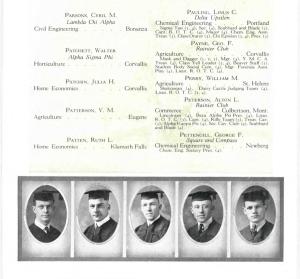

Illustration for the Forensics Club section of the 1923 OAC Beaver Yearbook.

[Continuing our examination of the culture of oratory at Oregon Agricultural College during Pauling’s undergraduate years. Part 2 of 2]

This coming Saturday, Oregon State University will host its 146th commencement exercises. As the campus buzzes with students finishing their finals and seniors looking forward to the pomp and circumstance that awaits, we turn our attention back to Linus Pauling, and a noteworthy speech that he gave just five days before he completed his undergraduate studies in Corvallis.

“It is not given to every man to be unusually successful, to be extraordinarily talented, or to be exceptionally gifted to render services to the world. We can do no more than we are able, but by doing as much as we are able, by doing our best, we shall be accomplishing our task, and repaying our debt. For our college has given us something which will allow us to do more than we otherwise could; and we must do more than we otherwise would.”

-Linus Pauling, Senior Class Oration, May 31, 1922

As we learned in our previous post on oratory at Oregon Agricultural College (OAC), forensics was an art form held in high esteem by the culture of the early in the twentieth century. The presence of a reputable orator at an institution symbolized a high level of cultural competence. For this reason, most colleges and universities of the time prioritized this activity and provided their students with the necessary tools to become competent public speakers. Consequently, being chosen to deliver a speech at any given event was considered to be an honor, and especially so at a high profile event.

During Linus Pauling’s years at OAC his close and lifelong friend, Paul Emmett, was heavily involved in the school’s forensics club, a likely reason why Pauling chose to join during his junior year. That year, Pauling entered competitive oratory for the first time and was chosen to represent his class in the inter-class competition, where he finished as a runner up for the title of college orator.

Although he came in second, Pauling’s achievement was impressive for a beginner, as oratory’s popularity and competitive nature was rapidly increasing at the time. Indeed, the year before Pauling joined the forensics club, the college had established a speech department and went from training only a handful of public speakers to a group of fifty to seventy-five orators per year, participating in ten annual competitions.

After 1921 Pauling no longer shows up in OAC’s forensics club records, but his participation in oratory at the school surely continued. Most notably, Pauling was chosen to deliver the senior class oration, an indication that his status as a prominent and respected speaker remained intact.

“Seniors Attend Farewell Convo,” OAC Barometer, June 2, 1922.

Delivered on May 31, 1922, six days before commencement, the speech that Pauling prepared urged his fellow classmates to use the knowledge that they had gained at OAC to attack the problems facing society. Where his junior year oration, titled “Children of the Dawn,” felt simplistic and perhaps overly optimistic, Pauling’s senior class talk was characterized by its emphasis on personal responsibility and the “problems of the state,” a term that referred to the social and political issues that had emerged from the destruction of World War I. “Our lives are to stand as testimonials to the efficacy of the work that our college is doing,” Pauling said. “Education, true education, such as our own college gives us, is preparation both for a life of appreciation of the world and for a life of service to the world”

Another point that Pauling stressed in his address to the senior class was that of “repaying OAC.” It this, one might surmise that Pauling was speaking both of value gained from OAC and from the system of higher education as a whole. It is important to point out that the systematic killing of troops that characterized World War I had fractured the public’s feelings about research in the sciences. As noted by Pauling biographer Thomas Hager, a common argument at the time was that science was the cause of the war’s deadly nature. Out of this experience, numerous questions lingered. Should education work to propel science and technology? Was further development of science potentially harmful to society?

In this context, Pauling’s calls for individual responsibility and service to society can be viewed as a reaction against the negative connotations then being ascribed to various educational pursuits. And so it was that Pauling took pains to point out that OAC, Oregon’s land grant institution, “has contributed in a wonderful way to solving the multitude of problems arising in the state.” Likewise, near the conclusion of his talk:

This, then, is the way we can repay OAC – by service. Our college is founded on the idea of service, and we, its students, are the representatives of the college. It is upon us that the duty falls of carrying out that basic idea. We are going into the world inspired with the resolution of service, eager to show our love for our college and our appreciation of her work by being of service to our fellow men.

In emphasizing the idea that knowledge acquired at OAC was a tool that could be used for the benefit of society, Pauling’s speech makes the argument that the development of knowledge in any field cannot be intrinsically evil. Rather, each educated individual has the opportunity to render their knowledge in either beneficial or harmful ways to the greater population and, in Pauling’s view, bears a responsibility to use their talents for the improvement of society.

Pauling’s senior class photo (lower left) and inscription (upper right), 1923 OAC Beaver Yearbook.

The contents of his two major orations at OAC suggest that, even at the earliest stages of his career, Linus Pauling had developed a sense of the values that he intended to promote. For one, he was sure that the pure and applied sciences were important to improving the quality of life of all people. Pauling was also conscious of science’s potential for harm however, and as an undergraduate he began to promote the idea that the privileges of education carry with them with a responsibility to contribute to the greater good.

As Pauling’s career advanced, so too did his positive view of the future of science. After winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1963, Pauling took the opportunity, during his Nobel address, to once again exclaim that those who have received the opportunity to study the physical world should devote themselves to becoming responsible citizen-scientists. An extension of ideas first expressed in the OAC Men’s Gymnasium in 1922, Pauling pointed out that scientists who were conscious of the possibilities that their knowledge opened up were morally obligated to share their knowledge of the physical world in ways that benefited humankind.