[Ed Note: The Pauling Blog becomes a teenager this week! On March 4, 2008 we introduced ourselves to the world with our first post. Thirteen years later, we’re thrilled to be publishing post 5 of 10 in our series on schizophrenia, and post number 810 overall. Our continuing thanks to the many readers who have helped make this such a rewarding experience for the duration.]

As we have seen, Linus Pauling’s work on the use of orthomolecular therapies as a treatment for schizophrenia never attracted anything like widespread acceptance from mainstream psychiatric and psychological professional organizations. But despite this, Pauling’s ideas did attract attention and respect from other corners of the mental health profession, both individuals and groups.

In addition to Abram Hoffer and Humphry Osmond, another early proponent of the orthomolecular approach to schizophrenia was Harry Vanderkamp, who worked for the Veterans Administration Hospital in Battle Creek, Michigan. Notably, in 1966 Vanderkamp published an article in the journal Neuropsychiatry titled, “A Biochemical Abnormality in Schizophrenia involving Ascorbic Acid.” The paper, which Pauling noted and which actually preceded his own first publication on the topic by about two years, echoed the basics of Pauling’s core thesis; that schizophrenia could be successfully treated through megavitamin dosing. In the article, Vanderkamp specifically argued that schizophrenia patients could “metabolize ten times as much [vitamin C]” as those without schizophrenia and that, as such, one might reasonably draw a connection between schizophrenia diagnosis and low levels of vitamin C.

The ideas of Vanderkamp and others informed Pauling’s first formal paper on the subject, “Orthomolecular Psychiatry: Varying the Concentrations of Substances Normally Present in the Human Body May Control Mental Disease.” The article appeared in the April 1968 issue of Science, and attracted a great deal of interest. One particular outcome was a series of invitations to speak on the topic at Tulane University, which invited Pauling to address the school’s entire medical school in May 1970 and again in March 1971. Pauling was chosen for this honor by unanimous decision of the school’s faculty and students, and in both instances the title of his lecture was simply, “Orthomolecular Medicine.” The same was true for a spring 1971 lecture at the University of New Brunswick, as well as four other major talks delivered between 1968-1972.

Pauling also found traction with the American Schizophrenia Foundation following the 1968 publication. Shortly after it appeared, the organization (which later changed its name to the American Schizophrenia Association), offered Pauling space in its newsletter to expand upon his academic work and defend his ideas as necessary. Pauling took advantage of this offer and in the October 1968 issue wrote that megadosing was safe and effective, and that any “psychiatrist who refused to try the methods of orthomolecular psychiatry, in addition to the usual methods, is failing in his duty as a physician.”

Two-and-a-half years later, despite the negative press that Pauling was receiving, the ASA granted Pauling an undisclosed monetary award and provided an additional $1,000 to Stanford University – where Pauling was working at the time – to support continued research on the orthomolecular approach to schizophrenia. Later that same month, the association’s journal, which had been titled Schizophrenia, changed its name to the Journal of Orthomolecular Medicine. At the time of the change, the journal was being edited by Abram Hoffer, who wrote to Pauling that the new name “more accurately reflects the spectrum of [the publication’s] concern.”

Other academic support for Pauling came from the Journal of Autism and Childhood Schizophrenia. Founded in 1971, the journal’s first editor was Leo Kanner, a leading figure in child psychiatry. From the start, Kanner wanted Pauling to serve on the journal’s board as a contributing editor. Pauling accepted this offer and remained a member of the board until 1979, when the mission of the publication changed. But during those years of association, Kanner stressed that Pauling’s role as a contributing editor boosted the publication’s name recognition and, importantly, its credibility. Pauling seemed to enjoy the connection as well, joking at one point that, “Years ago I was a member of the Editorial Board of J.A.C.S. It was, however, the Journal of the American Chemical Society.”

In 1973, when negative press surrounding megadosing crested in the wake of the American Psychiatric Association’s damning task force report, a second round of support for Pauling and orthomolecular medicine emerged in response. In private correspondence, colleagues like J.B. Drori, Chairman of the Committee of Education at John Muir Memorial Hospital, wrote that despite the fact that Pauling’s ideas “have not been widely accepted,” they still “seem to make a lot of sense to me.” Likewise Dr. C. David Geer, chair of the New Jersey Schizophrenia Foundation, who publicly lauded Pauling’s work, noting to a reporter that his own research on megadosing had come to pass as a result of the momentum that Pauling had brought to the field.

And Pauling naturally retained the support of his friends. High among them was Humphry Osmond, who often rallied around Pauling and offered public praise. So too Abram Hoffer who, in a piece detailing historical advances in schizophrenia treatment, wrote of the late 1960s that “Dr. Linus Pauling’s concept of orthomolecular psychiatry seemed most appropriate at the time and still does.” For Hoffer, Pauling was clearly “a major historical root” for the field.

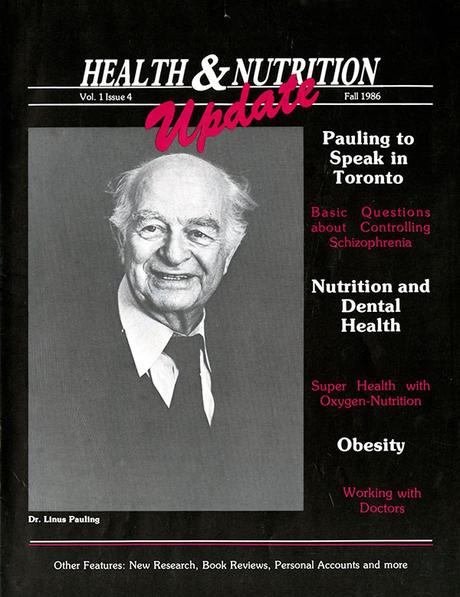

Hoffer and Pauling’s professional connection eventually evolved into a tight friendship. In 1986, for example, Hoffer was invited to celebrate the launch of an endowed orthomolecular chair at Ben Gurion University in Israel. In agreeing to do so, Hoffer further suggested that Pauling’s presence would be a “a major attraction” and “a marvelous opportunity to promote [his] books.” (and thus the benefits of orthomolecular medicine). Hoffer, who often referred to Pauling simply as “Linus” in their correspondence, ultimately covered the full cost of Pauling’s trip to Israel.

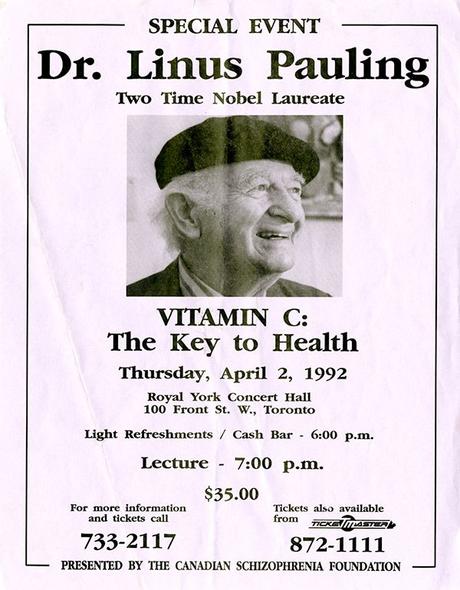

On another occasion, Hoffer arranged for a “Linus Pauling Reception Dinner,” which was held to raise funds for the Canadian Schizophrenia Foundation, with Pauling set to receive half of the proceeds. At a rate of $25 per person and $45 per couple, Pauling’s share of the gate was $4,275.46. This model of generating support and raising money for orthomolecular causes was so successful that the foundation set up another lecture series for Pauling in 1992. Even though Pauling announced that he had cancer in February of that year, he was determined to attend the event to support Hoffer and to help raise funds for an organization that he believed in.