[An analysis of Linus Pauling’s tenure as President of the ACS, published on the fifty-year anniversary of his holding the office. This is part 1 of 4.]

Linus Pauling was elected future president of the American Chemical Society in December 1947. In that capacity, he served as the society’s president-elect for 1948 – during which time he was living in England as a visiting professor at Oxford – and officially took up his post as president in 1949. He formally assumed office on January 1, 1949, with Ernest H. Volwiler serving as the president-elect for the year.

The news of Pauling’s election as ACS president was widely publicized in early 1948, with one short announcement reading:

Chemist’s Chief – Dr. Linus C. Pauling, chairman of the division of chemistry and chemical engineering at the California Institute of Technology, has been elected president of the American Chemical Society. One of the world’s leading theoretical chemists, he was chosen in a national mail ballot of the society’s 55,000 members.

This same account was used in multiple newspapers with only slight variations. Chemical and Engineering News, one of the ACS’s signature publications, released a slightly longer announcement in 1949 describing Pauling’s achievements in the field, including his academic positions past and present, and his laundry list of awards and honorary degrees.

News of his election was initially well-received by scientists both within the society and outside of it, and Pauling received letters of congratulation from many of his new constituents expressing their excitement at being led by a chemist of such high ability and international renown. However, as seemed to always be the case with Linus Pauling, his political stances quickly became a point of contention between himself and others within the ACS.

While many members wrote to Pauling expressing their joy at the election of a political liberal (one correspondent, Bernard L. Oser of Food Research Laboratories, Inc., wrote that “The ACS has done honor unto itself by handing the gavel to a great liberal as well as a great chemist”) a larger and more vocal group of society members quickly withdrew their support. Indeed, Pauling’s liberal politics and anti-war work would keep him under near-constant scrutiny for the duration of his presidential year.

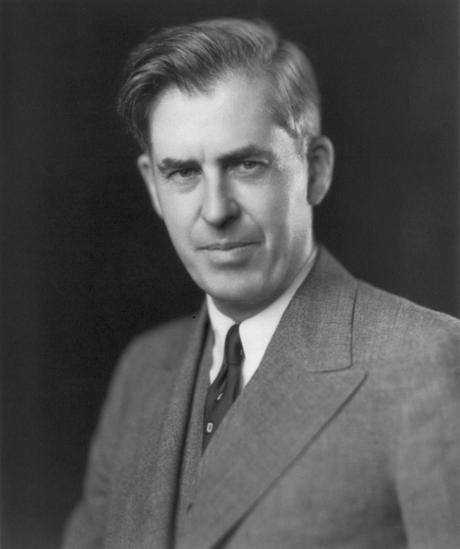

Henry A. Wallace

Henry A. WallaceIn November 1948, near the end of Pauling’s stint as president-elect, the first of the political controversies arose. In this instance, the catalyst was a pamphlet featuring Pauling’s name at the top of a list of sponsors endorsing presidential candidate Henry Wallace. Wallace had served as vice president under Franklin D. Roosevelt and ran in the 1948 election as the Progressive Party nominee.

When he learned of the pamphlet, Henry C. Wing, the chairman of the ACS Board of Directors, wrote a letter to Pauling reprimanding him for publicly supporting Wallace, who had been accused of displaying Communist sympathies. In the letter, Wing suggested that “…your action has impaired the high position of our Society in the eyes of Congress and the nation, as it is impossible for you to separate your actions as an individual from that of the President of the Society.” Wing then warned that “There can be no question concerning the loyalty to the United States of the vast majority of the members of the Society…” and notified Pauling that his behavior would be discussed at the next section meeting.

Other ACS members wrote to the Board expressing similar concerns. One member, R.H Sawyer, summed up the views of others in asserting that, although Pauling’s name on the pamphlet was in no way overtly connected to the ACS (his professional associations were not listed), it still reflected badly on the society to have its members endorsing such politics. Sawyer then theorized that perhaps Pauling’s name had been used without his consent and called upon Pauling to confirm or deny his endorsement of Wallace. “Should [Pauling] fail or refuse to do so,” Sawyer warned, “I call upon the American chemist to repudiate as a political crack-pot the man they have honored as a scientist by election to the office of President Elect of the American Chemical Society.”

A different ACS member, M.L. Crossley, offered a similar complaint, explaining that:

…I shudder to think of what some of the radio commentators may do with the information that the President of the American Chemical Society is a sponsor of the Wallace-Marcantonio brand of politics. I register now and ever the strongest protest against any action by an officer of the American Chemical Society which may be used to convey the impression that I as a scientist and a member of the American Chemical Society subscribe to such a brand of dangerous, fanatical philosophy of government. I am a true American, believing in the principles of the philosophy of our democracy which has made this country the greatest land of freedom and opportunity the world has ever known.

While Sawyer and Crossley wrote to members of the ACS administration, others chose to address Pauling directly. These letters of criticism complained about his political views and expressed surprise that a man as intelligent as himself would be so liberal. The correspondents also requested that he release a statement clarifying his political views, and some even called for his resignation as president-elect.

Dr. Louise Kelly was one such author, lamenting to Pauling that “Having in the past had a high regard for your intellectual ability…” she was appalled to receive the pamphlet and find out that he was a Wallace supporter. Kelly continued,

I can understand why certain types of individuals, whose mental processes (I refuse to employ the word “thinking”) are as confused as those of Mr. Wallace, have been converted into followers of his, but I am at a loss to comprehend your position.

Pauling did not deign to accommodate requests for his resignation or to issue a public statement on his views, but he did reply to the letters that were sent directly to him. Confident as ever, Pauling answered Dr. Kelly’s letter by requesting that she re-evaluate her refusal to use the word “thinking” in conjunction with Wallace supporters, writing “I assume that you consider me to be a reasonably clear-headed fellow.” He finished by assuring her that there was no need to be shocked and appalled – his political leanings had never been a secret, and he promised that “I haven’t changed much in recent years, except that my health is not so good as it once was, my hair is getting thin on top, and my social conscience has grown a great deal.”

Dr. Joel Hildebrand had also written directly to Pauling critiquing his political views, portraying Wallace as an idiot and a wannabe-dictator, and insulting Pauling’s intelligence for supporting him. Although Wallace ultimately accumulated just a small share of the popular vote in the 1948 election, Democrat Harry S. Truman’s victory over Thomas Dewey informed Pauling’s somewhat sarcastic response to Hildebrand. “The presidential election was great fun,” Pauling quipped. “I don’t know when I’ve enjoyed anything more than the upset of the Republicans.” Pauling concluded his letter by casually informing Hildebrand that Ava Helen had broken a bone in her ankle.

Although the ACS was officially a non-political organization, the bulk of its membership seems to have been politically conservative. The response that Pauling received to his endorsement of Henry Wallace is illustrative. In reality, Wallace’s platform was not Communist, but forward-thinking and focused on social justice. Wallace called Truman’s government war-mongering and hypocritical for pushing universal military training and a draft system while veterans returned from war were rendered homeless and unemployed. Wallace also believed that war profiteering on Wall Street was a source of the country’s increasing militarism. Wallace likewise viewed the Marshall Plan as a tool for the U.S. to cement political and economic control of Western Europe; he encouraged aid for Europe but wanted to work through the United Nations to insure that support was provided with “no political strings attached.”

Wallace campaigned for world peace and civil rights for minority communities, and his platform included calls for desegregation and anti-lynching laws, outlawing the poll-tax, and providing federal inspections of polling places to ensure fair voting conditions. He also pushed for a fair employment practices act, desegregation of the government and armed forces, and the withdrawal of federal aid from any institution engaging in discriminatory practices. He advocated for the end of Jim Crow legislation and sought to eliminate discrimination against African Americans, Jews, and “citizens of foreign descent.”

Pauling strongly believed that his actions as an individual remained separate from his role as ACS president so long as he did not leverage his position in order to support his political views. To this end, he made a point of not listing his academic or professional affiliations whenever he allowed his name to be used for political ends. He pointed out that he had never kept his views a secret and that his election had nothing to do with his politics.

In their exchange of letters, R.H. Sawyer retaliated that most of the society members who voted for Pauling would not have done so had they known of his political affiliations. Whether or not Sawyer was right, the Wallace affair was the first taste of a continuing conflict between Pauling and the ACS that would taint his entire presidential year.