[Part 3 of 10]

“I feel, accordingly, that it is the duty of every psychiatrist to add megavitamin therapy, orthomolecular methods, to his armamentarium, and to make use of these vitamins, to try them out in proper amounts, not just by doubling the recommended daily allowance, but in the proper amounts as discussed by Dr. Hoffer and others here as having been found to be effective for many patients.”

-Linus Pauling, speech to the American Schizophrenia Association, July 1971

Upon learning about the potential that vitamin megadosing might have for improving the lives of people suffering from schizophrenia, Linus Pauling quickly began thinking about a new research program. This process was only accelerated by his interactions with Irwin Stone, who introduced vitamin C as a potential tool for attacking mental disease, among other health maladies. One piece that Pauling still needed however, was a more complete understanding of how best to run the types of experimental trials that he had in mind. To bridge this gap, Pauling once again turned to the literature, reading everything that he could find that was even remotely related to orthomolecular protocols.

One interesting resource that Pauling consulted amidst his information gathering process was the Veteran’s Administration. Specifically, in June 1967 Pauling asked the VA’s chief of psychobiology research, Arthur Cherkin, to provide a digest of all research that had been done by the federal agency on the correlation between mental disorders with nutrition, protein deficiencies, and vitamin deficiencies. Cherkin was happy to help, supplying Pauling with notes on some 500 different studies that involved these topics.

A few months later, Pauling also reached out to Humphry Osmond to ask if he knew of any “psychiatrists, especially in California, who are sympathetic to the use of nicotinic acid, nicotinamide, and ascorbic acid in the treatment of schizophrenia.” What seems to be clear in these exchanges is that even though Pauling had read reports about the design and effectiveness of other trials, he was still pondering how best to organize his own experimental approach.

By December 1967, Pauling was feeling more ready to begin his research. His careful reading of the literature had convinced him that schizophrenia could be caused by a nutritional imbalance of nutrients, and that orthomolecular therapy could be of great benefit. He also had a good idea about the analytical tool that would drive his experiments.

From the beginning, Pauling worked closely with his University of California – San Diego colleague (and former Caltech student) Art Robinson. Together they collaborated with County University Hospital in San Diego to conduct human trial nutrient tests on patients with schizophrenia. The study initially tested the trial group’s capacity to absorb vitamin C, and was later repeated to analyze absorption of vitamins B3, B6, and B12. Importantly, as he had done in the 1940s, Pauling once again relied upon urinalysis to compile his data. In the County University Hospital trials, subjects’ urine was collected and analyzed both before and after dosing with vitamin C, which was ingested in the form of orange juice.

Art Robinson, 1974.

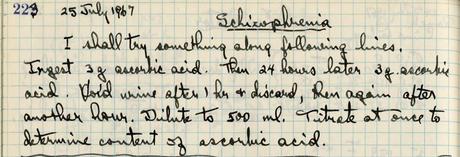

Art Robinson, 1974.Though the urinalysis approach had proven unsuccessful in the 1940s work, Pauling was inspired to try it again as a result of his more contemporary reading. In one particularly relevant research notebook entry, dated July 25, 1967, Pauling analyzed a 1966 paper in which author H. VanderKamp reported on his use of urine sampling to investigate ascorbic acid and thorazine treatments for schizophrenia patients. The idea was clearly enticing for Pauling, who wrote in his journal that day, “Could a urine test be useful in diagnosis?” The answer proved to be yes, and by the time Pauling was running his human subjects trials in San Diego, he had fine tuned his approach. To test the amount of vitamin C present in a urine sample, Pauling and Robinson would use gas chromatography to detect the presence and quantities of aromatic compounds that are created when vitamin C reacts with alcohols.

The initial trials showed promise, with “all patients elevat[ing] to normal levels [of vitamin C] after eight days” of treatment. This finding aligned with Pauling’s hypothesis that vitamin C levels in schizophrenics were too low, and that through supplementation they would be able to reach “normal” levels in a relatively short period of time.

Pauling and Robinson’s first data set was exciting enough that they decided to apply for funding to expand the scale of their project. In mid-1968, the duo submitted a grant proposal titled “Orthomolecular Psychiatry – Diagnosis and Therapy” to the National Institutes of Health, requesting $336,945 (roughly $2.7 million in 2020 dollars) to support work conducted from January 1, 1969 to December 31, 1973.

The proposal outlined a plan that would follow the same general procedure as before, centering around the administration of “oral doses of substances and then to analyze samples of urine” using “chemical, microbiological, spectrophotometric, and gas chromatographic methods.” The substances that Pauling and Robinson planned to test were “ascorbic acid [vitamin C], nicotinamide [B3], pantothenic acid [B5], cyanocobalamin [B12], and pyridoxine [B6].” However, unlike the previous study, this project would also make use of controls – people who did not have schizophrenia – including “nurses, physicians, students, [and] faculty members.”

In justifying the proposal, Pauling admitted to grand ambitions, stating that

We are not attempting to carry out a definitive test of a well-defined hypothesis, but rather to discover something about mental disease. I hope that it will turn out that what we are doing now is analogous to what my coworkers and I did between 1945, when I had an idea about the nature of sickle-cell anemia, and 1949, when Drs. Itano, Singer, and Wells and I published our paper, “Sickle Cell Anemia, a Molecular Disease.”

The study was funded, and also happened to coincide with a period of rapid change for Pauling, whose institutional home shifted from UCSD to Stanford to the Institute for Orthomolecular Medicine (co-founded by Pauling and Robinson) during the lifetime of the grant. Despite all these transitions, Pauling published a number of papers as a result of the grant, all of which emphasized a positive relationship between vitamin megadosing and improved health for schizophrenia patients. As its profile rose, the work also began to attract interest from additional funding sources including, as communicated in a 1978 letter from Art Robinson, “the Multiple Sclerosis Society, the Educational Foundation of America, the National Cancer Institute, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.”

As the program moved forward, Pauling continued to devote time and energy to perfecting experimental design and minimizing side effects for trial participants. In his correspondence with Humphry Osmond for example, regular attention is given to defining proper dosages and best practices for maximum absorption. Taking supplements with Coca-Cola was, for instance, ill-advised, and so too with caffeinated coffee. Concerns were also raised about the sugar content in fruit juices, and eventually pure glucose was used to sweeten the vitamin C trial drinks. Likewise, milk was not recommended for any person of African or Asian descent, and at least two or three grams of bran were to be given to all patients per day “to help avoid the use of laxatives” often needed by those taking high doses of antipsychotic drugs.

One major trial that involved Pauling and Robinson as collaborators was titled “Urine Biochemistry in Schizophrenia and the Effects of Vitamin Loading,” and was carried out at the Agnews state mental hospital in Santa Clara, California. Pauling and Robinson were primarily asked to take charge of analyzing urine samples collected from the 200 schizophrenic patients recruited into the study, but the importance of Pauling’s past work clearly permeated the new trial. In the study’s introduction, lead researcher Maurice Rappaport pointed out that

Pauling, on the basis of previous research, has reached the conclusion that there are differences in the metabolism of ascorbic acid, nicotinic acid and pyridoxine between those who are in good mental health and those who are in poor mental health. Specifically he reports that among the mentally ill as compared to the mentally well, ‘there is a much larger group of people with unusually high requirements for one or another of these three vitamins.’

The sum result was

a theory of mental ill health based upon the fact that a man’s normal diet does not always supply the amount of essential nutrilites necessary to establish an optimal molecular environment for his mind. Further, [Pauling] has suggested that there are biochemical variations in some men which cause their requirements for essential nutrilites to be so unusual that the failure of their diet to satisfy these requirements results in mental illness.

Clearly Pauling’s work had made a significant impact in a short period of time. But, as we shall see, signs of trouble were soon to appear.