[Part 6 of 7 in our series reviewing Linus Pauling’s years on faculty at Stanford University.]

It should come as no surprise that, while at Stanford, Linus Pauling kept a close watch on political activism, both on and around campus. While much of the material that Pauling saved would suggest that he was mostly an observer, a look through the Stanford Daily archives shows that, in fact, he continued to speak on topics related to peace and non-violent protest.

During the years of Pauling’s association with Stanford, both faculty and students alike were involved in demonstrations related to the Vietnam War, which expanded into Cambodia in early 1970, Pauling’s first academic year in Palo Alto. Pauling collected a number of newspaper clippings documenting the protests and occupations that arose that spring in response. Pauling also retained a copy of a letter that Stanford President Kenneth S. Pitzer had sent to President Richard Nixon in which he asked Nixon not to further extend the United States military’s presence in Southeast Asia, arguing that it would only serve to further polarize the citizens from their government.

Around this time, Pauling also received a letter from a group called The Vigilantes, who wrote

We are coming to Stanford to show you our form of demonstration and violence. The first one to get the bullet between the eyes will be you… We know all about you from San Diego… Your days are numbered… we’ll get you.

Though unsettling, this was far from the first time that Pauling had received a death threat. It is unclear who the group exactly was or why they had decided to target Pauling. Fortunately, nothing more came of their threat.

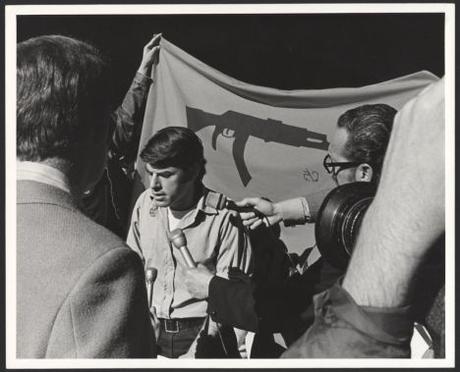

H. Bruce Franklin being interviewed at a press conference, January 1971. Credit: Stanford University Libraries.

It appears that Pauling kept out of much of the direct action, but remained a close observer of those who did participate in demonstrations and how they were treated. One key incident in particular involved a tenured English professor, H. Bruce Franklin, who had been involved in several demonstrations protesting the U. S. military’s actions in Southeast Asia. Pauling collected and saved numerous press releases, newspaper articles, and other documents related to Franklin.

Franklin appears to have first come to Pauling’s attention in early January 1971. At that time, a group of faculty and students had disrupted a speech given at the Hoover Institute by Henry Cabot Lodge, the U.S. Special Envoy to the Vatican. Previously, Lodge had served as ambassador to Vietnam, having been appointed by President Kennedy in 1963. In this capacity, Lodge was involved in the development of both diplomatic and war strategies relating to the Vietnam up through the late 1960s.

After being interrupted during his speech, Lodge moved to a smaller room to continue his talk, commenting that those who shouted over him were “afraid of the truth.” Bruce Franklin was among those subsequently charged by Stanford’s administration for interfering with the event.

In explaining his actions to Richard W. Lyman, by then the Stanford president, Franklin argued that his own “heckling” was not in any way a punishable offense. Lyman disagreed with Franklin’s use of the term “heckling,” and specified that he had been charged with “deliberately contributing to the disturbance which forced the cancellation of the speech.” Lyman continued,

the gravity of the charge cannot be lessened by giving it an amusing-sounding name, for it is an offense that strikes at the University’s obligation to maintain itself as an open forum.

The Stanford president believed that Franklin’s offense was severe enough as to merit suspension without pay for the academic quarter following the resolution of the case. John Keilch, a 24-year-old University Library staff member who was alleged to have also participated in the demonstration, faced a similar suspension. Six students were likewise punished.

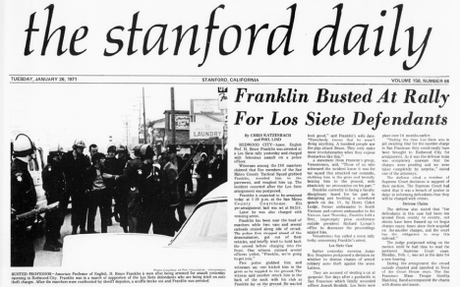

Franklin continued to speak out in the midst of all this. At the end of January, he took part in a demonstration with about 200 others in support of Los Siete — six Latino youths who had been charged with armed robbery and car theft. At the event, demonstrators clashed with police and Franklin was charged with felonious assault for elbowing a police officer in the ribs while the officer pushed Franklin in the back with a baton.

According to the Stanford Daily, Los Siete had previously been acquitted of murdering a police officer, and the new charges of theft had been brought forward following their acquittal. The paper also reported that five police officers had grabbed Franklin, kicking him in the groin and striking him with clubs.

A different newspaper article that was retained by Pauling was far less sympathetic towards Franklin. This piece, which also centered on the Los Siete demonstration, described Franklin as a “proclaimed Maoist” and a member of the “militant” Venceremos, and then printed his home address. Pauling’s reactions to the article are delineated in red ink. He clearly disagreed with the charges brought against Franklin, writing in the margins

Provocation? Marchers had permit for sidewalk. Arrested at RR crossing where sidewalk is not well demarcated from street. Police cars + other cars blocked intersection.

Pauling also drew quotes from the article in support of his position:

“Line of marchers was impeded + some spilled into roadway.” “Franklin elbowed a policeman in the ribs.”

At the end of his notes, Pauling simply wrote, “!FELONIOUS ASSAULT!”

None of this seemed to slow Franklin down. According to a chronology of events created by those supporting his activism, he was also involved in a rally in early February. At this gathering of roughly 750 people, Franklin advocated “shutting down the most obvious machinery of war” on campus, the Stanford Computation Center. In due course, some 150 people – Franklin not included – occupied the center for three hours until it was cleared out by the police.

A second rally of roughly 350 people followed immediately afterwards. Franklin again spoke, telling those in the crowd to return home to form smaller groups and to plan actions that would avoid the attention of the police. The chronology states that, later, “beatings of both conservative and radical students occur, and a high school student is shot in the thigh.”

President Lyman blamed the violence on Franklin, declaring that he “threatens harm to himself and others.” In a Statement of Charges against Franklin, which described the rally in a very different light than the chronology, Lyman wrote,

During the course of the rally, Professor Franklin intentionally urged and incited students and other persons present to engage in conduct calculated to disrupt University functions and business, and which threatened injury to individuals and property. Shortly thereafter, students and other persons were assaulted by persons present at the rally, and later that evening other acts of violence occurred.

In addition to documenting Franklin’s history as they had viewed it, the authors of the chronology created a petition. The intent of this document was that it be presented to Stanford’s Advisory Board, arguing in favor of Franklin’s activities and right to free speech. Linus Pauling’s signature was among those included on this petition.

Advertisements