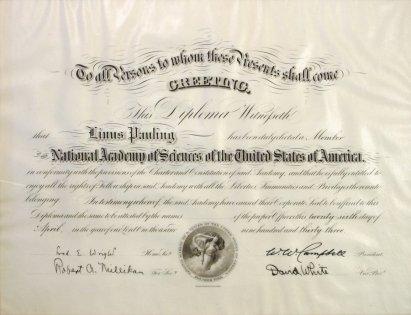

Since its formation in 1863, the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) has been a home of sorts for the country’s (and a few of the world’s) most distinguished scientists, and on April 26, 1933, at the age of 32 years and 2 months, Linus Pauling became the youngest current member of the group. Pauling was accepted into this distinguished body for his contributions to many scientific fields, but most significantly chemistry. And though he was still early in his career, his induction served as validation of his scientific excellence while also reflecting the growing global influence of his research and writing.

The NAS was established by an act of Congress during the presidency of Abraham Lincoln and was charged with playing a central role in advancing the nation’s scientific research agenda and in communicating with policymakers about applying scientific breakthroughs to improve the lives of Americans. Induction into the Academy was, and remains, out of reach for all but the most accomplished of researchers. Membership has also always come with responsibilities: at the time of his induction, Pauling was made to understand that he was obligated to respond to every Academy summons and to “serve the government without expectation of compensation.”

At the time that Pauling joined, there were 265 NAS members (as of 2018 there are nearly 500), only two of whom were women. Forty-four members hailed from other countries including Canada and several European nations. Within the U.S., the NAS made it a priority to pull members from every region of the country, and also urged states that had not been home to any members – states including Oklahoma, New Mexico, Washington, and Nevada among others – to produce more prominent scientists. By 1933, Pauling’s birth state, Oregon, had only produced one member (Pauling) whereas the state in which he lived, California, was home to forty-five residing members.

In addition to diversifying the geographic reach of its membership, the Academy also sought to bring in more younger faces. It had several reasons for doing so. For one, younger members were more likely to spark a connection with high school and college-age students across the country who might eventually grow into the scientific leaders of tomorrow. Of equal or greater importance was the fact that, amidst the ravages of the Depression, the Academy required energy, enthusiasm and creativity to keep itself moving forward, and younger scientists were seen as more likely to bring that about.

Pasadena Post, September 27, 1933

Of the 265 Academy members in Pauling’s cohort, 159 were older than 60, and 58 had reached the age of 70 or more. The average age of new inductees was 49 (45 for chemists) and the typical age of an NAS member was 62. While the youngest inductee ever, Edward C. Pickering (1846-1919), was about six years younger than Pauling when he was elected in 1873, he had long since passed away by the date of Pauling’s inclusion. Indeed, by 1933, only three members of the NAS were under 40 years of age, so Pauling certainly stuck out.

Though Pauling ticked the boxes of a younger member who represented, if obliquely, a new part of the country, his selection was clearly predicated on merit. Pauling’s research program at the time included work that would soon become legendary. By using x-ray diffraction techniques to determine the structure of crystals, he had made great headway toward unraveling the mysteries of molecular structure, and in 1933 he published his fifth, sixth, and seventh papers in his epic series on the nature of the chemical bond. The import of these publications was quickly recognized by his peers, and when Pauling was added to the Academy he was the only selection made for the Chemistry section.

Along with much of the rest of the country, the academy that Pauling joined was struggling mightily during terrible economic times. Wrestling with an onslaught of major problems, many cash-strapped legislators were, in the words of NAS President W.W. Campbell, “unsympathetic and severely hostile” to the idea of maintaining federal funding for scientific research. Campbell argued forcefully on behalf of maintaining the support for the NAS, suggesting that

…the products of research and invention in the domain of the physical and biological sciences have been more potent in advancing the state of civilization on the earth from its low level of the fifteenth century to its high level in the twentieth century than have all other forces combined.

Fortunately for the Academy, fears that cuts in funding would relegate American universities to the status of “higher high schools” prevailed, and the NAS was allocated $250,000 to distribute to researchers during the 1933 fiscal year.

As time moved forward, the country stabilized and so did the Academy. And for a period after the war, the NAS also nearly played a very influential role in Pauling’s life. In 1947 he was nominated to serve as president of the group and fully intended to pursue this opportunity, but was compelled to remove his name from consideration when he was named Eastman Visiting Professor at Oxford University for that same year. A year later, Pauling ran successfully for the presidency of the American Chemical Society and occupied that office in the NAS’s stead.