Linus Pauling, 1969. Credit: Margo Moore.

[An examination of Linus Pauling’s years at Stanford University. Part 2 of 7.]

Linus Pauling began his appointment as Professor of Chemistry at Stanford University on July 1, 1969. During his years in Palo Alto, Pauling’s experimental work largely focused on developing and refining urine and breath analyses for use in diagnosing various diseases and genetic conditions ranging from schizophrenia to cancer, skin disease, heart disease, and Huntington’s chorea. In addition to funding from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation, Pauling and his laboratory were supported by a collection of smaller awards including a 1971 grant from the American Schizophrenia Association.

During his Stanford years, Pauling also continued to promote his research and peace work through a hectic travel schedule and regular publications. In January 1970, Pauling served as Visiting Professor at the Technical University of Chili, where he also received the Medal of the Senate of Chili. That same year, Pauling published an influential article, “Evolution and the Need for Ascorbic Acid” as well as his book Vitamin C and the Common Cold. The latter would become a bestseller.

In 1971 Pauling published six articles, one on nuclear weapons and others covering various topics in chemistry. He also completed revisions for, and saw published, the third edition of his hugely successful textbook, General Chemistry. In April 1971, he received the Lenin International Peace Prize at the Soviet Embassy in Washington, D.C. The next year, he partnered with Paul Wolf in the Department of Pathology to study sickle cell anemia. And in early 1973, Orthomolecular Psychiatry was published, which Pauling co-edited with David Hawkins. In short, though now in his early 70s, it was clear that Pauling had no intention of slowing down.

Not long after his arrival, Pauling identified a need to begin situating himself within the university’s administrative apparatus. One of the first items on his to-do list was to update his consent forms and put them on Stanford letterhead. Since he was now associated the university, doing so would help should any legal problems arise with his research.

As part of this process, Pauling also had to make sure that his experimental designs were in accordance with Stanford’s standards by running them by the university’s Committee on the Use of Human Subjects in Research. This process included, for one, clarifying whether or not the dose of Vitamin-B6 used in a particular study “approach[ed] the 4 GM/Kg that produces convulsions and death in animals.”

Perhaps most importantly, though he fully understood the modest circumstances governing his hire at Stanford, Pauling was nonetheless perturbed at times with the accommodations that had been made for him. In an undated letter to Alan Grundmann, a that time an assistant to the Stanford provost, Pauling complained about his small work area, emphasizing that space around him was sitting unused. As his mood soured, Pauling demanded that Stanford do a better job of acting in accordance with the space guarantees that had been stipulated in his contract. Pauling subsequently threatened to leave if the situation didn’t improve, suggesting that he might return to the University of California in San Diego, where he knew that they had enough space for him.

Though his relationship with administration may not have been perfect, other faculty members at Stanford were clearly very interested in Pauling’s research and teaching. Not long after he arrived, a variety of professors began asking Pauling to address classes varying from a general chemistry course, a psychiatry research seminar, and a postgraduate survey of basic medical science. Pauling also spoke to medical and psychiatry students about vitamin C and his newly developing concept of orthomolecular medicine.

Pauling’s understanding of social issues also proved to be a draw for his colleagues. In one instance, he and Ava Helen jointly addressed a freshman seminar on the social responsibility of scientists. Pauling also participated in Stanford’s Professional Journalism Fellowship Program series, at which he was asked to respond to the question, “What would you do if you were Secretary of State?”

Even Pauling’s personal medical examinations piqued interest within the Stanford community. Roy H. Maffly at the Department of Medicine conducted a renal evaluation of Pauling, a study that was possibly inspired by Pauling’s successful bout with glomerulonephritis in the 1940s. (a medical triumph that had been led by a Stanford physician, Thomas Addis) Maffly was also keen to learn more about Pauling’s own urine studies and agreed to interpret the results of Pauling’s evaluation using Pauling’s methods.

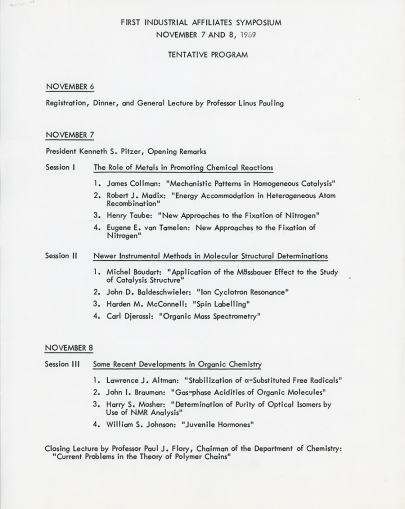

Within the Chemistry Department, Pauling joined the Industrial Affiliates Committee, which was chaired by his friend Carl Djerassi. This committee sought to connect private corporations to the research being conducted within the Chemistry Department by addressing questions like the relationship between chemistry and chemical engineering. Pauling was also involved in organizing different symposia for the committee, speaking at its first such gathering in November 1969. He likewise represented the group when he presented on his vitamin C research at an international conference in 1973.

Pauling further integrated himself into the Chemistry Department by taking on graduate students. By the start of his second year, Pauling was chairing two doctoral committees and was a member of four others. His students included Robert Copland Dunbar, who was using ion cyclotron resonance to study the interactions between ions and molecules. Margaret Blethen and John Blethen, both of whom worked with Pauling on his schizophrenia studies, and David Partridge, who worked on the chromatographic analysis of urine samples, were also mentees of Pauling’s.

Working with doctoral students gave Pauling the opportunity to offer advice based on his experiences at the University of California San Diego, where graduate students rotated between different laboratories during their initial months. Pauling suggested to others in the Chemistry Department that first year students rotate through six different laboratories, spending six-week periods in each over the course of the year. Pauling believed this to be an effective way for new students to get to know staff and to better understand the different lines of research being conducted. Armed with these experiences, the students would then be better able to make a considered decision when it came time to choose the path that they would follow at the start of their second year. Pauling also suggested that graduate student research not be tied to funding.

Advertisements