Image is captioned: “Prof. Linus Pauling stole the show at the Nobel banquet with his cheerful laugh.” Credit: MT söndag, 1954.

[Part 2 of 6]

Nominated at least seventy times for prizes in chemistry, medicine and peace, Linus Pauling is the only person to have ever won two unshared Nobel Prizes. The Chemistry Prize, received in 1954, would be his first; he received the second prize in 1963 for Peace.

By the time that Pauling won the Chemistry Nobel in 1954, many believed the prize to be long overdue. Pauling himself had started to feel that he might never win one because his most important work to that point comprised a body of research rather than the singular specific discovery for which Nobel Prizes had usually been awarded. Pauling also knew that he had been nominated in 1953 by Albert Szent-Györgyi, but did not receive the support of the Nobel Committee.

News of Pauling’s Chemistry Prize spurred a huge influx of correspondence and congratulations from colleagues and friends, both locally and globally. The award ceremony also prompted a world tour that lasted almost five months, beginning with two weeks of sightseeing in Norway and Sweden as a family.

Image is captioned: “Prof. Linus Pauling stole the show at the Nobel banquet with his cheerful laugh.” Credit: MT söndag, 1954.

Prior to 1954, Pauling had been nominated for the Chemistry Prize nearly every year beginning in 1940. And although he was nominated several times to share a prize with various colleagues, these individuals were not always people with whom he had worked, but also included fellow scientists who had focused on similar projects as had Pauling.

In 1954 Pauling was nominated thirteen times for the Chemistry Prize, twice with a partner: German organic chemist Hans Lebrecht Meerwein and American organic chemist Robert Burns Woodward. Five of the 1954 nominators had also submitted Pauling’s name in preceding years, colleagues including Edward Doisy, Jacques Hadamard, Albert Szent-Györgyi, Arne Tiselius, and Karl Freudenberg. New and notable nominations in 1954 came from French chemists Irène and Frédéric Joliot-Curie, and the American astronomer Harlow Shapley.

In his will, Alfred Nobel stipulated that one prize was to go to “the person who shall have made the most important chemical discovery or improvement.” In 1954 Pauling was honored “for his research into the nature of the chemical bond and its application to the elucidation of the structure of complex substances.” Pauling’s prize marked the first time that the Nobel Committee had recognized a collection of work rather than “the most important chemical discovery or improvement” of a given year.

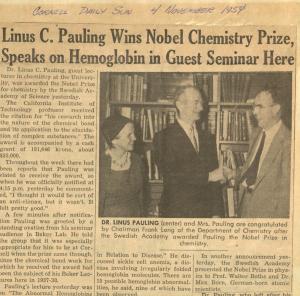

Pauling learned that he was to receive the Nobel Prize in Chemistry on November 3, 1954, just 45 minutes before giving a lecture at Cornell University. He recalled later that he “had a little trouble with the seminar.” Soon after finding out that he had won the Nobel, congratulations began to come from his nominators, who were colleagues and friends from around the world. Hundreds of letters and telegrams soon followed.

The tenth American to win the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, Pauling was honored by the Nobel Committee for his study of the structure of matter and of the seemingly invisible forces that hold together the building blocks of all matter. When asked for his thoughts on this work, Pauling first explained that it was the support and environment that fellow scientists and collaborators had created at Caltech that helped him to win the prize. He likewise noted that he had been able to develop his theories as a result of many years worth of work – by him and others – on x-ray crystallography and the behavior of electronically irradiated chemicals.

Stage presentation of “The Road to Stockholm: The Appalling Life of Linus Pauling,” 1954. Verner Shomaker and Ken Hedberg stand near the microphone.

The Paulings began their trip to Stockholm with a bon voyage party thrown by Caltech faculty on December 3rd. The gala was held at the Caltech Athenaeum and attended by 353 people – the largest dinner served there up to that point. In addition to a meal, the evening’s events included an ode to Pauling performed by a muse on the harp.

Afterward, the dinner attendees joined others at Caltech’s Culbertson Hall for a showcase celebrating Pauling. This lighthearted affair included the performance of a skit titled “The Road to Stockholm,” a humorous tale of Pauling’s scientific work and life as performed by Pauling’s colleagues, who called themselves the “Chemistry-Biology Stock Company.” Afterward, a buoyant Pauling told the media that the event had been the “high point of my life.”

Once in Scandinavia, Ava Helen and Linus were accompanied by their children Linus Jr. (joined by his wife, Anita), Peter, Linda, and Crellin. For the duration of their visit, the entire Pauling family found themselves on prominent display in the Swedish press.

From an article, “Festivitas och Gladje Kring Nobelbanketten”, Dagens Nyheter, December 12, 1954.

A total of six Nobel Prizes can potentially be presented in any given year: one each in the fields of physics, chemistry, medicine, literature, peace, and the economic sciences. And in 1954 all but the Physics Prize – awarded to Max Born and Walter Bothe for their “fundamental research in quantum mechanics, especially in the statistical interpretation of the wave function” – were granted to Americans. Laureates alongside Pauling included Ernest Hemingway (Literature), and Drs. John Enders, Thomas Wellers, and Frederick Robbins (Medicine). In 1954 no Peace Prize was awarded, and the Economics Prize was not established until 1968.

Pauling described the Nobel Ceremony in Stockholm as “very impressive…it must be one of the most impressive ceremonies in the modern world.” The pageantry marking Pauling’s decoration began on December 9th, with a reception hosted by the Royal High Chamberlain of Sweden, who was also President of the Nobel Foundation. This gathering was followed by a formal dinner hosted by the Secretary of the Swedish Academy.

The following day, the laureates received their Nobel Prizes from King Gustav Adolph at the Stockholm Concert Hall. Following that was the Nobel Dinner, held in the Gold Room of the Stockholm City Hall. The dinner coincided with a torchlight parade organized by Swedish university students, and Pauling was honored to deliver a response to the students on behalf of all the year’s Nobel laureates, in which he famously encouraged the students to always think for themselves.

Pauling’s Nobel lecture was delivered the next day, on December 11th. Titled “Modern Structural Chemistry,” the talk outlined Pauling’s advancements in structural and inorganic chemistry. Pauling situated this work within a broader time frame to both add context to his own achievements in the field and to connect them with the work of others. As he interpreted the historical evolution of modern structural chemistry, he explained

The development of the theory of molecular structure and the nature of the chemical bond during the past twenty-five years has been in considerable part empirical – based upon the facts of chemistry – but with the interpretation of these facts greatly influenced by quantum mechanical principles and concepts.

He concluded his remarks with a prophetic statement on what he saw coming in the future:

We may, I believe, anticipate that the chemist of the future who is interested in the structure of proteins, nucleic acids, polysaccharides, and other complex substances with high molecular weight will come to rely upon a new structural chemistry, involving precise geometrical relationships among the atoms in the molecules and the rigorous application of the new structural principles, and that great progress will be made, through this technique, in the attack, by chemical methods, on the problems of biology and medicine.

His lecture delivered, Pauling and his wife rounded out their Nobel adventure at the royal palace as dinner guests of Sweden’s King and Queen.

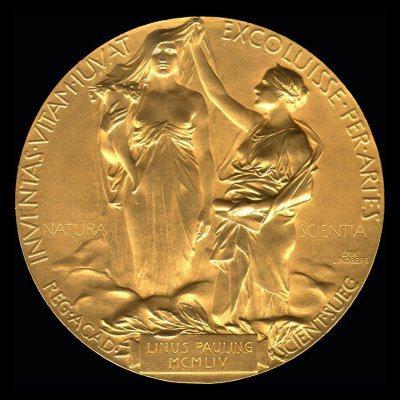

The Nobel Chemistry medal depicts nature, in the form of the goddess Isis, emerging from clouds and holding a cornucopia in her arms. The veil that would cover her face is held back by the Genius of Science. The inscription on the medal reads: Inventas vitam juvat excoluisse per artes which, loosely translated, means “And they who bettered life on earth by their newly found mastery.” (Word for word: “inventions enhance life which is beautified through art.”) Below the goddess and Genius, the name of the laureate is engraved on a plate adjacent to the text “REG. ACAD. SCIENT. SUEC.” which stands for The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

The medal itself was designed by Swedish sculptor and engraver Erik Lindberg. The obverse side of the medal depicts Alfred Nobel in profile, and the years of his birth and death.

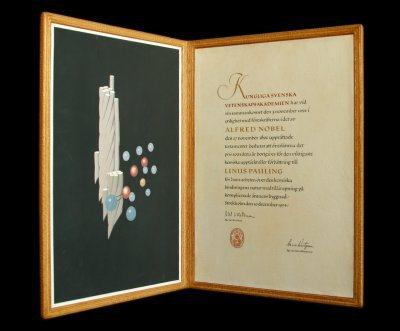

Accompanying Pauling’s medal was a Nobel diploma and a monetary award. In 1954 the prize award amount was $35,000, or approximately $305,517.00 in today’s dollars. When asked how he would spend it, Pauling responded, “most scientists have plenty of old bills to pay.”

Following the ceremonies in Sweden, Ava Helen and Linus toured the world for almost five months. They spent Christmas in Bethlehem and later traveled all throughout Asia, visiting India and Japan in particular, and meeting with colleagues at universities and elsewhere. Pauling believed that it was especially important for him to visit India as, earlier in the year, he had been denied a passport to travel to the subcontinent, though he had been invited personally by India’s Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru.

The Paulings were well-received throughout their world travels, and they returned home from their trip even more determined to fight for peace and global disarmament. This work which would eventually lead to another Nobel Prize, accepted some nine years later.