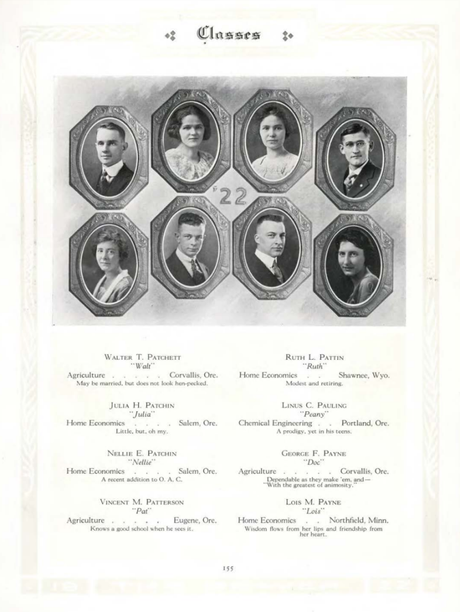

“Peany” Pauling – “a prodigy, yet in his teens.”

“Peany” Pauling – “a prodigy, yet in his teens.”[A look back at Linus Pauling’s undergraduate experience at Oregon Agricultural College one-hundred years ago. This is part 1 of 3.]

The 1920-21 academic year at Oregon Agricultural College (present-day Oregon State University) marked a season of change for Linus Pauling, both academically and personally. The previous year, due to financial constraints, Pauling did not enroll in classes but instead taught introductory chemistry courses at OAC in order to make ends meet. But by the fall of 1920 Pauling was able to resume his studies, having saved up from his teaching and from a summer job working as a paving inspector in southern Oregon. As such, even though it was Pauling’s fourth year at OAC, he recommenced his academic work with junior year standing.

When Pauling moved back to Corvallis in September 1920, he rejoined the Gamma Tau Beta fraternity, one of the smallest Greek houses on campus. Pauling’s involvement in the fraternity had been crucial to his social development, and his year out of school had also provided ample opportunities for personal growth. Partly as a result, when Pauling returned to student life he was no longer so strictly interested in chemistry, but instead began to dabble in a number of additional pursuits, excelling at most.

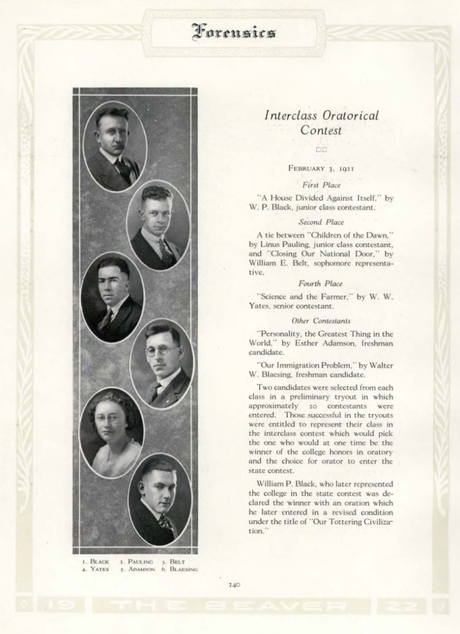

One of the most significant diversions from chemistry that Pauling began to pursue was competitive public speaking. When he first came to OAC, Pauling was, by his own account, a shy individual lacking in self-confidence. However, as time went forward (and perhaps spurred by his experiences as a teacher) Pauling developed a degree of confidence and interest in oratory that he pursued for the final two years of his OAC career. And so it was that Pauling jumped at the opportunity to participate in the school’s annual campus-wide competition, even seeking out the help of an English professor (and former minister) to assist with his diction and delivery.

Though the all-campus contest was open to anyone, each class was ultimately required to nominate two participants to serve as its representative. Following a rigorous vetting process, Pauling was selected as one of the two junior class nominees. His speech, titled “Children of the Dawn,” was a plea for scientific rationalism and offered firm support for Darwin’s thinking on evolution. Though ably delivered, the content of the lecture may have been too progressive for the competition’s judges, and Pauling ultimately lost out on first place to his fellow junior class nominee, William P. Black, whose speech was decidedly less controversial. Black, who went on to win second place in the statewide speech contest, delivered a talk titled “House Divided Against Itself.” Pauling tied as runner up with the sophomore candidate, who spoke out against stifling immigration in his lecture, “Closing our National Door.”

Despite coming up short in the final judging, the OAC contest aided Pauling in his maturation as a person and aspiring academic. Mostly due to his excellence in the classroom, but also prompted by his strong performance in the oratory event, Pauling was invited by members of the OAC faculty to apply for a Rhodes Scholarship, an application that ultimately fell short.

Pauling was naturally disappointed by the decision of the Rhodes committee, but he was also able to see a silver lining. As he recalled years later, Oxford’s chemistry department – where he would have studied had he been awarded the scholarship – was stuck in the past. In Pauling’s view, the department’s faculty were not interested in some of the new innovations emerging within the discipline, and had he attended Oxford at an impressionable age, he may well have been steered down a less prosperous path.

More tangibly, Pauling’s application drew the attention of several professors who provided support to the prodigious student for the remainder of his undergraduate career. Floyd Rowland, a chemical engineering professor at OAC, noted that Pauling “possesses one of the best minds I have ever observed in a person of his age, and in many ways is superior to his instructors.” Likewise, the English professor who helped Pauling with his speech earlier in the year observed that Pauling “does not expect results without hard work, but seems to delight in digging hard.” German professor Louis Bach followed suit with the keen observation later affirmed by numerous biographers:

[Pauling] is endowed with a remarkable memory in combination with good judgement, sound analytical and synthetic discrimination: a brilliant mind.

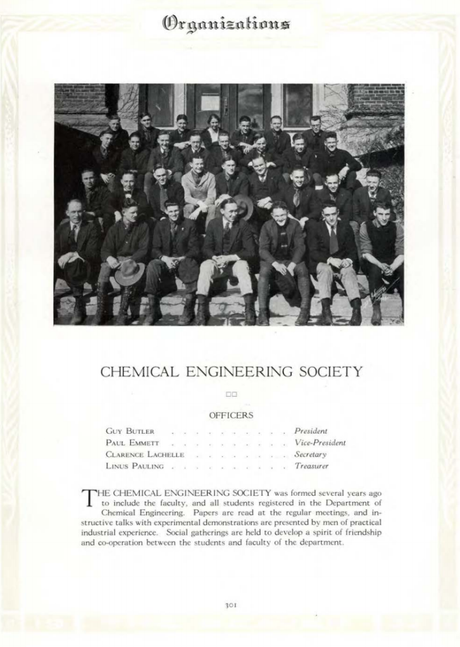

Pauling is seated at center left, in the light colored sweater.

Pauling is seated at center left, in the light colored sweater.As the year progressed, Pauling also garnered increasing attention from the school’s honor societies. First and foremost, Pauling was elected into Forum, OAC’s most prestigious and academically stringent honorary. Created six years earlier in 1914 and akin to Phi Beta Kappa, Forum was comprised of juniors and seniors who were elected by current members on the basis of their “scholastic attainment and leadership.”

Pauling was also a member of Sigma Tau, the national honor society for engineering. Like Forum, Sigma Tau was open to juniors and seniors, but its membership was selected by faculty in engineering. The organization, which was first established at the University of Nebraska in 1904, came to OAC in 1913 as the eleventh chapter in the country.

In addition, Pauling continued on as president of Chi Epsilon, the chemistry honor society. OAC’s chapter was recently formed (1918) and targeted towards chemistry students who showed “scholastic promise and who intend to make some phase of chemistry their life work.”

Pauling also devoted time to several campus clubs. He remained a member of the Chemical Engineering Society, which he had joined as a freshman and now served as treasurer. He also helped out a bit with the production of the Beaver yearbook, and was tasked, along with fellow student Ernest Abbot, to create a page documenting Forensics activities.

And as usual, Pauling earned stellar grades. Over the course of his junior year, he received all As, except for a B in Military Drill during the first quarter and, interestingly, a B in inorganic chemical engineering in the third quarter.

The 1920-21 academic year also marked the first year that Pauling was awarded the elusive A in track and field that he so desired. During his freshman year, Pauling had tried, unsuccessfully, to circumvent the school’s required gym credits by joining the track team. When he failed to make the team, Pauling simply decided to skip gym, and thus earned a failing grade for the year. Redemption came as a junior though, with an A in athletics complementing excellence in the classroom that had always come a bit easier.