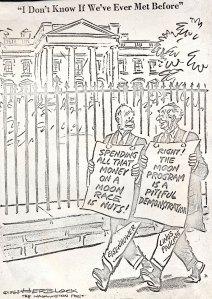

Herblock editorial cartoon published in the Washington Post, November 1963.

[Post 2 of 2 marking the centenary of Jerome Wiesner’s birth]

When Linus Pauling traveled to Norway to receive the Nobel Peace Prize in December 1963, he stepped off the plane and was filled with indignance. At first he couldn’t be sure, but after a few minutes it was clear: contrary to well-established convention, no representative of the U.S. government had arranged to meet him at the airport.

Pauling participated in the ceremonies as scheduled, but he did not forget this slight. On December 13th, two days after he delivered his Nobel lecture, Pauling wrote to his friend, Jerome Wiesner

The Nobel Ceremonies were fine. They were marred only by the boycott by the American Embassy. Usually the ambassador of the country of the Laureate is at the airport to greet him, at the prize ceremony, at the banquet, and at the Nobel Lecture. Day before yesterday Director Gunnar Jahn, the chairman of the Nobel Committee of the Norwegian Parliament, told me that a member of the U.S. Embassy staff had come to see him (about another matter), and that he (Jahn) had said, ‘You go back and tell your Ambassador that his behavior this year has been an affront to the Norwegian Nobel Committee.’

Wiesner had just concluded a three-year stint as Chairman of the President’s Committee on Scientific Affairs (PSAC) and Pauling thought that Wiesner might possibly have access to information about the government’s failure to acknowledge Pauling’s prize.

Wiesner, however, could only offer a guess that the government officials were too busy with other affairs to greet Pauling at the airport, a notion that Pauling had already dismissed out of hand. Rather, Pauling was convinced that the embassy simply chose not to acknowledge his efforts to promote world peace because these activities often led him to denounce the government’s projects and ambitions.

North Mankato (Minnesota) Free Press, May 6, 1963.

Regardless of the justifications that Pauling was given regarding this incident, it is interesting to note that he had a friend in the White House during some of the most tumultuous years of his public life. The year 1963 was one during which Pauling both received perhaps the highest-profile award that an individual can receive – the Nobel Peace Prize – and also decided to end his tenure of over four decades at Caltech, all due to resistance to his political views and activism.

And while he was recognized around the world as an outspoken critic of nuclear weapons testing and proliferation, Pauling also made headlines in 1963 for a reason that is less well-known to most: his failure to support space exploration. It is thus ironic that one of the few people who agreed with him was precisely Jerome Wiesner, a high-level advisor serving in the White House that Pauling so commonly criticized.

Indeed, Wiesner and Pauling’s friendship was centered on policy issues of mutual interest; despite the fact that each lived on opposite sides of the country, they kept in contact primarily through sharing ideas on nuclear weaponry and space exploration. Both Pauling and Wiesner believed the two issues to be of paramount importance. And while each man had slightly different reasons for taking this shared position, both also strongly believed that the federal government needed to change course.

One of Jerome Wiesner’s core beliefs was that the national government should place an emphasis on providing a robust funding infrastructure – post-graduate fellowships, for instance – for scientific minds to pursue their own research agendas as they progressed through their careers. Doing so, Wiesner felt, would secure the importance of scientific endeavors and technological advances in the United States.

Pauling agreed with Wiesner’s position, but as an activist not formally affiliated with the government, he was much more free to parse the details of where the money was going. He could see, for example, that there were benefits to be gained by exploring outer space and developing nuclear technologies, but he was very uncomfortable with the fact that these technologies would being developed for use in war. Likewise, he took issue with the fact that the federal government continued to spend money on weapons that put the public at further risk, when that same money could be used to fund research that, in his view, would improve quality of life for many.

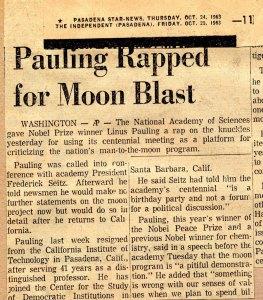

In October 1963, news reporters across the country published articles describing one of Pauling’s more public declarations of opposition to the U.S. space program. During a lecture commemorating the National Academy of Sciences’ 100th anniversary, Pauling stated that “Something is wrong with our system of values when we plan to spend billions of dollars for national prestige.”

Pauling’s comment referred to the common understanding that a driving force behind American space exploration was a perceived need to match and surpass the Soviet Union’s achievements. In this, Pauling expressed agreement with Wiesner’s own criticisms of the moonshot efforts. Both believed that the moon project alone was absorbing too much money and that, although useful, these efforts would not provide the same volume of proportional benefits that other forms of scientific research could.

Pauling couched his criticism of the space program by emphasizing his opinion that the U.S. government needed to reject the perceived need to match or stay ahead of the Soviets’ technological advances. Instead, the U.S. should focus on decreasing human suffering, a core principle of Pauling’s own belief system. Pauling’s personal interest in medicine also led him to state, perhaps hyperbolically, that it would be possible to “answer 1,000 interesting and important questions about the human body for every one question answered about the moon.” News reporters further noted that, at the National Academy of Sciences celebration, Pauling had suggested that scientists had the knowledge to combat many diseases but simply lacked the money to test their ideas.

It is both important and interesting to note that Pauling’s critique of the moonshot at the NAS celebration was actually a very small detail of his evening. In fact, Pauling’s talk, which was on chemical structure, did not mention the moon initiative at all, though he did bring it up immediately following the conclusion of his formal remarks. Nonetheless, reporters focused on the critique and rapidly disseminated Pauling’s ideas. And after his talk, Pauling was chided by NAS President Frederick Seitz, who told Pauling in a private meeting that the event was “a birthday party and not a forum for a political discussion.”

As with Wiesner before him, Pauling’s stance on the moon project was met with significant criticism. And, of course, the U.S. did continue to move forward with the project, famously landing an astronaut on the moon’s surface in July 1969. Their criticisms of the space program proved to be another instance in which Wiesner and Pauling were forced to accept the government’s decisions. But this disappointment did not stanch either man’s desire to make their ideas known as both pursued public platforms for their activism for the remainder of their lives.