[Part 2 of 2]

Linus Pauling's relationship with the scientist and peace activist Andrei Sakharov - a kindred spirit whom he never met - began in unusual fashion. In 1978 Pauling was in Moscow attending the International Conference on Biochemistry and Molecular Biology when an unidentified man handed him a letter written in Russian. As Pauling later recounted, the man, "who spoke with a pronounced Central European accent," said that the letter was from Andrei Sakharov, and that Pauling "should have it translated by some reliable person."

Pauling accepted the letter and, about a month later, had it translated by Sakharov's son-in-law, Efrem Yankelevich, a US-based activist in his own right who helped to give Sakharov a "voice" to the world during his years in exile.

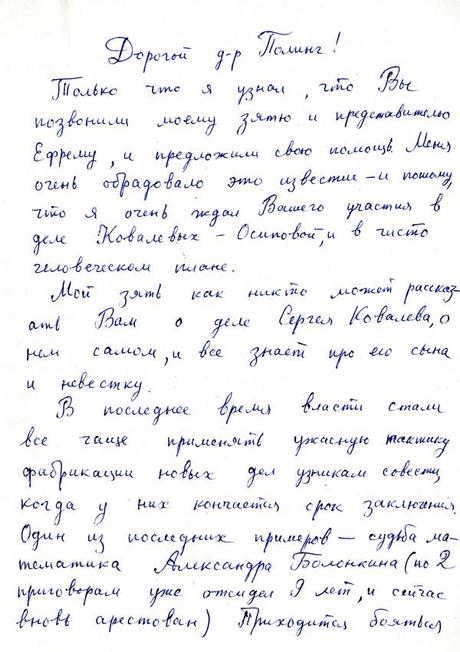

Page 1 of Sakharov's handwritten letter to Pauling, 1978

Page 1 of Sakharov's handwritten letter to Pauling, 1978 But before Pauling could get the letter translated, Sakharov sent it to several news agencies for wider distribution. In it, Sakharov asked for Pauling's support in the push to help free three Soviet scientists - physicist Yuri Orlov, mathematician Alexander Bolonkin, and biologist Sergei Kovalev - all of whom had been sentenced to terms in labor camps for acts of political dissidence.

Unfortunately, in addition to the original text, the published letter admonished Pauling for a perceived lack of action, and a claim that he was ignoring Sakharov's plea for support. In actual fact, Pauling had been traveling when the letter was published and hadn't even received a copy of the translation by the time of the letter's release. Understandably, he was frustrated for having been called out by Sakharov in this way.

Wishing to set the record straight, Pauling penned an editorial for publication in Physics Today, which was already planning to run an article on Pauling's receipt of the Lomonosov Gold Medal. In a note appended to the editorial, Pauling stressed that "no changes be made in my letter, unless I have given approval. This is a delicate matter."

The piece was published, without changes, in the magazine's December 1978 issue. In it, Pauling confessed that he felt duped and bombarded by Sakharov's tactics and chided that "in the future he should be more careful in his selection of advisors and agents."

That said, Pauling also took pains to make clear that he supported Sakharov's activist work and noted that, in the past, he had written letters in support of Soviet scientists who had been wrongly imprisoned. Nonetheless, in this particular instance Pauling did not follow through on Sakharov's request, choosing not to write letters asking for the release of the three scientists in question.

Time moved forward but Sakharov refused to let the issue fade. Two years later, in 1981, he sent several letters - including a handwritten message handed to Pauling via his son-in-law, Yankelevich - repeating the same urgent call to action in support of the three Soviet scientists. Some of these letters even included personal statements from the scientists themselves, and Yankelevich appears to have added updates on their lives. For Sergei Kovalev, the situation appeared to be deteriorating rapidly as he was reportedly suffering from tuberculosis as well as partial paralysis.

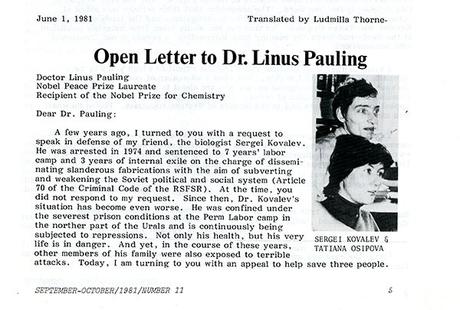

In addition to the personal handwritten notes, Sakharov once again published a separate public letter to Pauling, which appeared in translated form in the now defunct Freedom Appeals magazine. In this instance, Sakharov sought to enlist Pauling's support for the release of biologist Sergei Kovalev and his daughter-in-law, Tatiana Osipova.

While Sakharov's initial correspondence had been fairly dry, this latest published letter was more emotional. Addressing Pauling, Sakharov wrote,

I know neither your political views nor the extent to which you may be sympathetic to the Soviet regime. But what I am asking of you is not politics. To save honest and courageous people who are about to perish is the duty of humaneness and a question of honor. Please make good use of your prestige; appeal to Soviet leaders and to the leaders of Western countries. Please do what you can.

This new approach seems to have made an impact, if in an oblique way. Even though Pauling once again did not act to free the imprisoned Soviet scientists - Sergei Kovalev was eventually released by Mikhail Gorbachev in 1986 - he did eventually come to the aid of a different Soviet intellectual: Andrei Sakharov himself.

Gerhard Herzberg

Gerhard Herzberg In 1980, just five years removed from his receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize, Sakharov was sent into exile in the city of Gorky, and was routinely subjected to harassment and isolation in the years that followed. In April 1981, Pauling and Gerhard Herzberg, a fellow Nobel Chemistry laureate, sent a letter to Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev and the Canadian Ambassador to the Soviet Union demanding the "end of [Sakharov's] confinement." In the message, Pauling and Herzberg explained that their letter was not a publicity stunt, and that there would be "no communication about it to the 'media.'"

Instead the authors put forth that, "every society needs its critics if it is to diagnose successfully and overcome its problems [...] Surely your nation is mighty enough to tolerate a patriotic critic of the stature of Andrei Sakharov." Pauling and Herzberg concluded by harkening back to the dark years of gulags and secret police, exhorting to Brezhnev that "Surely you do not want a return to Stalinism."

Later in 1981, after having been in exile for a year, Sakharov began a hunger strike to demand that his daughter-in-law, Liza, be permitted to move to the U.S. to be with her husband, Sakharov's son Alexei. As he initiated this protest, Sakharov sent a letter to his foreign colleagues rallying them for support. Though this plea was of a personal nature, Sakharov explained that

I consider the defense of our children just as rightful as the defense of other victims of injustice, but in this case it is precisely me and my public activities which have been the cause of human suffering.

In addition to the open letter, which was broad and impersonally written, Sakharov sent a direct message to Pauling, imploring him specifically to support the release of his daughter-in-law. Ultimately the campaign worked, and before the year had concluded Liza was granted an exit visa to live in the United States.

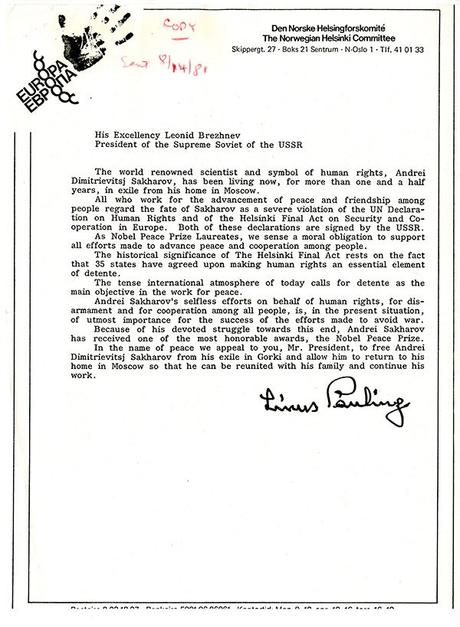

But the victory did not come without a cost. Namely, as a penalty for having gone on the hunger strike, Sakharov was stripped of all his accolades by the Soviet government. In reaction to this, an international campaign, initated by the Norwegian Helsinki Committee - a non-governmental organization dedicated to insuring that human rights are respected and practiced worldwide - solicited prominent scientists to urge Premier Brezhnev to release Sakharov from exile and allow him to return to his home in Moscow.

Pauling's letter to Leonid Brezhnev, August 1981

Pauling's letter to Leonid Brezhnev, August 1981 Pauling, clearly aware of Sakharov's plight, agreed to write a second letter to Brezhnev, and promptly sent the appeal arguing for Sakharov's release on the grounds of human rights violations. Delivered in August 1981, the letter apparently fell on deaf ears.

By 1983 Sakharov had been in exile for three years and his health was beginning to decline. Pauling's earlier attempts to secure his release had not worked, so he adopted new tactics. In mid-1983, Pauling sent a telegram to the Soviet Academy of Sciences and to then Soviet premier, Yuri Andropov, offering Sakharov a job as a research associate in theoretical physics at the Linus Pauling Institute of Science and Medicine in Palo Alto. Justifying this offer, Pauling told news reporters that "I feel sympathy for Sakharov as a person who gets into trouble for criticizing his own country." Upon learning of the offer, Sakharov publicly announced that he was willing to emigrate, but the Soviets declined to grant Sakharov an exit visa, citing "state secrets" connected to his scientific work on the hydrogen bomb during World War II.

In 1986 Sakharov was finally released amidst the Gorbachev regime's policies of glasnost and perestroika. The famed scientist and activist promptly returned to Moscow, and in 1989 he died in his home. While it seems that Pauling's attempts to free Sakharov did not ultimately work, and there is no documentary evidence that their relationship advanced in the years following his release, it is worth mentioning that Pauling received an advance copy of Sakharov's memoirs prior to their posthumous publication in 1990. It is not clear if Pauling requested the copy, but his receipt of the volume is a suggestion that, even in death, Sakharov remained with Pauling.

Filed under: Colleagues of Pauling, Peace Activism | Tagged: Andrei Sakharov, Linus Pauling, USSR |