Linus Pauling, 1940s

Linus Pauling, 1940s[Happy Linus Pauling Day! Today we celebrate what would have been Pauling’s 119th birthday by continuing to dive deep into his lengthy and important association with the Guggenheim Foundation.]

During Linus Pauling’s tenures on the Committee of Selection and the Advisory Board for the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, he was able to meet in person with many of the applicants whose proposals he was charged with reviewing. By conducting a face-to-face interview, Pauling was able to press applicants on particular points while also making suggestions on how they might edit their submissions to improve their chances. After each of these interviews, Pauling would report on what he had learned to the Foundation’s Secretary, Henry Allen Moe.

The Foundation’s guiding documents stipulated that Fellowships be made available to anyone pursuing some form of research or exploration in their chosen field, and that applicants need not be academics. In August 1945, Pauling spoke with one such applicant, Luella A. Huggins, a lawyer from Kerman, California who was interested in the application of psychology to social problems, especially crime. Huggins had unsuccessfully applied for a Fellowship in 1941 and wanted to try again.

After meeting with her, Pauling came away unimpressed. “She is an uninspired person,” he wrote to Moe, “of middle age, who has not published anything, nor completed a manuscript… I think that she could never be a satisfactory recipient of a fellowship.” And with that, Pauling assumed the matter had been settled.

Huggins apparently came away from the meeting with a different impression. During their time together, Pauling had told Huggins that she needed to have more publishing experience, and within two weeks she sent him a potential article and a sample chapter for a proposed book, informing him that publishers were already interested. Huggins explained that she did not have the time or money to write since beginning her legal career ten years earlier. Once she published her book however, she planned to give up law as she only took it up to pay off debts. For Huggins, a Guggenheim Fellowship represented a chance to start over.

To further her candidacy, Huggins asked Pauling for his advice on approaching other members of the Committee of Selection. Pauling was brief in his reply, telling Huggins that her manuscripts were interesting and that she should move forward with her application but not reach out to each Committee member. In the end, Huggins came away disappointed again when she once more did not receive a Fellowship. That said, she did eventually succeed in self-publishing her book, Behavior and Law, in 1959.

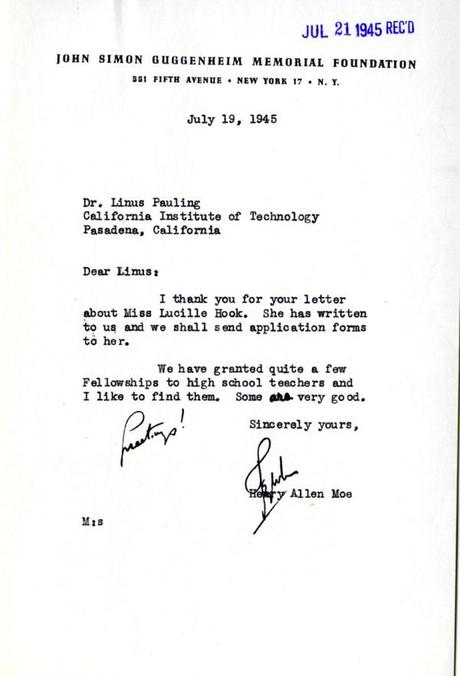

That same summer, Pauling spoke with another applicant outside of the academy, Lucyle Hook, a high school teacher in Scarsdale, New York. Hook was studying a perceived change, as Pauling reported to Moe, “from the masculine Shakespearian drama (to use her words) to the more feminine modern drama.”

Over the past several years, Hook had devoted her summers to research, first going to England and then the Huntington Library in San Marino, California. During her most recent research trip to southern California, Hook visited Pauling at Caltech and made a good first impression as “a serious and lively person, with a real interest in life.” Unlike Luella Huggins, Pauling initially thought it a good idea to give Hook some support. Moe concurred, telling Pauling that he took special pleasure in finding worthy high school teachers to fund.

Hook’s candidacy took a turn for the worse however, when she sent to Pauling her manuscript on the Restoration era actresses Elizabeth Barry and Anne Bracegirdle. “I am afraid that Dr. Hook is an uninteresting writer,” Pauling reported. “[S]he is far less interesting as a writer than as a talker. Moreover, her writing seems to me to be poor. Her paragraphs are disconnected, her sentences are vague, and her words are used without sufficient attention to their meaning.”

With this new information in hand, Pauling withdrew his previously strong support for Hook, though he allowed that input from external referees and references would shape his final opinion. In the end, Hook was not awarded a Fellowship but soon became a professor of English at Barnard College and succeeded in publishing her work.

Pauling spent most of the 1947-48 academic year as a visiting professor at Oxford, but even there he continued to meet with people about Fellowships. One person with whom he spoke was North Carolina State University historian John Shirley, who wanted to renew an existing award so he could spend time more in England studying the papers of the astronomer and geographer Thomas Harriot.

One of the early settlers of Raleigh, North Carolina, Harriot authored a volume, Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, after returning to England in 1588. Shirley wished to study this book in depth, and with his Fellowship renewed, he guessed that he could complete his project within a year. (Absent additional funding, he estimated completion in six to eight years.) Pauling judged Shirley to be a hard worker with interesting material, but was disappointed that he had little knowledge of modern science, a trait that colored Pauling’s opinion of many scholars with whom he interacted. Shirley’s Fellowship was not renewed.

Not every meeting resulted in a definitive judgment. In 1952 Pauling met with George A. Zentmyer, a plant physiologist at the University of California, Riverside, and a candidate about whom Pauling struggled to form a strong opinion. On the one hand, Pauling found Zentmyer to be very likeable, but on the other he did not seem to know enough about chemistry. His abilities as a plant physiologist could potentially make up for this deficiency, but Pauling was not certain and thought it best for the committee to decide. Pauling also frowned upon Zentmyer’s proposal to go to the University of Wisconsin and the Connecticut State Experiment Station, thinking it more productive to propose travel to Europe instead.

In the end, Zentmyer made it easy on Pauling by withdrawing his application — a trip to South America got in the way of the Guggenheim plans. Pauling suggested that he reapply the next year; Zentmyer ultimately received funding in 1964.

Scientists and humanists were not the only ones to benefit from Guggenheim Fellowships — many artists did as well. And when applications from scientists started to diminish during the Second World War, Moe encouraged Pauling to recommend people from other groups.

Pauling’s first recommendation of this sort was for his friend Barse Miller, a watercolorist. Miller’s son had recently died in an auto accident and, partly to salve his grief, Pauling talked him into applying for a Fellowship even though the deadline had passed. The Committee awarded Miller the Fellowship, but he could not immediately accept it as he had been called into active military duty and asked to paint Army scenes in the Pacific. Once the war was over, Miller fulfilled his Fellowship in 1946.

Another artist whom Pauling recommended was the experimental filmmaker Oskar Fischinger, who had briefly worked on the animation for the scene of Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in the Disney film, Fantasia. Fischinger eventually quit because the studio decided to make the animation less abstract.

Pauling first saw Fischinger’s black-and-white films while in Europe and was very impressed. In 1951 Fishchinger was in Los Angeles screening his recent color films, The United States March and Motion Painting No. 1, and Pauling made a point of attending to see the new work and learn more about Fischinger’s technique. Though he preferred the black-and-white films, Pauling agreed that Fischinger’s more recent films took his earlier ideas in a whole new direction.

Fischinger’s Guggenheim idea was to produce “Space Paintings” in color and motion. Pauling was unsure how he would accomplish this, but was confident that he could figure it out and, more generally, was supportive of Fischinger’s desire to contribute to experimental film. When Pauling spoke with Fischinger, he found him to be quiet, modest, and enthusiastic. Moe appreciated Pauling’s recommendation and, as his “experimental-film expert,” took his opinion very seriously. Despite all of this groundwork however, Fischinger never formally applied for funding.

Linus Pauling’s work with the Guggenheim Foundation took him well beyond his home in chemistry but did not dissuade him from making strong judgments. Rather than relying on his knowledge of content in these cases, Pauling instead attempted to elaborate on the reasons why a candidate’s work was or was not interesting to him. And as was the case with science-related applicants, Pauling’s judgments oftentimes lined up with the Foundation’s final decisions on granting fellowships.