[An examination of Linus Pauling’s year as president of the American Chemical Society. This is part 2 of 4.]

Having weathered the Henry Wallace controversy, Pauling entered into his presidential year as head of the American Chemical Society, and was immediately apprised of the need to address a significant problem. Namely, by the time he took office in 1949, the ACS had grown too large to function well from a financial standpoint. As a result, the society was constantly plagued by fiscal deficits on the order of several thousands of dollars, and was making budgetary adjustments left and right but still not breaking even.

One of Pauling’s first obligations as ACS chief was to publish a President’s Message in the January issue of Chemical and Engineering News, one of the society’s major publications. In his piece, titled “Our Job Ahead,” Pauling directly addressed the society’s financial difficulties, saying that he was sure the budget issues could be alleviated in a way that would support the society’s cost of operations and the publication of its journals. Pauling also wisely sought to address

…a related problem, the discrepancy between the remuneration of members and the rising costs of living, and to help generally in improving the economic and professional status of chemists and chemical engineers.

From there, Pauling warned his membership against any failure to use science for good, emphasizing the society’s responsibility to “…foster increased understanding and friendship among scientists of different nations” and reiterating the need to create a National Science Foundation. (As the year moved forward, Pauling addressed the issue of a National Science Foundation in several speeches to various ACS meetings, reiterating his support for the program, which had been proposed in the political arena but had not yet taken off.)

The feedback to Pauling’s column was generally positive, with many chemists taking especial heart in learning of Pauling’s concern for their financial well-being.

In mid-January, Pauling began to promote another idea that he supported: the World Calendar. The World Calendar was a proposition that would regularize the lengths of months and theoretically be adopted by every country in the world. In Pauling’s view, moving in this direction would rectify the “inconvenience” caused by the current calendar systems in use, and would make “every year the same.” “The advantages,” as Pauling put it, “are similar to those of an internationally accepted system of screw threads.” At the time that Pauling expressed interest in the idea, it had already been endorsed by seventeen nations around the world as well as multiple scientific organizations.

Correspondence exchanged between Pauling and other ACS executives indicates that there was a general willingness to bring up the idea at a meeting of the Board of Directors, and even some enthusiasm for its endorsement. The topic disappears from the record after January however, and obviously never went far in the national or international political spheres.

In February, a mini-scandal of sorts hit the society when a collection of non-members protested the registration fees required of them to attend ACS conferences that they had been officially invited to present at by the organization itself. Pauling had not known that the society charged registration fees to invited non-members, and expressed vehement opposition to the practice when it was brought to his attention. But Pauling was overruled by executive secretary Alden Emery and others, who pointed out that the practice was necessitated by a clause in the society’s constitution which would be difficult to change.

After a little more digging, Emery discovered that although the society as a whole struggled with funding – as did each local section and the society’s various publications as well – all of the complaints regarding non-member registration fees came from the Division of Biological Chemistry. According to Emery, that particular division was, in reality, in “excellent financial condition.”

Pauling and Emery eventually concluded that the division’s real issue was its lack of appeal to its target demographic. Fundamentally, the division was perceived by non-member biochemists to be more chemical than biological in focus, and therefore not an appropriate environment for sharing and publishing work that was more biological in nature.

As they puzzled over their continuing fiscal woes, the Board of Directors discussed the possibility of increasing membership dues in order to better support the society’s many undertakings. This notion was countered by fears that increased fees might create a corresponding drop in membership that would defeat the purpose. In the end however, the fees went up.

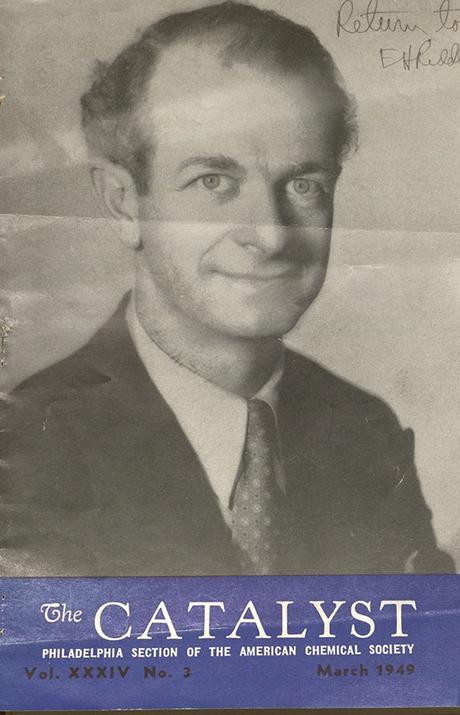

Ralph Spitzer.

Ralph Spitzer.The February 1949 dismissal of Ralph Spitzer from his faculty position in the chemistry department at Oregon State College, which has been written about in detail on this site and elsewhere, hit Pauling hard and brought his liberal political beliefs into the limelight once again. Pauling was a mentor and friend to Spitzer and also an OSC alum; indeed, he had recommended Spitzer for the position at Oregon State.

The grounds for Spitzer’s dismissal were vague, but clearly political in their motivats. Then OSC president August Strand had accused Spitzer of harboring communist sympathies based on his support of Henry Wallace in the presidential election and his advocacy of Trofim Lysenko’s theory of the intergenerational inheritance of acquired characteristics, a genetic theory that had originated in the Soviet Union and that differed from accepted Western theories. (Research in later years would ultimately prove Lysenko’s theory to be incorrect, although it does bear some largely coincidental resemblance to modern epigenetics.) Importantly, rather than an endorsement of the theory, Spitzer’s support was couched mainly in terms of defending the right for Lysenko’s theories to be heard, respected and considered through a scientific lens, and not discounted outright simply because of their Soviet origins.

As his standing at OSC dissolved, Spitzer wrote to Pauling to advise him of the situation and to ask for his help in trying to get his job back. Pauling promptly wrote to Strand to protest the removal of Spitzer on political grounds, which he considered to be an infringement of academic freedom since there had been no complaints of Spitzer’s political leanings affecting his research or teaching.

The year before, Pauling had publicly spoken out against the House Committee on Un-American Activities for not giving scientists the chance to defend themselves against accusations of disloyalty. Now he found himself in the midst of a public feud with August Strand over Spitzer’s dismissal, which culminated in a public rending of Pauling’s previously strong bond with his undergraduate alma mater. Pauling and Spitzer later took part in a forum on the perceived incompatibility between academic freedom and Communism, joining a set of professors from other universities who found themselves in the same boat as Spitzer. Documentary evidence as to how the ACS handled all of this is lacking, but the membership’s broad reaction to Pauling’s support for Henry Wallace leads one to suppose that the society was likely none too pleased about it.