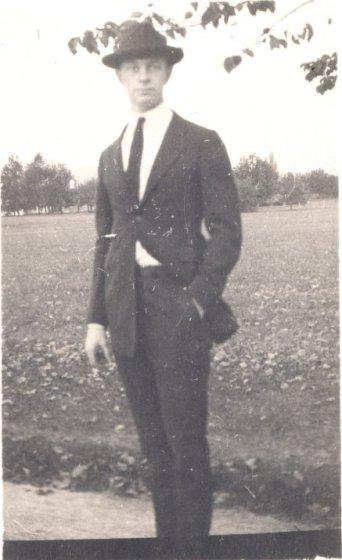

Pauling posing at lower campus, Oregon Agricultural College, ca. 1917.

[An examination of the end of Linus Pauling’s life, part 1 of 4]

In 1917, at sixteen years of age, Linus Pauling wrote in his personal diary that he was beginning a personal history. “My children and grandchildren will without doubt hear of the events in my life with the same relish with which I read the scattered fragments written by my granddad,” he considered.

By the time of his death, some seventy-seven years later, Pauling had more than fulfilled this prophecy. After an extraordinarily full life filled with political activism, scientific research, and persistent controversy, Pauling’s achievements were remembered not only by his children, grandchildren and many friends, but also by an untold legion of people whom Pauling himself never met.

Passing away on August 19th 1994 at the age of 93, Pauling’s name joined those of his wife and other family members at the Oswego Pioneer Cemetery in Oregon. What follows is an account of the final three years of his life.

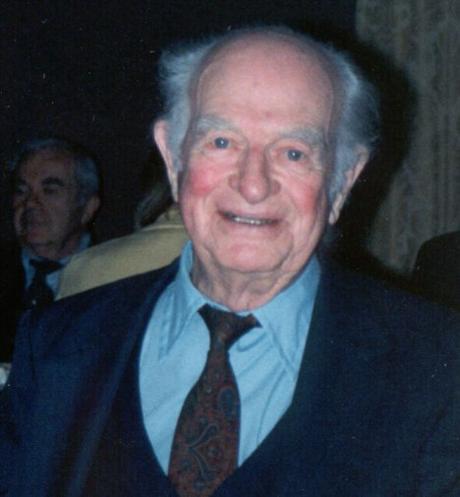

Linus Pauling, 1991.

In 1991, Pauling first learned of the cancer that would ultimately take his life. Having experiencing bouts of chronic intestinal pain, Pauling underwent a series of tests at Stanford Hospital that December. The diagnosis that he received was grim: he had cancer of the prostate, and the disease had spread to his rectum.

Between 1991 and 1992, Pauling underwent a series of surgeries, including the excision of a tumor by resection, a bilateral orchiectomy, and subsequent hormone treatments using a nonsteroidal antiandrogen called flutamide. During this time, Pauling also self-treated his illness with megadoses of vitamin C, a protocol that he favored not only for its perceived orthomolecular benefits, but also as a more humane form of treatment than chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Pauling’s interest in nutrition dated to at least the early 1940s, when he had faced another life-threatening disease, this time a kidney affliction called glomerulonephritis. Absent the aid of contemporary treatments like renal dialysis – which was first put into use in 1943 – Pauling’s survival hinged upon a rigid diet prescribed by Stanford Medical School nephrologist, Dr. Thomas Addis. At the time a radical approach to the treatment of this disease, Addis’ prescription that Pauling minimize stress on his kidneys by limiting his protein and salt intake, while also increasing the amount of water that he drank, saved Pauling’s life and led to his making a full recovery. Though his famous fascination with vitamin C would not emerge until a couple of decades later, Pauling’s nephritis scare instilled in him a belief that dietary control and optimal nutrition might effectively combat a myriad of diseases. This scientific mantra continued to guide Pauling’s self-treatment of his cancer until nearly the end of his life.

Pauling also believed that using vitamin C as a treatment would, as opposed to chemotherapy, allow him to die with dignity. Were his condition terminal and his outlook essentially hopeless, Pauling felt very strongly that he should be permitted to pass on without “unnecessary suffering.” Pauling’s wife, Ava Helen, had died of cancer in December 1981. She too had refused chemotherapy and other conventional approaches for much of her illness, a time period during which Linus Pauling had helped his wife the only way he knew how: by administering a treatment involving megadoses of vitamin C. This attempt ultimately failed and, by his own admission, Pauling never really recovered from his wife’s passing.

Nonetheless, Pauling continued to lead research efforts to substantiate the value of vitamin C as a preventive for cancer and heart disease in his capacity as chairman of the board of the Linus Pauling Institute of Science and Medicine (LPISM). By the time of his own diagnosis in 1991 however, the Institute was in a desperate financial situation, several hundred thousand dollars in debt and lacking the funds necessary to pay its staff.

In 1992, while he recovered from his surgeries and managed his illness, Pauling continued to act as chairman of the board of the LPISM. No longer able to live entirely on his own, he split his time between his son Crellin’s home in Portola Valley, California, and his beloved Deer Flat Ranch at Big Sur. When at the ranch, Pauling was cared for in an unofficial capacity by his scientific colleague, Matthias Rath. Pauling was first visited by Rath, a physician, in 1989, having met him years earlier in Germany while on a peace tour. Rath was also interested in vitamin C, and Pauling took him on as a researcher at the Institute. There, the duo collaborated on investigations concerning the influence of lipoproteins and vitamin C on cardiovascular disease.

Not long after Pauling’s cancer diagnosis, a professor at UCLA, Dr. James Enstrom, published epidemiological studies showing that 500 mg doses of vitamin C could extend life by protecting against heart disease and also various cancers. This caused a resurgence of interest in orthomolecular medicine, and it seemed that Pauling and Rath’s vision for the future of the Institute was looking brighter.

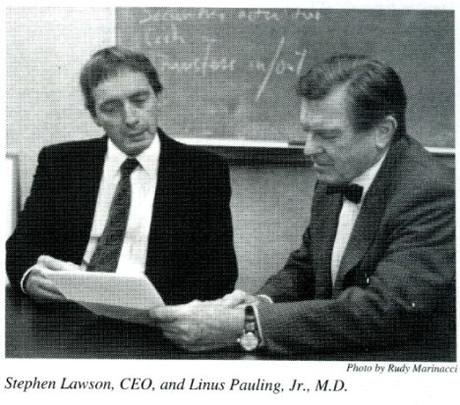

As it happened, this bit of good news proved to be too little and too late. LPISM had already begun to disintegrate financially, its staff cut by a third. The Institute’s vice president, Richard Hicks, resigned his position, and Rath, as Pauling’s protégé, was appointed in his place. Following this, the outgoing president of LPISM, Emile Zuckerlandl, was succeeded by Pauling’s eldest son, Linus Pauling Jr. Finally Pauling, his health in decline, announced his retirement as chairman of the board and was named research director, with Steve Lawson appointed as executive officer to assist in the day-to-day management of what remained of the Institute.

One day prior to his retirement as board chairman, Pauling signed a document in which he requested that Rath carry on his “life’s work.” Linus Pauling Jr. and Steve Lawson, however, had become concerned about Rath’s role at the Institute, and particularly on the issue of a patent agreement that Rath had neglected to sign. Adhering to the patent document was a requirement for every employee at the Institute, including Linus Pauling himself. When pressed on the issue, Rath opted to resign his position, and was succeeded as vice president by Stephen Maddox, a fundraiser at LPISM.

After this transition, Pauling met with Linus Jr. to discuss the Institute’s dire straits. Pauling’s youngest son, Crellin, had also became more active with the Institute as his father’s illness progressed, in part because he had been assigned the role of executor of Pauling’s will. Together, Crellin, Linus Jr., and Steve Lawson struggled to identify a path forward for LPISM. Eventually it was decided that associating the Institute with a university, and focusing its research on orthomolecular medicine as a lasting legacy to Pauling’s work, would be the most viable avenue for keeping the Institute alive. The decision to associate the organization with Oregon State University, Pauling’s undergraduate alma mater, had not been made by the time that Pauling passed away.