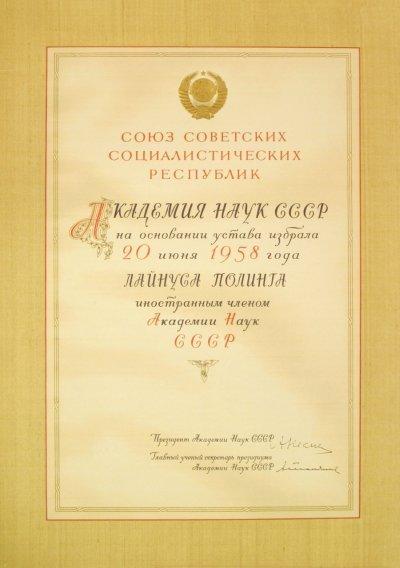

On June 20, 1958, in the midst of the Cold War and almost exactly 25 years after being inducted into the National Academy of Sciences, Linus Pauling was unanimously approved for inclusion in the Akademia Nauk (Academy of Sciences) of the USSR. Founded in 1724 during the reign of Peter the Great and charged with conducting national research and overseeing scientific publications, the Academy had attained a position of major importance in Soviet society and its domestic members were among the highest paid individuals in the communist country.

Though often critical of Soviet leaders, Pauling never had any qualms about engaging in scientific exchanges with Russian scientists, even during the frostiest years of U.S-Soviet tensions. In one particular instance, a year prior to being honored by the Soviet Academy, Pauling had extended invitations to two of its members to visit Caltech and deliver lectures on their current research. At the time however, the greater Los Angeles and San Francisco areas had both been closed “to anybody holding a Russian passport,” and the scientific invitees were unable to accept Pauling’s offer.

In response, Pauling made a point of criticizing the U.S. Department of State, claiming that its policies ran counter to a recent commitment by the federal government to increase “freer exchange of information and ideas,” to push that “all censorship [be] progressively eliminated” and to “further exchanges of persons in the professional, cultural, scientific and technical fields.”

Pauling’s award notification from the Academy expressed “the hope that your election as a foreign member will promote further strengthening of the bonds between scientists of the USA and the Soviet Union.” And while Pauling accepted the offer warmly, others cast a very skeptical eye toward his embrace of this particular decoration.

While the responsibilities of his membership were purely honorary and the Academy insisted that he was being recognized for his scientific accomplishments, many media outlets, including the New York Times, suspected that the decision had been politically motivated. In his response, Pauling noted that the Soviets “have been strongly critical of my work in the past,” pointing out in particular that, in 1951, the Academy had deemed his theory of resonance to be “reactionary” and “bourgeois.” In the years since, Pauling supposed that the Soviets had “learned that you can’t mix politics up with science.”

Pauling was well-aware that his acceptance of the Academy’s nomination would garner criticism, but for him it was worth it to take a stand in favor of academic freedom. In a statement to the Associated Press, Pauling affirmed his strong belief “in the importance of improving international relations in every way” and expressed enthusiasm at the idea of “becoming better acquainted with the scientists in the USSR.” The letters of congratulation that he received from his colleagues indicate that this point of view was shared by many.

Pauling did not travel to the Soviet Union to accept his award, but he did address the topic of his membership in several lectures that he delivered during the summer of 1958. One talk, delivered at Antioch College on the day of his nomination, used the honor as a rhetorical starting point for a deeper discussion of a path toward reducing the risk of nuclear was. In this, Pauling emphasized that the United Nations must be strengthened, that nuclear weapons tests must cease, and that the world choose to recognize the communist government in China.

The president of Antioch College sent Pauling a follow-up letter indicating that the local media had mostly accepted Pauling’s ideas on merit, though the Dayton Daily had refused to report on the event at all due to Pauling’s membership in the Soviet Academy.

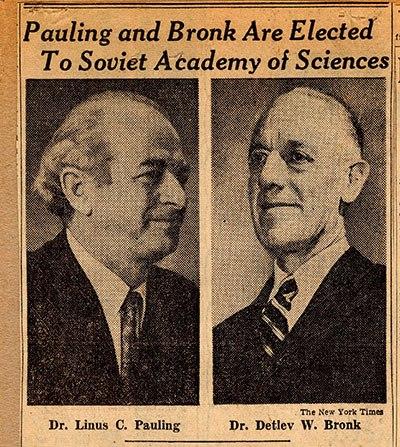

In addition to Pauling, one other American was added to the Soviet Academy in 1958. Detlev Bronk, a well-known and accomplished scientist, had also served as president of Johns Hopkins University from 1948-1953. During this time he created the Hopkins Plan, a successful approach to student advancement that emphasized allowing undergraduates to choose their own rate of progression through their course of study.

Bronk and Pauling were also friends who corresponded with one another about issues both personal and professional well before their induction into the Academy. Their bond had been formed by shared scientific interests, but also by a similar worldview. Notably, Bronk had shown himself to be a defender of academic liberty by speaking out in favor of a professor who had been accused by Senator Joseph McCarthy of communist involvement in the early 1950s.

Another relevant and significant name from this time period was Bruno Pontecorvo, who was inducted into the Academy alongside Pauling in 1958. Pontecorvo, a highly regarded Italian-born physicist, was living in the US and working on atomic research when he disappeared in 1950. Considered missing for several years, Pontecorvo eventually appeared on Soviet television, at which point it was understood that he had defected. Moreover, it later became clear that the scientist had risen to a position of authority within the Soviet nuclear development program.

Confirmation of Pontecorvo’s defection came as a shock, and some feared that Pauling would follow in his footsteps. Needless to say, this did not come to pass. Pontecorvo, on the other hand, remained in the USSR and worked under the Russian flag until his death in 1993.