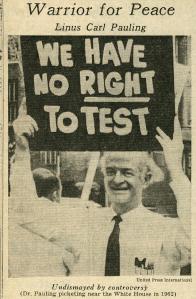

New York Times, October 11, 1963.

[Part 3 of 6]

On October 10, 1963, Linus Pauling received word that he was to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. In this, he became the first person to receive two unshared Nobel Prizes, a distinction that lives on today.

He and his wife, Ava Helen, were at Deer Flat Ranch – a property that the couple had actually purchased with the funds from Pauling’s 1954 Chemistry Prize – when the Peace Nobel was announced. Pauling was notified that morning by his daughter Linda, and the unexpected news rendered him speechless. The Big Sur ranch itself lacked a telephone, and Pauling wound up holding court at a nearby ranger station, granting several interviews and answering calls of congratulation. As reporters began to descend on the Paulings’ rural property, Ava Helen and Linus decided that it would be best to return to Pasadena to deal with whatever awaited them.

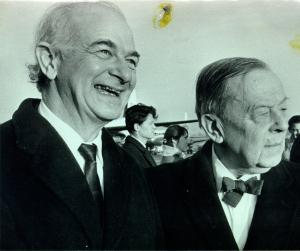

Linus Pauling and Gunnar Jahn, 1963.

As noted in Alfred Nobel’s will, a prize was to be set aside each year for “the person who shall have done the most or best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies, and for the holding and promotion of peace.” Pauling won this award in 1963 – receiving the prize that was held over and not awarded in 1962 – for his work on nuclear disarmament and his contributions to the Partial Test Ban Treaty, an agreement between the United States, Great Britain and the Soviet Union that went into effect on the same day that the Nobel award was announced.

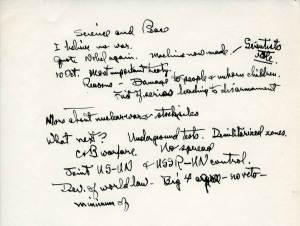

The story of why Pauling received the 1962 prize is interesting, and recounted by Pauling himself. In a confidential “note to self” that he penned on November 21, 1962 – about eleven months before his Peace Prize announcement – Pauling documented a meeting that he had held that day with Gunnar Jahn. Jahn was chair of the Norwegian Nobel Committee from 1941 to 1966.

In his memo, Pauling wrote

On the morning of Tuesday 13 Nov., Gunnar Jahn telephoned me at the Bristol Hotel, Oslo, and asked us to come to his office at 11 A.M. There he said to Ava Helen and me, in the presence of his secretary, Mrs. Elna Poppe, “I tried to get the Committee [of which he is the Chairman] to award the Nobel Peace Prize for 1962 to you [L.P.]; I think that you are the most outstanding peace worker in the world. But only one of the four would agree with me. I then said to them ‘If you won’t give it to Pauling, there won’t be any Peace Prize this year.'”

And indeed, there was not.

Pauling received two nominations for the Peace Prize in 1961, as well as one more in 1962 and another in 1963. The year that he received the Prize, he was nominated by Gunnar Garbo, a Norwegian journalist, politician and ambassador. And although many feel that Linus should have been nominated for the Peace Prize alongside Ava Helen – his long-time collaborator and inspiration in their shared peace effort – none of his Peace nominations was submitted as a split award.

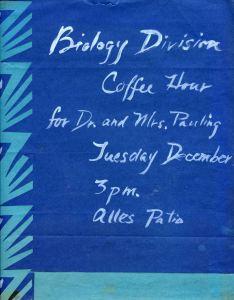

Flyer for the Biology Department coffee hour honoring Pauling’s receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize. December 3, 1963.

In a marked contrast from his Chemistry Prize, Pauling’s Peace award was not celebrated domestically with a lavish ceremony. By 1963, Pauling’s activities in the peace realm had led to increased tensions at Caltech, and across the Institute, response to his Peace Prize was mixed at best. His own research group was overjoyed at the honor, but the Caltech administration was unusually quiet concerning the prize and did not plan any sort of celebration in Pauling’s honor.

Although Linus and Ava Helen both felt that the Prize was vindication enough of the work they had done and the positions that they had taken, neither was at all satisfied with how the situation had unfolded at Caltech. With the prize money from the Peace award forthcoming, the duo now had the flexibility to leave the Institute and pursue their work elsewhere. Pauling announced his decision to do exactly this in October, just a week after finding out that he had won the prize, and after forty-one years of employment at Caltech.

By early December, although he had already cleared out his office, colleagues in the Biology department invited Pauling back to campus for a small gathering over coffee to honor his Nobel Peace Prize. This event proved to be the only recognition of Pauling’s achievement hosted at the Institute.

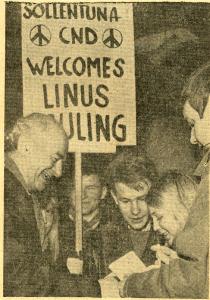

Image published in Arbeiderbladet, December 11, 1963. Annotaions by Linus Pauling.

Once in Scandinavia, the festivities likewise differed some from what he had experienced in Stockholm in 1954. Pauling was awarded the Peace Prize on December 10, 1963 at Oslo University in Norway, an event attended by King Olav VI, Crown Prince Harald, and scores of additional Norwegian leaders and diplomats. (In his will, Nobel decreed that the Peace Prize ceremony be held separately from the other Nobel Prize awards, which take place in Stockholm, Sweden.)

Also presented at the ceremony was the 1963 Peace Prize, granted jointly to the International Committee of the Red Cross and the League of the Red Cross Societies. The International Committee had won the Peace Prize twice previously, in 1917 and 1944, and their 1963 centennial played a role in the selection of the two groups for the prize. As Pauling is the only person to have received two unshared Nobel Prizes, so too is the Red Cross unique in having been fundamental to four Peace Prizes – three received or shared by the organization, and another through affiliation with the group’s founder, Henry Dunant, co-honored with the very first Nobel Peace Prize in 1901.

At the ceremony, Pauling was called out for his campaign “not only against the testing of nuclear weapons, not only against the spread of these armaments, not only against their very use, but against all warfare as a means of solving international conflicts.” Gunnar Jahn – Pauling’s champion from a year before – further explained that he was the natural choice for the 1963 award, due to the successful negotiation of the Partial Test Ban Treaty that July in Moscow.

Verdensgang (Olso), December 14, 1963.

Despite Jahn’s certainty on the matter, Pauling’s nomination had been made in the face of severe criticism, mostly centering on claims that Pauling was a Communist, that President John F. Kennedy should have received the award, or that Martin Luther King, Jr. was a better choice. In his acceptance speech, Pauling explained that he believed the award to be a recognition not only of his work but also that “of the many other people who strive to bring hope for permanent peace to a world that now contains nuclear weapons.”

For Pauling, his wife was most prominent among the multitudes who had worked alongside him to pursue peace. He made special note of her contributions in his formal Response at the Nobel event.

I wish that Alfred Nobel had not been a lonely man. I have not been lonely. Since 1923 I have had always at my side my wife, Ava Helen Pauling. In the fight for peace and against oppression she has been my constant and courageous companion and coworker. On her behalf, as well as my own, I express my thanks to Alfred Nobel and to the Nobel Committee of the Norwegian Storting for the award of the Nobel Peace Prize for 1962 to me.

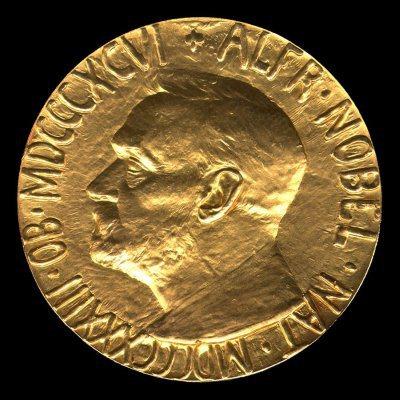

Pauling’s Nobel Peace medal, obverse.

Designed by Norwegian sculptor Gustav Vigeland, the Nobel Peace Prize medal features an image of Alfred Nobel that is different from the other medals, though it is accompanied by the same inscription – “Alfred Nobel” and his years of birth and death. The reverse side of the medal portrays three men forming a fraternal bond and is inscribed with the words Pro pace et fraternitate gentium, which can be translated as “For the peace and brotherhood of men.” On the outer edge, the words “Prix Nobel de la Paix”, the relevant year, and the name of the Nobel Peace Prize Laureate are engraved.

Pauling’s Peace medal, reverse.

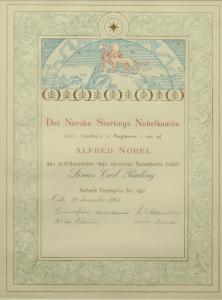

All Nobel Prize medals are accompanied by a diploma and a letter certifying the amount of the given year’s monetary award. The cash prize in 1962 was $50,000, or approximately $386,204.00 in today’s dollars. This sum amounted to roughly three years of Pauling’s Caltech salary.

Pauling’s Nobel Peace certificate.

New York Times, October 11, 1963.

In his Nobel acceptance speech, delivered a day after his Response, Pauling compared the desire of Alfred Nobel himself to create “a substance or a machine with such terrible power of mass destruction that war would thereby be made impossible forever,” to the hydrogen bomb against which the peace movement was working in 1963. And though the creation and use of the atomic bomb during the Second World War had not led to peace, Pauling remained hopeful that peace would be attained, as nuclear weapons had now made a survivable war impossible.

“I believe that there will never again be a great world war,” he said, “a war in which the terrible weapons involving nuclear fission and nuclear fusion would be used.” Pauling felt that no dispute could justify the use of such a weapon, and that the threat of larger-scale retaliation would prevent first strikes. This sentiment was present in many of the speeches and articles that he penned during this period. In his Nobel lecture, Pauling expanded on the idea by explaining that

The world has now begun its metamorphosis from its primitive period of history, when disputes between nations were settled by war, to its period of maturity, in which war will be abolished and world law will take its place.

And just as scientists had played a role in the development of weapons of war, so too would they be central to promoting peace in the nuclear age, because of the power that their informed opinions carried and the research that they could conduct to show just how harmful these bombs were.

In this, Pauling specifically mentioned the Pugwash Conferences series, which he believed “permitted the scientific and practical aspects of disarmament to be discussed informally in a thorough, penetrating, and productive way, and have led to some valuable proposals.” Because of this, he felt the conferences – with which he had been active – to have been very helpful in seeing the Partial Test Ban Treaty through to ratification.

Stockholmns Tidinigen, December 19, 1963.

But there was still much work to do, in part because many people had not yet accepted disarmament as a valid route to maintaining peace. For Pauling, disarmament was only a piece of the solution. He felt that, for one, China, as the world’s most populous nation, needed to be accepted into the global community and recognized as a nation. Doing so would allow the Chinese People’s Republic, a nuclear state, to join the disarmament agreement already signed by the United States and Soviet Union.

Pauling further proposed a joint system of control for nuclear stockpiles, one which would require consent from the United Nations before a weapon could be used. While admittedly a lofty ambition, Pauling believed that “even a small step in the direction of this proposal, such as the acceptance of United Nations observers in the control stations of the nuclear powers” would decrease the probability of war, and doubly so if the proposal was paired with a system of inspection aimed at preventing the further production of biological or chemical weapons. Advancements in this direction, Pauling believed, not only improved the odds for the long-term survival of the human race, but would also usher in a better life for all humans through the improvement of social, political, and economic systems.