[This is the first installation of a seven-part series examining Linus Pauling’s years at, and associations with, Stanford University.]

Long before arriving at Stanford University as a professor, Linus Pauling had built a working relationship with the Stanford Research Institute through its branch office in Los Angeles. In February 1950, Pauling agreed to join the branch’s advisory panel on atmospheric pollution. Pauling’s role on the panel, according to J. E. Hobson, the director of the Stanford Research Institute, was to give “scientific and technical assistance in connection with our air pollution activities and, particularly, assistance regarding the solution of the Los Angeles smog problem.” The panel was to meet monthly at the University Club in Los Angeles over a period of six to eight months. Pauling would be paid a $100 consulting fee for each meeting.

The panel’s gatherings typically centered around a specific topic like ozone, the chemistry of hydrocarbons, or the future of research. One other meeting consisted of a tour of the laboratory at the Pasadena Field Office. After making this visit in July 1950, Pauling offered suggestions for improving the air cleaning technologies that were under development there. Specifically, Pauling suggested to A. M. Zarem, director of the Los Angeles Laboratory of the Stanford Research Institute, that “an effort be made to fractionate the oxidant in smog by the use of a variant of chromatographic adsorption.”

Unable to recall the names of those who had previously done similar research, Pauling provided his own suggestions on the best way to clean smog-filled air. Pauling’s method first advised that water vapor be removed from a tube containing activated alumina and liquid air. Having done so, Pauling then suggested increasing the temperature of the system such that a small amount of smog-free air or nitrogen could be passed through the tube, in the process collecting the pollutants. Zarem liked Pauling’s idea and wanted to develop and test it.

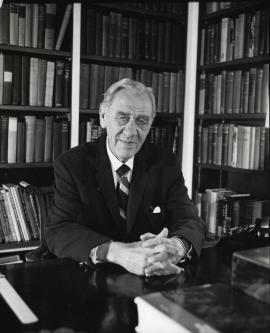

Stanford President J. E. Wallace Sterling. Photo credit: Leo Holub.

A decade later, in early 1961, the smog in the Los Angeles area had gotten so bad that it led Pauling to consider moving away, possibly to Stanford University. In addition to its pristine reputation as a world-class university, Stanford was also attractive due to its relative proximity to Pauling’s ranch at Big Sur. The end of his academic career was also on Pauling’s mind, as he would be reaching Caltech’s mandatory retirement age in eight years. At Stanford, on the other hand, he would have an extra two years available to him.

As his thinking progressed, Pauling decided that he would most like to join Stanford’s Hopkins Marine Station as their Professor of Molecular Biology, ideally working under a five-year appointment. Lawrence Blinks, who worked at Hopkins, offered Pauling an office in the station’s library and a possible laboratory space on Canary Row.

Before he went up to visit Blinks and Stanford President J. E. Wallace Sterling, Pauling sent a letter assuring Sterling that he would not impose any financial burden on the university since he was able to secure much of his own funding. Pauling’s recent grants had been used to support an eclectic program of work, including his development of a molecular theory of general anesthesia and new inquiries into the potential chemical basis of mental illness. During his visit however, Pauling discovered that a laboratory space would not be available at all and that he would not have access to office space during the summer.

After the visit had been completed, President Sterling followed up, writing that the ideal arrangement that Pauling had put forth was impracticable and would not work. Undaunted, Pauling replied that, even if he did not have access to laboratory space, he would still view working at Stanford as a step in the right direction. In his letter to Sterling, Pauling made his case:

I have thought about the nature of my contributions to science, and have recognized that the important ones are the result of my theoretical work rather than of my experimental work, although the theoretical ideas have sometimes been verified in a valuable way by the experimental work… Moreover, I have got rather tired of supervising experimental work, and have decided that I want to devote my time instead to theoretical work. In particular, I do not want to administer a laboratory.

Despite this concession on laboratory space, the ability to financially support himself, and his evident usefulness to Hopkins as the study of biology shifted more and more towards a molecular focus, Pauling’s request for a five-year professorship was still too much for Sterling to accept. Thus rejected, Pauling would have to wait almost another decade before his desire to be at Stanford was fulfilled.

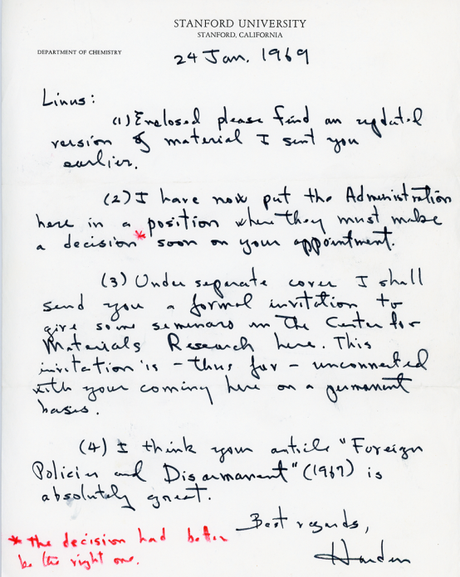

Letter from Harden McConnell to Pauling, January 24, 1969.

At the end of 1968, now five years removed from Caltech, Pauling made contact with Harden McConnell, a professor in Stanford’s chemistry department, and renewed the conversation about his potential move to Palo Alto. McConnell replied that “everyone is enthusiastic” about the possibility that Pauling might join the department.

Despite this, Pauling soon found that he was facing hurdles similar to those he had encountered in 1961. Once again, Pauling went out of his way to emphasize that he would not impose any financial burden on the university and could pay much of his own salary through grants that he had won. At the end of January 1969, McConnell wrote to Pauling with an update, “I have now put the Administration here in a position where they must make a decision soon on your appointment.” Annotating the letter in red ink, McConnell added: “The decision had better be the right one.” Within a few weeks, a verdict was rendered and Pauling was in.

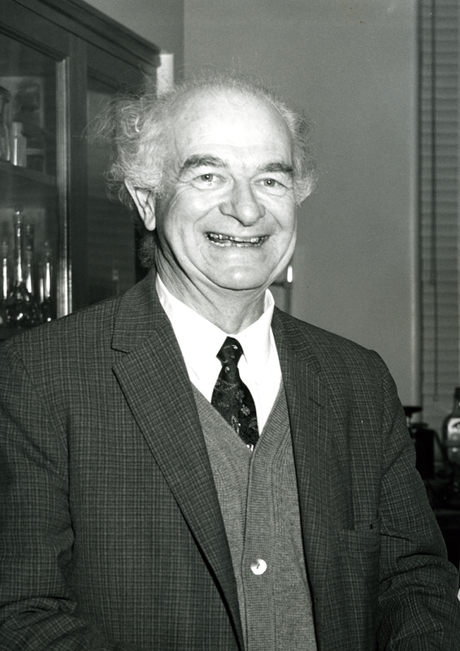

Linus Pauling, 1969. Photo credit: Ralph Shafer.

Even after he had been accepted, Pauling was made to understand that his future at Stanford was not fully assured and that he would have to follow through on his claims of self-support. For his part, McConnell could only promise that the chemistry department would cover half of Pauling’s salary for the first year. Beyond that, there was no certainty about what future years might look like. In relaying these details, McConnell lamented that, “The Chemistry Department is unanimously in favor of your coming here, and we are all greatly disappointed that the material aspects of the arrangements are so meager.” All the same, by March Pauling had been approved for a one-year appointment that would begin in July 1969.

Unlike his previous attempt to come aboard at Stanford, Pauling was this time given his own laboratory. Located in the Chemical Engineering building, the space was offered for up to three years, were Pauling to stick around that long. Jumping at this opportunity, Pauling began organizing the move of his laboratory infrastructure from San Diego to Stanford, enlisting his former student, Art Robinson – now a professor at UC-San Diego – to head up the operation. In addition to Robinson, post-doc Ian Keaveny and lab technician Sue Oxley also followed Pauling up from southern California. James McKerrow, who had sought out Pauling while he was at UCSD, likewise joined the laboratory as a research assistant.

Shortly after Pauling had completed the move to Palo Alto, he began making himself a part of the Stanford community by donating many of his scientific journals to the university. The community also reached out to Pauling, beginning with faculty in the sciences who began inviting him to participate in various department-sponsored functions. Physics professor Alexander L. Fetter, for one, asked Pauling to join a panel at an upcoming Conference on the Science of Superconductivity. So too did chemist Carl Djerassi enlist Pauling’s participation in a symposium sponsored by the department’s Industrial Affiliates Program.

Ultimately Pauling was forced to turn both of these opportunities down because he was already committed to participating in a Nobel conference and a talk at the Symposium on Sulfide Minerals in New Jersey. As we will see, many other opportunities to participate in all manner of faculty functions arose over the coming years at Stanford.

Advertisements