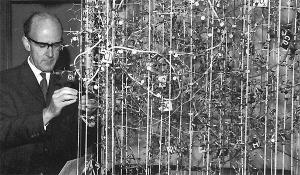

Perutz with his hemoglobin molecule, 1959. Image credit: Life Sciences Foundation.

[Part II of our survey of the life of Max Perutz, this time focusing on the years 1941-2002. Published in commemoration of the Perutz centenary, May 2014.]

Knowing that his parents were safe from Nazi persecution and able to return to the United States, circumstances began improving for Max Perutz. The Rockefeller Foundation reactivated his grant, allowing him to support himself while stateside as well as his parents in Cambridge, England. Perutz’s father was also able to find work as a laser operator during the war and afterwards qualified for a pension.

In September 1941, Perutz met Gisela Peiser, who was an accountant at the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning, an organization that assisted Jewish and other academic refugees fleeing from the Nazis. After a quick courtship, they were married the following March and, in December 1944, welcomed their daughter Vivien into the world. That same year, Perutz also found himself back in good stead with the British government and recruited to research ice strength for potential ice stations in the North Atlantic. The research did not work out, so Perutz returned to his work on hemoglobin at Cambridge. The next few years were spent trying to put together a secure source of income for him and his growing family. In the interim, he took out more loans and found a temporary fellowship.

Meanwhile, Perutz’s health continued to suffer. As his chronic gastrointestinal attacks became more unbearable, interfering with his daily activities more and more, Perutz began to seek out help. Most doctors he saw told him it was a psychological problem, but eventually one doctor recognized that the symptoms could be treated by a mixture of atropine and codeine. The remedy helped enough for Perutz to live more or less undisturbed by the problem for several years, though eventually that would change.

Perutz and John Kendrew, 1962. Image credit: Nobel Foundation.

In 1947, the war now completed, Perutz, along with John Kendrew, was appointed to head the new Research Unit for the Study of the Molecular Structure of Biological Systems (Perutz later shortened the unit’s name to Molecular Biology Research) at the recently established Medical Research Council. Situated at the Cavendish Laboratory in the physics department, the group expanded on Perutz’s earlier application of x-ray crystallography to biological materials. Perutz, in this new administrative role, described his lab management as one where he would “leave people free to do what they wanted…if they were good scientists.”

One of the several student researchers that came through the lab was Francis Crick, who started work in 1949. Perutz had Crick look at the validity of his hemoglobin model, which was the culmination of roughly six years of research. Crick applied his mathematical training to show that the model was “nonsense.” Perutz accepted Crick’s assessment and later reflected that only in England at that time could a student be so critical of their principal investigator. Crick was eventually drawn away from hemoglobin research by James Watson, who came to the lab in 1951 to work under Kendrew on molecular structure, but his impact on the development of Perutz’s hemoglobin structure was long-lived.

Throughout the late 1940s, Perutz also continued his work on glaciers in the Alps and helped found the Glacier Physics Committee in 1947. Though he had trouble recruiting able assistants who could also ski (the first two broke their legs), the work gave Perutz and his family the opportunity to spend summers in the mountains. Perutz’s research led him to conclude that glaciers flowed faster at the surface than at the bottom.

Perutz’s digestive attacks began increasing in intensity in the early 1950s to the point where, in 1954, he was hospitalized for ten days. While there, doctors looked for possible causes but came up empty and could only prescribe bismuth, with little effect. What did help, for reasons Perutz did not understand, was visiting the Alps, and so he arranged for a trip after being released from the hospital. Unfortunately the attacks resumed as soon as he returned to Cambridge, pushing Perutz to his limits – he considered resignation and even contemplated suicide. In desperate straits, he arranged for another trip to the Alps that spring but, once there, continued to get worse and, as an added complication, came down with scurvy.

When he returned, Perutz sought out other doctors who might be able to help, eventually visiting Werner Jacobson, who was also at Cambridge. Jacobson thought Perutz’s symptoms sounded like those of Celiac disease. He suggested that his patient stop eating wheat, or more specifically gluten, which immediately improved Perutz’s condition. Whenever the symptoms appeared again, as they did in the early 1960s, Perutz could trace them back to gluten; he eventually stopped eating any form of bread, since even gluten-free flour contained small amounts of gluten that negatively affected his health.

Perutz in lecture. Image credit: Nature.

Perutz’s improved physical condition coincided with the final years of his triumphant work on a determination of the structure of hemoglobin. After working out a solution to interpret x-ray diffraction photos of proteins three-dimensionally, Perutz came upon the structure in September 1959, submitting his findings to Nature before heading to the Alps to ski over the winter break. By the time he returned, he was famous. It was quickly and widely acknowledged that his work comprised a major breakthrough for both chemistry and biology. As Hugh E. Huxley wrote, in 2002

He was the first person to find out how to determine protein structure by X-ray crystallography, after many years of patient struggle, and he applied the technique to solve the structure of haemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein in blood….The results showed that it was possible to see, in the atomic detail necessary to understand mechanisms, the structure of the macromolecules that carry out many of the functions of a living cell. Such knowledge is basic to the revolution that has swept through biology in the past 50 years, and to modern medicine and biotechnology.

By Fall 1962 there were rumors that Perutz would be awarded the Nobel Prize for chemistry. As October arrived, he began receiving calls from the press, but did not quite trust them. As the calls continued, Perutz received a telegram and thought, along with the rest of the lab, that it may be from the Nobel committee. Alas, the message was only from Nature asking how many reprints of his article Perutz wanted. That afternoon however, Perutz received another telegram, the one he had been waiting for. The lab celebrated with a champagne party as Perutz and Kendrew had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, and Watson and Crick, along with Maurice Wilkins, would receive the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine.

Perutz continued to work on the hemoglobin structure after his rise to fame, next turning to the question of how the structure changed with the uptake of oxygen. His Nobel lecture described this continued research on the four subunits within hemoglobin that changed their structure as oxygen was taken up; the first description of how proteins changed in structure.

In the years that followed, Perutz focused more on why this change occurred. Aided by automated x-ray diffraction machines and able assistants, Perutz’s lab was able to turn out more measurements than ever before. But the measurements, as Perutz later related, did not make any sense. After one of his research assistants completed his postdoc, Perutz looked closer at his results and realized that the new x-ray instruments had not been calibrated correctly.

In 1967, with all the bugs fixed, Perutz and his team put together the first atomic model of hemoglobin, but Perutz’s questions about why the structure changed still were not answered. By 1970, the lab was able to construct an oxygen-free model, allowing Perutz to compare it with the oxygenated model. As Perutz later described “there came this dramatic moment when between them, the models revealed the whole mechanism.” What he was able to see was how a slight movement of the iron atom triggered a change in the whole molecule. Thus, Perutz felt he was able to explain “all the physiological functions of hemoglobin on the basis of its structure.” The results were published in Nature.

Within the field, objections to Perutz’s explanation were numerous and he spent much of the next two decades refuting criticisms and refining his own explanation. At the same time, his celebrity also rose among scientists as he was increasingly invited to give lectures all over Europe and North America. By 1975 Perutz’s fame outside of scientific circles had grown such that Queen Elizabeth II invited him to visit with her at Buckingham Palace. Afterwards, Perutz expressed his regrets to the Queen’s secretary that “she had made me talk away like an excited little boy about my own doings and that I never asked her anything about hers.” Nonetheless, Perutz did hope that the Queen would enjoy his gift, the autobiography of Charlie Chaplin.

Max Perutz with his hemoglobin model. Image credit: BBC.

By 1980 Perutz had begun to reach out to broader audiences more intentionally. Shortly after retiring from the chair of the Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Perutz wrote a memoir of his time there. This, in turn, inspired him to compile an account of his experiences during World War II and submit it to the New Yorker. Penned in 1980 but not published until 1985, “Enemy Alien” helped bring Perutz greater levels of fame, as he received more letters after its publication than he did congratulations for his Nobel Prize.

An Italian pharmaceutical company also approached Perutz in 1980 to give a lecture on the social implications of molecular biology. According to a 2001 interview, Perutz told the company that “molecular biology has no social implications,” but that he could talk about “science as a whole.” This spurred him to take more of an interest in broader scientific questions, ultimately leading him to adopt controversial stances combatting criticism of the Green Revolution, DDT use and nuclear power, among other issues in the headlines. It also evolved into an interest in philosophy – Karl Popper’s Open Society and its Enemies proved particularly impactful. By 1989, Perutz expanded his popular lectures into a book of essays, Is Science Necessary? which included writings that he had also done for the New York Review of Books as well as “Enemy Alien.”

While continuing to write for the New York Review of Books up to the end of his life, Perutz also pursued new research on proteins and hemoglobin, taking a particular interest in neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s. In 2001, right before he passed away, Perutz was still at the lab seven to eight hours a day (including lunch and tea), preparing a publication for the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on the common structure of insoluble protein deposits in neurodegenerative diseases. He passed away at the age of 87, unable to reconcile his initial structure with x-ray diffraction photos which showed contradicting features that Perutz concluded arose from three different structures. The results were published in 2002, after Perutz had died, in two separate articles.