SATC cadets being addressed by OAC President William Jasper Kerr, October 1, 1918.

[Examining Linus Pauling’s sophomore year at Oregon Agricultural College, the 1918-19 academic year. This is part 2 of 3.]

While World War I began in the summer of 1914, it was not until April 1917 that the United States entered the field of battle. During this time, Oregon Agricultural College became a significant site for military training and was particularly well-known for producing young enrolled officers. In 1918, a Student Army Training Corps unit was established on campus, and the early period of Linus Pauling’s sophomore year at OAC was dominated by SATC influence.

The SATC was created to allow young men to enroll in the military while still furthering their technical education. From the outset of hostilities, the War Department established as a high priority the need to maintain standards of higher education for the nation’s youth and, in particular, to build practical skills for those who would eventually serve.

While the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) had been established a few years prior, during the war the SATC effectively replaced the roles and responsibilities that the ROTC had been meant to build and organize. Nearly half of all male students at OAC were enrolled in the SATC during the school year, and Pauling was among them. Following the conclusion of the war, Pauling remained active in the ROTC as well. Indeed, by the time that he graduated from OAC, Pauling had been promoted to the rank of Cadet Corporal within local Company H.

Benton County (Oregon) War Bonds poster, 1918.

The Great War made a tremendous impact on students at OAC and with the establishment of the Corvallis SATC unit the college became a West Coast epicenter for military training. The urgency of a war-time curriculum was partly enabled by a shift away from semesters in favor of an academic quarter system, which allowed for three-month training periods that dovetailed more readily with the military’s needs.

Following American entry into hostilities, OAC also began to heavily promote student enrollment in classes that would support the war effort. Many courses at OAC were likewise adapted to fit the needs of the moment. This shift was most pronounced within the School of Engineering, with courses in mechanical, electrical, experimental, civil, chemical, and mining engineering quickly reimagined to strengthen the student body’s readiness for battle.

For Pauling, who was a chemical engineer, these adjustments manifested in three specific classes that were new to the college’s course offerings: “Explosives” in fall term, “Camp Drainage/Trenches Issues” in winter term, and “Excavation for War Purposes” in the spring. As with all other SATC students on campus, Pauling was also committed to a rigorous training schedule, often devoting multiple hours in a day to military drills. These shifts in obligations did nothing to wither his enthusiasm: throughout the war, Pauling remained a steadfast and enthusiastic supporter of the American effort, and was later described as “100% for it” by his cousin Mervyn Stephenson.

Indeed, during the war years, communities across the United States were enveloped by a wave of nationalistic feeling, and Corvallis was no exception. On October 1, 1918, the community put forth a Pledge of Loyalty with 3,000 male students, between 700-800 female students, and nearly 10,000 Benton Country residents signing on. Uncle Sam was likewise a regular character in the school’s newspaper, The Barometer.

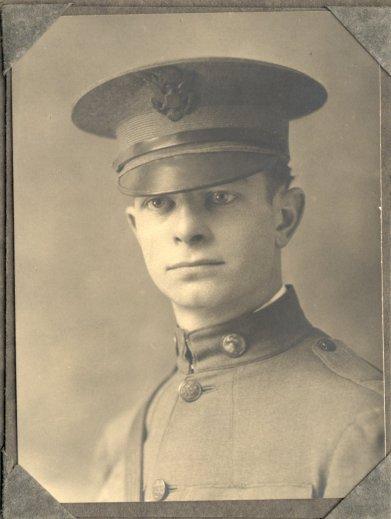

A portrait Pauling in his military dress, 1918.

And while the armistice did not bring with it an immediate dismantling of war-time activities, the thoughts of many began to shift toward ideas on reconstruction in the post-war period. Students throughout campus debated the specifics of how best to proceed through the months and years ahead, with many agreeing on a global industrialized democracy as the ideal for moving forward. In letters to The Barometer, multiple students further commented on the role that higher education would play in this vision for the future. One writer perceptively offered that OAC had become an important breeding ground for future leaders and

will have to broaden out into bigger lines of thinking, for the world is demanding real leaders who are more than technical leaders.

In another demonstration of the lasting effects of the war, the Oregon legislature passed a law in the months following the Armistice that made military training compulsory for high school boys throughout the state. Similar regulations remained in colleges like OAC, where ROTC programs had already been mandatory for male students.

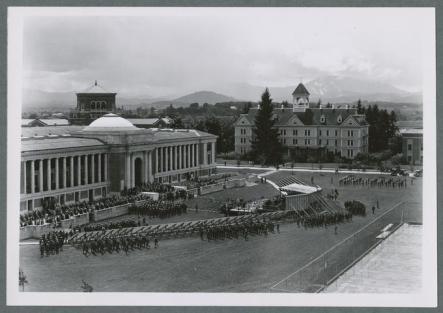

Dedication of the Memorial Union, June 1, 1929

Oregon Agricultural College lost 51 students and staff in battle during World War I. Their collective sacrifice was not forgotten by OAC, an institution that took seriously its long tradition of military service. In 1920, proposals for a student activity center that would “stand as a lasting memorial erected to the honor and memory of the students and alumni who gave their lives in the service of their country” began to circulate on campus. Pledges were solicited not long after and, in 1927, excavation began in the heart of campus. Completed in 1928 and dedicated a year later, the Memorial Union now serves as a warm, welcoming and universally beloved space for OSU students to study, socialize, rest and reflect.