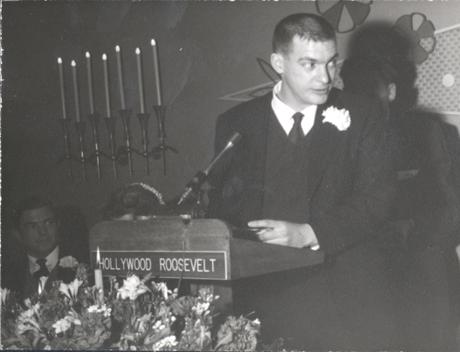

Peter Pauling, speaking at his father’s sixtieth birthday party, Los Angeles, 1961.

[The life of Peter Pauling, part 7 of 9]

Journeying on their honeymoon through the caves of northern Spain, Peter Pauling and his wife Julia arrived at a small fishing village and made camp. His beard full and his hair grown to nearly his shoulders, Peter sat on the beach, scouring pots. Meanwhile, Julia watched the water, contented by the meal that she had just prepared for her new husband. She had always loved the sea, saying as much in her letters to Linus and Ava Helen Pauling, her new parents-in-law.

Julia had been a bright student at Cambridge. An avid reader of French and German literature, she was once hailed as the year’s best student at Girton College and had received the highest marks possible in her first year examinations, an achievement that surely would have impressed Linus and Ava Helen. Given the circumstances of their marriage however, Peter and Julia had their work cut out for them in attempting to smoothing things over with both sides of the family. As she attempted to do so in her communications, Julia was especially complimentary of the Paulings’ new property at Big Sur. In particular, she swooned over the “heavenly” view of the Pacific Ocean, as observed from the coastal bluffs of California.

Upon their return to London, the pair moved into their new home in Clapham, which Peter described as “an ugly Victorian suburban house that ought to be quite pleasant.” Many things changed for Peter as he settled into his new life. With the help of his mother and younger brother Crellin, he shipped his Mercedes back to the United States where it would eventually be sold. He had likewise traded in his most recent automotive conquest, a Porsche, upon his and Julia’s return from their honeymoon. The proceeds from these sales and trades were used – with added financial help from Peter’s parents and his older brother Linus Jr. – to purchase a new home for the family at Lansdowne Road.

By July 1956, Peter and Julia were thinking of names for their baby, with Peter being “most uncooperative about this business,” according to his wife. In her letters to Ava Helen, Julia noted that every time she suggested a reasonable name, Peter demurred, offering alternative suggestions like “Gregorio” and “Plug-up,” the latter a character from what Julia considered a “pointless space-fiction strip cartoon.”

When finally the baby came on August 22, the pair had settled their differences. Peter Andrew Thomas Pauling, to be called Thomas, was born that summer, to be followed by a younger sister, born February 5, 1960. Again there seems to have been some measure of disagreement about a name, with Peter first announcing his daughter to his parents as “Esmiralda Ermitrude.”

That name didn’t stick, however, and within a month, Peter was writing to his mother and father that their new granddaughter, Sarah Suzanne, had begun to smile and sleep all night. It was one of many letters in which Peter expressed joy at being a father. Within five years, Peter would excitedly report that Sarah was reading bedtime stories to him, rather than the other way around. By this time, young Thomas was at the top of his class as well.

Peter and Julia enjoyed a great deal of support from friends and family during these early years. Typically, the couple would spend the Christmas holiday season with Julia’s parents in the north of England, while the Pauling family would usually visit at various points throughout the year. Occasionally, Peter’s sister Linda and her husband Barclay would see the young family, bringing their twin boys “Barkie” and “Sasha” in tow. Linus and Ava Helen often came through London while on European trips for conferences, bringing with them comfort items from the States as well as more important cargo, such as the polio vaccine.

Thomas and Dorothy Hodgkin stopped in regularly, as did the Cricks and the Bernals. Joy and J.D. Bernal gave Thomas his first toys and provided the cake for Sarah’s first birthday party. The Hodgkins offered Peter and Julia their old baby bath, and Francis and Odile Crick passed along some hand-me-down clothes. “So far,” Peter joked, “the entire cost of the baby has been one box of chocolates for the nurses.”

Even Jim Watson dropped in, meeting young Thomas, who loved to turn all the knobs on a sprawling electronic gramophone that Peter had pieced together from spare parts. The room was a hopeless mess, Watson noted, and surely the bane of Julia’s existence. On top of that, Thomas’ interventions generally scrambled the music until it was incomprehensible.

Buoyed by a little help from his friends, Peter’s career took a positive turn as well. Lawrence Bragg had agreed to take Peter on at the Royal Institution for three months, in order to allow him to finish his degree. When three months turned out to be not enough time, Bragg and John Kendrew conspired with their colleague Jack Dunitz to obtain for Peter a position as a research student, working under R.S. Nyholm at University College, London. Once there, Peter would be allowed to continue his education while simultaneously collaborating with Dunitz to complete his research.

The arrangement worked. Peter switched the focus of his dissertation from protein crystallography to inorganic molecules, using x-ray diffraction to verify configurations of a halide compound, NiCL4. Peter likewise worked with a number of other transition metals, performing stereochemical experiments to determine their atomic structures.

At the same time, Peter began working with his father to develop a theory of the molecular structure of water, a subject on which he had spoken at a meeting of the Royal Society in 1957. After the two Paulings developed their theory, which postulated a random dodecahedral structure for liquid water, Peter became quite prolific. Throughout the late 1950s and 1960s, he published just over thirty papers, including fourteen in 1966 alone.

He also became much more active in the field, flying often to the United States for meetings of the Crystallographic Association, as well as other conferences in locations from San Diego to Denver to Pittsburgh. Having completed his PhD in 1959, Peter was immediately offered a lectureship in Chemistry at University College. And though he continued to muse in his letters to Ava Helen that he really didn’t want to do chemistry forever, he quickly accepted the position.

Julia and Peter Pauling at the 1963 Nobel Peace Prize ceremony in Oslo.

At long last, Peter seemed finally to be stepping out from his father’s shadow. And importantly, one sign of this transformation was his own realization that he was not, and could never be, the chemist that Linus Pauling was.

Instead, Peter began to focus his efforts on computers and other electronic systems valuable to the lines of chemical research that he had been pursuing. Among the rash of papers that he published in 1966 was “A Program for the Use of Large Computers for Crystallographic Problems,” which appeared in the British Journal for Applied Physics. Here, Peter was finally in his element, working at the forefront of a field that was swiftly changing, engineering devices by hand, and building complicated electronics systems such as a “one dimensional diffractometer” for x-ray crystallography – or what Peter called an “automatic gadget” – from plug-in logical blocks.

Peter took the first steps toward an important milestone in this new line of research, when he ordered a computer and electronic parts that he thought would be necessary to produce a copy of the state of the art diffractometer and visualization systems then in use at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the American research center founded in 1942 as part of the Manhattan Project. Funded by a Public Health Service grant, his system-in-progress deployed an ex-military scope equipped with a preamplifier, a Schmitt trigger, a monostable pulse generator (used to trigger the scope), and a Sherwood FM tuner that he had acquired from Linus Jr. The tuner in hand, Peter spent almost a year tracking down its circuit diagrams, so that he could most effectively cannibalize it in support of his cobbled together atomic measurement machine.

Once completed, not only did Peter’s device work, it worked marvelously. By May 1968, his computer and the program that ran it were making thousands of minute measurements per week. Indeed, the apparatus was used to determine the structure of five compounds in a ten-week period; a volume of calculations, as Peter pointed out, that was visually represented by four miles of punched paper tape that the computer had to read in producing the work. This huge success stood in stark contrast to Peter’s years at Cambridge, where he had struggled mightily to adequately determine the structure of a single compound.

With his machine, Peter Pauling was attempting to make University College technologically competitive with an institution that had received major support from the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission during the height of the Cold War. Astoundingly, he accomplished this goal using, to a large degree, spare parts. Later, Peter would use the measurements from his device to improve the Caltech method for drafting pseudo-perspective drawings of molecular structures, producing instead Third Angle Projection-style drawings of atoms and their bonds. As his successes mounted, he was promised a lab that would be four times larger, and was elected President of the Chemical and Physical Society of University College, London.

Behind the scenes, however, Peter was struggling to balance his career with his family life, and was plagued by personal demons. Ever since leaving Cambridge a decade earlier, his mother had been worried about his mental health, urging him to see a psychiatrist about his struggle with manic-depression. Over time, this view came to be shared by a growing number of friends and family. But burdened as he was by the competing forces of a new wife and children, the completion of his degree, and the press of research and professional obligations, there never seemed to be a good time.

At one point, Linus Pauling became so concerned for the welfare of his grandson, Thomas, that he offered to arrange for the boy to live in Pasadena for as long as might be necessary for Peter’s domestic situation to stabilize. Peter responded that he was far too busy writing his thesis and preparing lecture courses at University College to fly Thomas to New York. A few months later, he revealed that Julia was pregnant with their second child.

As time passed, the growing strain on Peter and Julia’s marriage became palpable to those who knew and loved them both, and by 1961 Peter had suffered a serious breakdown, confiding to his parents that he was finally and earnestly trying to see a psychiatrist, as his bouts with sadness had become “uncontrollable.” Peter’s lament seemed, at times, to mirror the dark geopolitical climate of the 1960s. After John F. Kennedy’s assassination, Peter wrote to his mother that he was “stricken” by the President’s death. The optimism of the Kennedy years had led him to think that “ordinary mortals” might “rest a little easier” under the vibrant president’s leadership. “Now,” Peter admitted, “I fear it is back to the struggle.”

But as the decade moved forward, Peter Pauling found that he had other struggles of his own to worry about. By 1967, he and his wife had agreed to a divorce. Peter subsequently moved into a flat in dodgy area of London – St. John’s – where he shared his new space with a painter. The flat was later robbed, and Peter lost most of his clothes and jewelry, as well as his radio, as loss that he lamented. (“I used it all the time,” he wrote, “to fill up the empty holes in my head when I am alone.”) Likewise stolen was a pot that his sister Linda had given him for Christmas. He wrote to her that he missed this item the most, as it meant more to him than anything else that was taken.

Linus Jr. came to London to visit his brother during this time, and ultimately left the scene both worried and relieved. The worry came from the fact that Peter, by his own admission, was drinking and smoking far too much. On the other hand, Linus Jr. felt a measure of relief that his brother had finally done what he thought was right for his children: leaving the family home at Lansdowne Road to Julia, Thomas, and Sarah.