Being an historian by disposition has its own rewards. I relate to the chronicling monks of the Middle Ages and their eagerness to record things. On a much smaller scale, I try to keep track of what has passed in my own small life. As we all know, most days consist of a stunning sameness, particularly if you work 9-2-5. Although your soul is evolving, capitalism’s cookie-cutter ensures a kind of ennui that vacation time, and travel in particular, breaks. Travel is expensive, however. A luxury item. It’s also an education. My wife and I began our life together overseas, living three years in Scotland. We traveled as much as grad students could afford. Gainfully employed in the United States, we made regular summer trips to Idaho, and often shorter trips closer to home in Wisconsin.

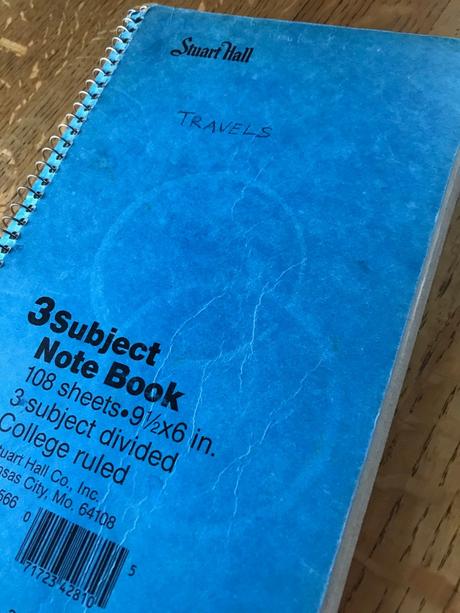

We repurposed an old, spiral bound, three-subject notebook to record our adventures. It spanned twenty-two years. When we moved to our house in 2018, this notebook was lost. (A similar thing happened with an Historic Scotland booklet where we’d inscribed all the dates of properties visited. It vanished somewhere in central Illinois in 1992.) Recently, looking for an empty three-ring binder for my wife to use, I unexpectedly came across our old three-subject notebook. The relief—maybe even ecstasy—it released was something only an historian could appreciate. Here were the dates, times, and places that I thought had been lost from my life. In that morass of years after Nashotah House my mind had gone into a kind of twilight of half-remembered forays to bring light to this harsh 9-2-5 world. I carried the notebook around with me for days, not wanting to lose sight of it.

Those of us who write need to record things. I’ve never been able to afford to be a world traveler. The company’s dime sent me to the United Kingdom a few times, but overseas after Scotland has been more a reverie than a reality. But now, at least, I could remember our domestic trips. The notebook included ventures I’d forgotten. You see, when you get back from a trip you have to begin the 9-2-5 the very next day, particularly if your company isn’t fond of holidays. (This explains why I write so much about them.) Pleasant memories get lost in the mundane cookie-cutter problems of everyday life. And yet I could now face them with that rare joy known to historians. I had a notebook next to me, ready for transcribing. It was going to be a good day.