were often in left in the care of a woman named Arletta Townsend, who became something of a second mother to them in their youth. The oldest child, Linus Jr., also shared in the care of his younger siblings from time to time, frequently trundling little Peter around the front yard in a child’s red wagon (perhaps an early indicator the boys’ shared love of automobiles that would bring them together later in life).

The older children also cared for the family rabbits, which their father raised at home for future use in his research. What was, for the children, a chore was also a reflection of Linus Pauling’s growing fascination with serology, hemoglobin, and the formation of antibodies and their interaction with antigens. As his investigations moved forward in the late 1930s and early 1940s, Pauling found it either impractical or inconvenient to arrange for his study animals to be housed and tended at Caltech. He opted instead to build roughly fifty rabbit hutches on his own property. While the elder Pauling inoculated the rabbits and carefully recorded physiological data, his boys were charged with feeding, watering, and keeping the hutches clean.

At this time, Peter seemed to have little in common with his older brother, outside of their shared chores around the house. Looking back, Linus Jr. would remember that most of their interaction was restricted to fighting over the bathroom. An argument over this space once became so heated, that it resulted in Linus Jr. splintering a door frame in the scrum.

Peter Pauling with his father, 1937.

The United States’ entry into the Second World War touched the lives of all the Pauling children in different ways. In 1937, when Peter was six, an Army rifle range appeared on the other side of a canyon near the Pauling’s new home on Fairpoint Street. With this facility came a small group of Army guards, who would stand vigil near the Pauling’s property. Over time, the soldiers emerged as a social outlet for young Peter, who even as a child seemed to have a natural charm that often brought him rewards. For several years, Peter used the sentries as a means for procuring souvenirs and even stray military equipment. Many years later, much of this treasure could still be found in storage at the family ranch near Big Sur, California.

Not only was Peter charming, he was quite intelligent as well. From 1936 to 1941, Peter attended Polytechnic Elementary, a private school in Pasadena. A 1937 report on his performance included the comment that he was, “Not only a superior child in intelligence, but one of the cutest children we ever took into the school.” Two years later, the praise had only grown – one educator wrote that Peter “seems to be his Daddy’s own boy, and that is saying a great deal.”

From early on in her children’s lives, Ava Helen harbored ambitious ideas for the pursuits that they should entertain, and Peter was identified as the child most likely to succeed in a career in science, thus following in his father’s massive footsteps. Later in life, Linus himself would make passing insinuations about their potential as a father and son scientific duo, referencing the notable case of William and Lawrence Bragg, who shared the 1915 Nobel Prize in Physics for their work on x-ray crystallography. Peter would later become well acquainted with Lawrence Bragg and his wife during his stint at Cambridge, a time period during which Peter had begun actively pursuing his own career in physics and chemistry.

The Pauling family with their rabbits, 1941. Peter stands at left.

In 1941, after Peter had completed his fifth year at Polytechnic, Linus and Ava Helen concluded that their gifted son had started to lag academically. To provide for a more effective learning environment, the Paulings had Peter – now ten years old – enrolled at Flintridge Preparatory School in Pasadena. Flintridge was a school for boys where Peter would live in a dormitory, his days closely supervised and specifically structured according to a daily schedule that ran from 7 am to ‘lights out.’

At Flintridge, pupils were allotted one hour and forty five minutes of leisure time per day, with any other time not spent in class devoted to eating, completing chores, playing supervised sports or performing other physical exercises, or studying (also supervised).The school tailored its curriculum to the expectations of a student’s desired college or university, all with an eye toward insuring that the student would be best prepared to pass entrance exams or to enter a university without taking the exams at all.

The school’s all encompassing tutelage embraced a three-fold training style that aimed to educate the mind, body, and the spirit, as evidenced by its motto, Vires Corpore Mente Spiritique. To chart the progress of the body, Peter’s performances in a range of physical activities – from running and high jump to shot put – were recorded and graphed over the course of the year. These data were then charted against an average representing the capacity of most boys his age, a practice referred to as a Physical Quotient plan. According to an informational pamphlet published by the school in 1941, Flintridge was the only school for young men in existence at the time that adhered to such a plan. The outcome, it promised, would be young men driven to develop their posture and muscle skills.

Once Peter was enrolled, his parents were issued monthly reports on their son’s progress, and to their pleasure, Peter’s schoolwork showed measurable improvement. Unfortunately, the decision to move Peter to Flintridge caused Polytechnic to withdraw its provision of scholarships for the remaining Pauling children. These scholarships had been provided with the contingency that the three eldest Pauling children attend the school, but with Linus Jr. completing his education at Polytechnic and Peter moving on to a different school, it was no longer deemed appropriate to provide a scholarship for Linda alone. As a result, young Linda Pauling was no longer able to attend private school at Polytechnic.

Peter Pauling, 1943.

The summer months following Peter’s first year at Flintridge were spent, by Linus and Ava Helen, mostly abroad. As a result, the three youngest children were sent off to Camp Arcadia at Big Pines Park, California, while Linus Jr., now 16, was allowed to remain at home. While at camp, Linda became ill and had to be sent home a month early, leaving Peter and Crellin – from their perspective – stranded at the camp and feeling homesick. Linus Jr. wrote to Peter at this time, urging him to appreciate the time away from the mundane concerns of the Pauling home, including the return of parental discipline. “They’ve found all the things I didn’t do and should have done, and all the things I did do and shouldn’t have done,” Linus Jr. wryly confessed to his younger brother.

In 1943, when Peter was 12, Linus and Ava Helen received letters from his teachers at Flintridge explaining that Peter’s ability to excel seemed increasingly beset by an inability to focus on his work. The staff believed that Peter, like many intelligent children, was not being challenged enough academically, and that in his boredom he preferred to spend his time socializing rather than studying.

Perhaps only coincidentally, this was the same year that Peter’s older brother turned eighteen and left home for Berkeley. While Peter was being groomed in hopes that he might emerge as the next genius of the family, his older brother, Linus Jr., deliberately turned away from any such prospect as he entered adulthood, eventually abandoning college aspirations altogether and joining the Army Air Corps during World War II.