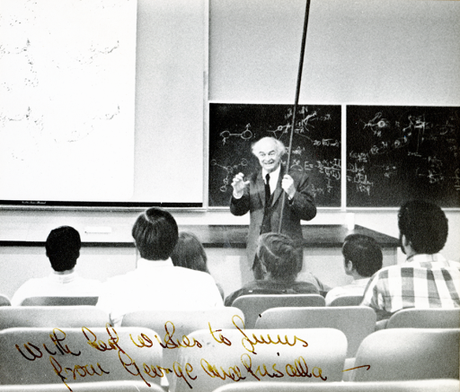

Pauling in lecture at Stanford University, 1969. Photo by George Feigen.

[Looking back on Pauling’s tenure at Stanford University. This is part 4 of 7.]

While at Stanford, Pauling actively sought to make the best use that he could of the laboratory and computing equipment available on the campus. In June 1970, about a year after his arrival, Pauling wrote to Paul John Flory, then the chair of the chemistry department, inquiring about the possibility of his taking charge of the department’s x-ray facilities. The supervisory position had been recently vacated and Pauling suggested that he could run the facilities until the department had found someone more permanent in two or three years.

In presenting this unusual offer, Pauling referred to his need to continue work that he had initiated at UC-San Diego with Art Robinson and Ian Keaveny on the structures of inorganic compounds including delta iron (III) oxyhydroxide and tri-cadmium diarsenide. Having routine access to x-ray equipment, Pauling pointed out, would greatly assist with this ambition.

Besides working out the structures of inorganic compounds, Pauling also sought to develop a new technique to measure atomic distances. To do so, Pauling wanted to attach a computer to an x-ray diffraction apparatus which would convert x-ray diffraction intensity functions into radial distribution functions. In compounds containing two metal atoms, this conversion would serve to determine the distance between the pair. What’s more, the addition of a computer would greatly speed up the process by which this determination could be made — Pauling suggested that results would be available within a few minutes.

ACME designer Gio Wiederhold and technician Voy Wiederhold. Image credit: Stanford Medical School.

Indeed, the advanced computing infrastructure then available at Stanford was very enticing for Pauling and he did what he could to take advantage. Perhaps most importantly, in August 1970 Pauling requested access to ACME, an IBM computing network available to university researchers through Stanford’s Medical School. Usage of ACME was restricted and Pauling needed to submit formal letters to the ACME Subcommittee on User Charges to gain access.

Once he had been approved, Pauling was obligated to pay usage fees through an account that was set up for him and that contained artificially limited funds. At the start, Pauling’s research group would be allocated $200 per month for “pageminutes,” which cost 1 cent, and $100 per month for disk storage, which cost 10 cents per block per month. The amounts allocated to this account were not always enough to cover everything that Pauling wanted to do.

Pauling’s primary interest in ACME was in its use as a tool to analyze the urine of persons suffering from schizophrenia and other mental diseases. In addition to other types of assessments, Pauling’s laboratory carried out chromatographic analyses looking at about 200 different substances in the urine both before and after a given individual had been placed on a special diet and vitamin regimen. As Pauling told Trammell Lonas, who helped to coordinate Pauling’s use of ACME, “The analysis of these data in a reliable way can be made only with use of a computer.” As such, it was critically important that Pauling have access to ACME.

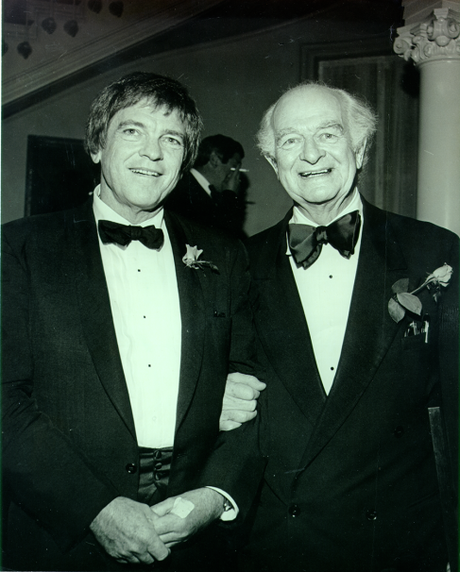

Linus Pauling Jr. with his father at an event in New York, 1971.

Maintaining a well-staffed laboratory was also crucial to moving the schizophrenia research forward. Linus Pauling Jr. – the eldest of the Pauling children and a psychologist who lived in Honolulu – even joined the laboratory as a part-time assistant for a short period beginning in October 1970.

The next month, Pauling offered a Research Fellow position to Paul Cary, who was on leave from the Rockefeller University. Pauling specifically wanted Cary to run the chromatography tests central to the laboratory’s analysis of the urine of schizophrenia patients.

Cary had earlier reached out to Art Robinson, asking him to provide a reference letter as he looked for positions while on leave. Learning this, Pauling decided that it would make sense for Cary to come work for him instead. In his offer, Pauling suggested that “It seems to me that the work has come to a very exciting stage, after a long period of difficulty in getting problems ironed out.” Cary promptly accepted the position.

In October 1973, as part of his laboratory’s development of urine analysis techniques, Pauling also requested the grade point averages of 180 students who were participating as research subjects. In so doing, Pauling explained that “One question that is of interest to us is whether there is a difference in composition of the urine for students with different academic accomplishments.”

As it happened, Pauling was particularly interested in testing A. L. Kubala and M. M. Katz’s results from a 1960 study that showed an improvement in students’ grades after drinking orange juice for several months. Walter J. Findeisen, the recorder at Stanford’s Office of the Registrar, told Pauling that he was not allowed provide GPAs, but that he could could make use of letter grade indicators, such as A, B, C, etc. This is the route that Pauling ultimately decided to take.

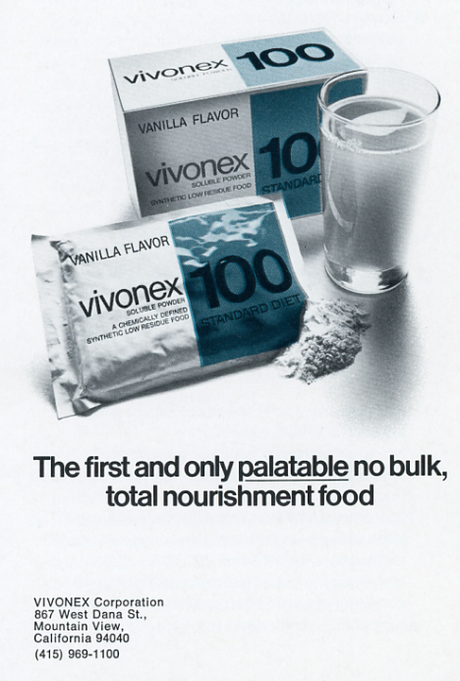

During his time in Palo Alto, Pauling’s nutrition research often took him beyond Stanford’s campus. In the spring of 1970, Pauling became a consultant for Vivonex, a company that produced a nutritional replacement for use by people who were unable to consume food orally and digest it themselves. According to a 1969 pamphlet that Pauling saved, people had lived off of Vivonex for three years straight, all the time relying on the product as their sole source of nutrition. The company also claimed that the product would help to move people towards their “ideal weight.” While Pauling was not offered a fee for his consultancy work, he did receive 500 shares of stock.

Not content to simply act as a consultant, Pauling began taking Vivonex himself, as did Ava Helen Pauling and Art Robinson. In fact, the three lived off of Vivonex as their sole sustenance for three two-week periods. After taking it for a few months however, the three began experiencing headaches and lethargy to degrees that exceeded what they had previously experienced. These symptoms prompted Pauling to ask for a complete list of ingredients, including the quantity of each, and to lessen the intensity of his self-experimentation.

In February 1971, Morton-Norwich Products, Inc. purchased Vivonex, and Pauling was eventually compelled to sell his shares for $18.91 each. Though his more rigorous personal trials with the product did not pan out, Pauling had a good experience with Vivonex overall and he continued to recommend it as time moved forward. In one instance, Pauling’s friend and colleague John F. Catchpool asked him for his thoughts on the nutritional replacement Ensure. Pauling replied that, compared with Vivonex, Ensure was somewhat inferior because it was “essentially a milkshake with added vitamins” and it contained molecules like caseinate that required digestion.

Towards the end of his life, in 1993, Pauling came into contact with Vivonex once more, this time during a stay at the hospital. Though in ill health, Pauling still had energy enough to write to John E. Pepper, the president of Proctor and Gamble, which by then was manufacturing Vivonex. In his letter, Pauling complained of the product’s evolution, noting that it’s now “unpleasant taste” made it impossible to consume. Pauling further informed Pepper that he would no longer recommend Vivonex to others. While Pepper did not respond to Pauling’s complaint, another representative did, telling Pauling that the bad taste was likely due to improper preparation.

Advertisements