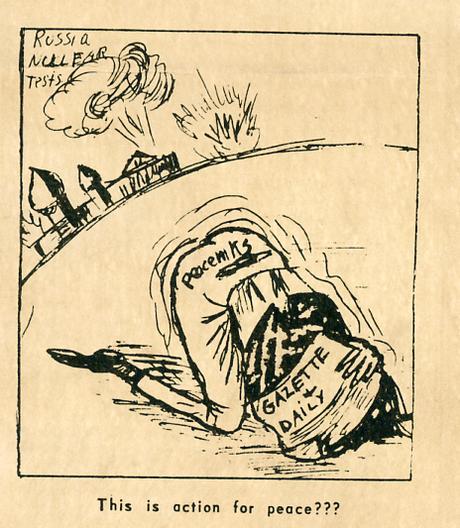

Editorial cartoon published by the Anti-Communist League of York County.

Linus Pauling’s tendency toward litigation during the 1960s has been well-documented on our blog. As a central figure in the debate over nuclear weapons testing, Pauling was considered by many to be an important advocate for world peace, while many others called him out as a subversive communist. Pauling’s reputation clearly suffered due to the negative press he received, and over the first half of the decade, he decided to combat these attacks through libel suits against conservative presses and other groups that had published defamatory articles against him.

The last three of these cases were filed against the Anti-Communist League of York County, Nevadans On Guard, and the Australian Consolidated Press. These cases all ended poorly for Pauling, a trend that defined much of his litigation. Indeed, out of eight cases that Pauling mounted, he only won two, and they were the two earliest cases.

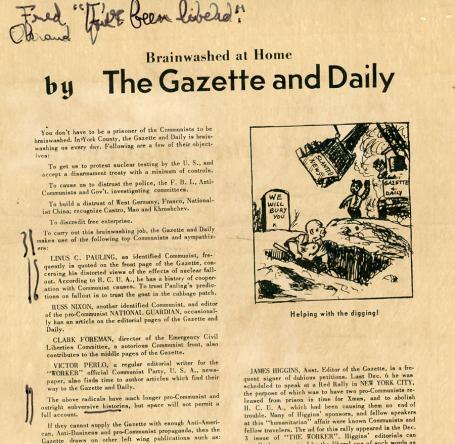

Excerpt from the Anti-Communist League of York County pamphlet that prompted legal action by Linus Pauling.

In May 1962, Charles M. Gitt, the president of the Gazette and Daily, two local York County, Pennsylvania newspapers, notified Pauling about a pamphlet that had been distributed by the Anti-Communist League of York County. The pamphlet consisted of an article titled “Brainwashed at Home by the Gazette and Daily” that theorized

To carry out this brainwashing job, the Gazette and Daily makes use of the following top Communists and sympathizers: Linus C. Pauling, an identified Communist, frequently is quoted on the front page of the Gazette, concerning his distorted views of the effects of nuclear fallout. According to H.C.U.A., he has a history of cooperation with Communist causes. To trust Pauling’s predictions on fallout is to trust the goat in the cabbage patch….The above radicals have much longer pro-Communist and outright subversive histories, but space will not permit a full account.

Pauling quickly responded to Gitt, writing “My attorney tells me that the phrase ‘an identified Communist,’ and the reference to ‘outright subversive histories’ are libelous.” Gitt agreed and encouraged Pauling to sue.

In June 1962, Pauling wrote to an area lawyer, Henry Sawyer of Philadelphia, inquiring into his willingness to serve as his counsel. In this initial letter, he put forth the gist of his complaint against the Anti-Communist League of York County.

The description of me is, in my opinion, defamatory, libelous, and grossly damaging to me. My textbooks of chemistry are used in the State of Pennsylvania and in adjacent states, and the dissemination of defamatory material of this sort may well cause me financial loss….You can understand why I feel that it is necessary for me to protect my reputation in the Philadelphia area, against an attack of this sort….I must tell you that at the present time I am involved in three libel suits, and have just brought a fourth to its termination. The one that was settled was against the Bellingham Publishing Company, Bellingham, Washington. It was settled by payment of the sum of $16,000 to my wife and me.

Pauling and Sawyer were aware that Pauling had only about a 50-50 chance of winning and, were he to win, it was likely that the damages received would be modest as the York County group was quite small and lacked significant funding. But at the time, Pauling was more interested in proving his point and casting a warning to others who might entertain the idea of publishing similarly defamatory articles. In the end, Pauling decided to sue the Anti-Communist League and its backers for $100,000, knowing that a payday of this magnitude was very unlikely to come to pass.

Once notified of Pauling’s suit, the Anti-Communist League did everything in its power to delay court proceedings as long as possible. This tactic paid off when, in 1964, a landmark Supreme Court Case, New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, was decided. The verdict handed down by the high court in this case set a stiff standard for proving libel against public figures and rendered Pauling’s case virtually unwinnable.

Though their hopes of victory were greatly reduced, Pauling and his team moved forward with the York litigation and finally received a pre-trial conference in the summer of 1965. The judge at the conference stated that the case clearly fell within the purview of the New York Times ruling, just like nearly all Pauling’s libel suits. Furthermore, none of the defendants really had any money. Ultimately, a lone defendant offered to settle for $2,000 and Pauling decided to accept the offer. Nonetheless, the damages received represented a clear loss for Pauling, as his legal fees had far exceeded $2,000 by this time. In May 1966, the case was finally dismissed in entirety.

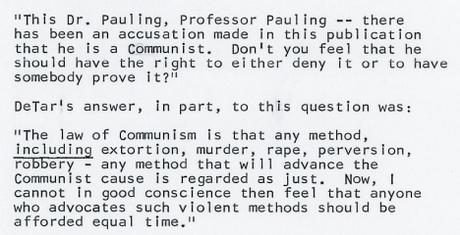

Comments by Dr. Detar, a potential defendant in the Nevadans on Guard suit.

On October 26, 1963, a small newspaper, Nevadans On Guard, published an article about Pauling bearing the headline “American Communist Given Nobel Prize.” Upon learning of this, Pauling decided to sue Nevadans On Guard, as well as the DeTar family, the Schaefer family, and possibly others responsible for defaming Pauling in the area.

In January 1964, Nevada attorney Charles Springer agreed to take on the case. The following March, Pauling lost his case against the St. Louis Globe Democrat at the same time that many of his other legal proceedings were not going as well as expected.

Charles Springer was also the State Chairman of the Democratic party in Nevada, so he was quite busy. This need to juggle obligations delayed the filing of Pauling’s suit until 1965. After that point, no additional records about the Nevadans On Guard case remain extant in Pauling’s records. One might reasonably speculate that Pauling decided against going forward with the case since he was already embroiled in so many other losing battles.

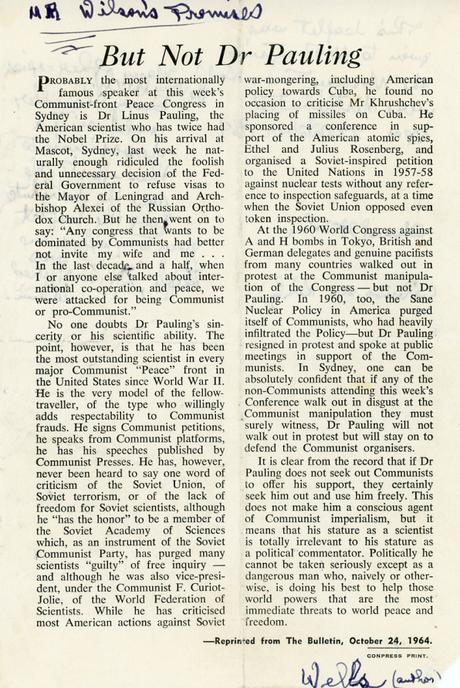

The Bulletin publication that prompted legal action in Australia.

In the Fall of 1964, the Paulings visited Australia to participate in the Australian Conference for International Cooperation and Disarmament. While in Sydney, Ava Helen Pauling was handled a leaflet excerpted from an Australian magazine, The Bulletin, that had been published on October 24, 1964. The leaflet consisted an article titled “But Not Dr. Pauling” that implied that Pauling was a liar and a communist sympathizer. After a bit of investigating, Pauling learned that The Bulletin was owned by Australian Consolidated Press, Ltd., which stood by its article and expressed no fear at the prospect of legal action.

Regardless, Pauling’s lawyers thought he had a good chance of winning until June 1965 when, in a lengthy letter, his lawyers outlined an array of pitfalls, mostly having to do with public perception. Pauling’s primary lawyer in Australia, E. J. Kirby, began by stating of the leaflet’s author

One gets the impression of a writer who is not exact or careful, and who wished to make the most biting, extravagant attack, either because he felt you would not hit back, or because he wished deliberately to provoke you to it.

From there, Kirby outlined his view of what the jury’s reactions to the case might be, detail by detail. Specifically, he felt that the jury might be influenced by the defense to think that Pauling was indeed associated with communists, simply due to the large number of Pauling’s acquaintances that would be called into question. Even if Pauling’s counsel proved that each and every one was not a communist, “Unfair as you may think it, they may come to believe that where there is so much smoke there must be some fire.”

Furthermore, though Kirby thought it likely that the jury would understand that Pauling was himself not a communist and did love the US, “we think that the jury may well be convinced, finally, just as the Senate Committee [Senate Internal Security Subcommittee] was convinced, that you have allowed yourself to be used by Communists, and Communist-front organizations, that you have been drawn into their orbit, as it were, and have to some extent become influenced by their ways of thinking.”

Kirby then pointed out that Pauling had made the deliberate decision to be more critical of the US than of the Soviet Union because he believed that it was his duty as a citizen and that he wished to serve as a model of diplomacy among nations. Though Pauling had claimed on many occasions that he did not know anything about communism or communist fronts, few juries were likely to prove overly sympathetic, given Pauling’s long history as an activist.

In view of these headwinds, Kirby advised his client that success seemed unlikely.

On the whole, therefore, we have very reluctantly come to the conclusion that what the Senate had to say in its Report, and even what the “Bulletin” had to say in its article, could be regarded by a jury as being to an extent justified in the practical sense, by the facts. In so regarding the Senate Report and the “Bulletin” article a jury, you may say, would be acting in an unjustified fashion, yet this we think is what one must do in the ordinary affairs of life, and what we believe the jury may well do in your case, however much the Judge may direct them on these points of evidence to the contrary.

Indeed, the situation looked bleak. “We now have some reservations as to the defamatory matter itself,” Kirby wrote, “[and] we have formed the view that it could well be held to be justified in part.”

A with the York County case, the issue of money emerged as an additional complication. As Kirby explained “Our Supreme Court delivered itself of a judgment in what we call the Uren case, to the effect that a plaintiff is entitled only to compensatory damages, and not to punitive or exemplary damages.” Kirby estimated that a trial would take anywhere from six to eight weeks and that the total cost to Pauling, if he lost, would amount to £10,859.10. Likewise, the total cost if he won was estimated at £954.12. Either way, Pauling stood to lose monetarily with the possible outcome of a fantastic financial loss should the case not go his way.

After reading this letter, Pauling understandably decided not to continue with the Australia case and, by September 1966, it was formally concluded.

That same year, Pauling lost his appeal in the St. Louis Globe Democrat case. Pauling’s final libel suit, bitterly contested against the National Review, took two more years to conclude, and it too ended in defeat for Pauling. Hampered by a Supreme Court decision that came about in the midst of his most litigious period, Pauling’s legal war against the press cost him a great deal personally and monetarily, and won him little.

Advertisements